An analysis by Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, Germany, on the manual capabilities of early hominins reveals that some Australopithecus species exhibited hand use similar to modern humans.

In demonstrating that certain Australopithecus species possessed hand anatomies conducive to tool use, the study suggests that tool use may have originated much earlier than previously documented.

The comparison study, “Humanlike manual activities in Australopithecus,” published in the Journal of Human Evolution, analyzed muscle attachment sites on the hands of the three Australopithecus species: A. afarensis, A. africanus and A. sediba. Comparisons were made using modern human, Neanderthal, gorilla, chimpanzee and orangutan hands to benchmark human versus apelike hand use patterns.

According to the study, muscle attachment sites are crucial to understanding the functional use of hands through biomechanical loading. The method allows for a more profound reconstruction of habitual activities and manual behaviors, allowing us to see the effects of sustained tool use in the biomechanics of the hands and, from this, learn a great deal about how the tool might have been used.

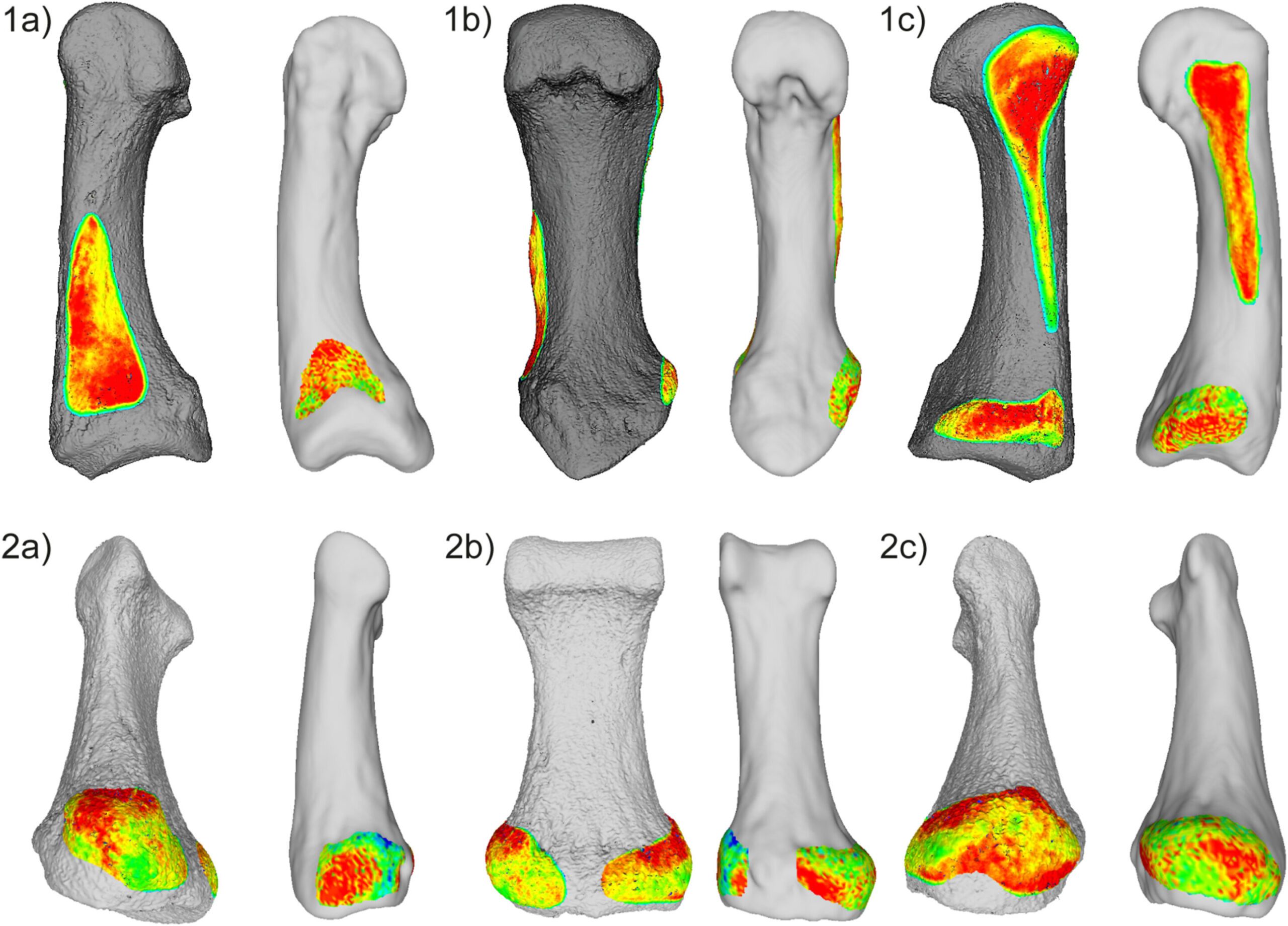

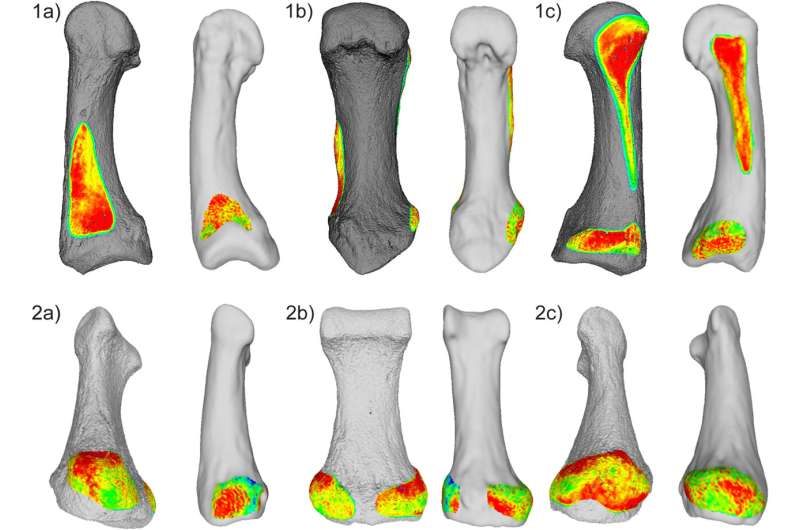

The study utilized three-dimensional models of the hand bones to investigate the biomechanics in detail. Muscle attachment areas were identified based on differences in bone surface elevation, coloration (when available), and surface complexity. The identified areas were carefully outlined to separate muscle attachment sites from the rest of the bone.

Findings indicate that A. sediba and A. afarensis possessed patterns of muscle attachment that suggest they possessed the anatomical foundation for manipulation activities similar to those of humans. This implies that these species engaged in tasks such as power grasping and in-hand object manipulation essential for tool use.

A. africanus displayed a combination of attachment features, indicating both human and apelike hand use. This mosaic pattern suggests a versatility in manual behaviors, potentially influenced by tool-related activities.

“The frequent activation of muscles needed to perform characteristic humanlike grasping and manipulation in these early hominins lends support to the notion that humanlike hand use emerged prior to, and likely influenced, the evolutionary adaptations for higher manual dexterity in later hominins,” the researchers state in their paper.

