First find in the U.S. of jeilongvirus, which can rarely cause serious illness.

A cat’s routine prey retrieval in Gainesville, Florida, unveiled a new virus, the Gainesville rodent jeilong virus 1, at the University of Florida. This virus, capable of affecting multiple species, represents a potential public health concern, underscoring the importance of ongoing wildlife surveillance and viral research.

Viral Investigation at the University of Florida

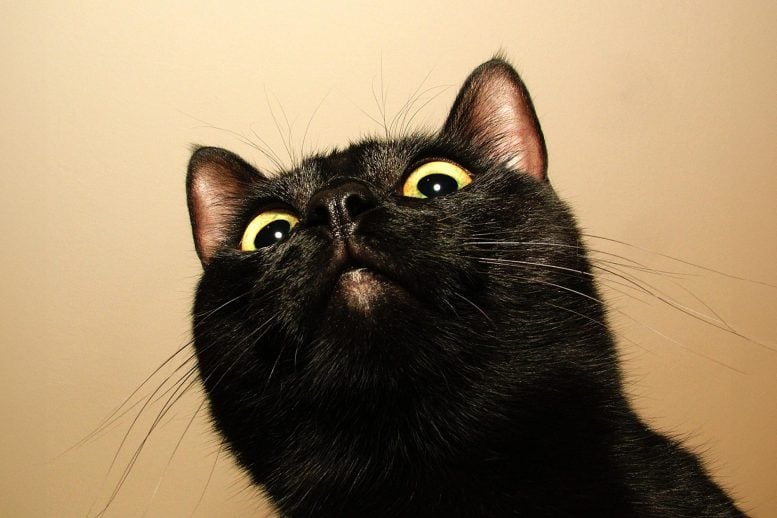

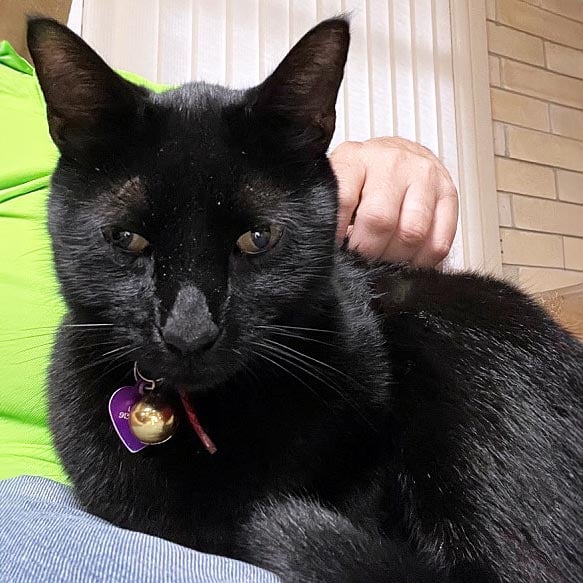

On a warm May day in Gainesville, Florida, an all-black domestic shorthair cat named Pepper strolled into his home and dropped a dead mouse on the carpet at his owner’s feet.

For Pepper, this was business as usual—he’s a practiced hunter who often leaves “gifts” for his humans. But his owner, John Lednicky, Ph.D., saw the situation differently. Lednicky, a virologist specializing in cross-species virus transmission, suspected the mouse might carry mule deerpox. Without hesitation, he collected Pepper’s prize and took it to his lab at the University of Florida for testing.

There, Lednicky and his team found that the mouse, a common cotton mouse, did not have deerpox virus. Instead, it carried a jeilongvirus, a type of virus previously identified in Africa, Asia, Europe, and South America. Part of a family of viruses that infect a range of species—including mammals, reptiles, birds, and fish—jeilongviruses have been known to occasionally cause serious illness in humans.

A New Virus Emerges

This particular strain, however, was unique. According to Lednicky, its genetic makeup is distinctly different from that of any other jeilongvirus seen before.

“It grows equally well in rodent, human, and nonhuman primate (monkey) cells, making it a great candidate for a spillover event,” said Lednicky, a research professor in the UF College of Public Health and Health Professions Department of Environmental and Global Health and a member of UF’s Emerging Pathogens Institute. A spillover event is when a virus moves from one species to another.

Implications of the New Jeilongvirus

The virus, named Gainesville rodent jeilong virus 1 by the team, is the first jeilongvirus to be discovered in the U.S.

“We were not anticipating a virus of this sort, and the discovery reflects the realization that many viruses that we don’t know about circulate in animals that live in close proximity to humans. And indeed, were we to look, many more would be discovered,” said Emily DeRuyter, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Environmental and Global Health who specializes in One Health. She is also a Lednicky mentee and first author of the paper describing the virus’s discovery that appears in the journal Pathogens.

The Research and Its Significance

Jeilongviruses are not yet well understood, but they are a type of paramyxovirus, which are associated with respiratory infections. While the finding that Gainesville rodent jeilong virus 1 can infect many different species is troubling, DeRuyter said, there is no need to panic. Most humans have little direct contact with jeilongviruses’ main host, wild rats and mice. Take for example, hantavirus, another virus found in wild rodents.

“Humans can develop severe to fatal illness if they get infected by hantaviruses, but so far, those types of infections remain rare and typically occur only among people who come into contact with rodent waste, often through airborne exposure to rodent urine or fecal material,” DeRuyter said.

Future Directions in Viral Research

The UF team was able to grow the jeilongvirus in the lab, allowing them to continue to examine the virus’s traits, said Lednicky, the study’s senior author.

“Ideally, animal studies would be done to determine whether the virus causes illness in rodents and other small animals,” he said. “Eventually, we need to determine if it has affected humans in Gainesville and the rest of Florida.”

Continuing Surveillance and Research Needs

Surveillance initiatives that identify emerging or re-emerging viral pathogens circulating within the environment or in wildlife or individuals who are high risk are also important, DeRuyter said.

“This helps to set up infrastructure to evaluate the risk of novel pathogens or determine if the virus phenotypes are shifting to become more dangerous to their hosts,” DeRuyter said.

As for Pepper, he developed no symptoms from his exposure to the virus-carrying mouse.

“Cats, in general, evolved to eat rodents, and are not sickened by the viruses carried by rodents,” Lednicky said, “but we have to do tests to see whether the virus affects pets, and humans.”

Reference: “A Novel Jeilongvirus from Florida, USA, Has a Broad Host Cell Tropism Including Human and Non-Human Primate Cells” by Emily DeRuyter, Kuttichantran Subramaniam, Samantha M. Wisely, J. Glenn Morris and John A. Lednicky, 25 September 2024, Pathogens.

DOI: 10.3390/pathogens13100831