The oldest stone tools ever found date to about 3.3 million years ago, but were not found with any fossil remains that could confirm who used them. Even earlier evidence (~3.4 million years ago) of cut marks on the bones of large mammals shows that tools were being used to render meat.

Early tool makers would likely have relied heavily on bone or wooden tools, making it extremely unlikely to find traces of their existence. Still, the current study might be telling us more than artifacts alone ever could.

We may never know the full extent of the tools in the Australopithecus toolkit, but if you hold up your own hand, you will see the evidence of their use.

Overview of the three hominins studied

Australopithecus afarensis lived approximately 3.9 to 3 million years ago and was found primarily in East Africa. They were able to walk on two legs while retaining some typical tree climbing features. The braincase was on the smaller side with a prominent brow ridge and more ape-like facial features than the others. The group is well-represented by “Lucy,” one of the most complete and well-preserved A. afarensis skeletons ever discovered and possibly the world’s most famous anthropological celebrity.

Australopithecus africanus lived approximately 3.3 to 2 million years ago, primarily discovered in South Africa. Also bipedal and adapted for both walking upright and climbing, the hominins had longer arms relative to legs compared to later Homo species. The braincase was larger than A. afarensis, with a more rounded skull. They possessed smaller molars and larger canines, indicating a varied diet of tough vegetation and softer foods. They are one of the most successful hominins in terms of longevity in a persistent form (four times longer than current modern humans have been around).

Australopithecus sediba lived approximately 2 to 1.8 million years ago and were discovered in the Malapa region of South Africa. They were also bipedal and retained climbing ability. They had a slightly larger braincase than earlier Australopithecus species.

More information:

Jana Kunze et al, Humanlike manual activities in Australopithecus, Journal of Human Evolution (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2024.103591

© 2024 Science X Network

Citation:

Ancient hominins had humanlike hands, indicating earlier tool use, study reveals (2024, October 15)

retrieved 15 October 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-10-ancient-hominins-humanlike-indicating-earlier.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.