New research shows Iberian infants buried in homes mostly died from natural causes, not rituals, using advanced dental analysis techniques.

A study conducted by the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, in collaboration with the University of Vic-Central University of Catalonia and the ALBA synchrotron, concludes that newborns from the Iberian culture (8th to 1st centuries BCE) who were buried within domestic spaces died from natural causes, such as labor complications or premature births, rather than as a result of ritual practices.

Researchers applied an innovative methodology, based on the study of the neonatal line of baby teeth using optic microscopy and microfluorescence with synchrotron light, to analyze the teeth from 45 infant skeletal remains and precisely identified the moments of both birth and death.

The Iberian culture inhabited the eastern and southern coastal regions of the Iberian Peninsula during the Iron Age (8th to 1st centuries BCE). The most common funeral ritual of the Iberians was the cremation of the deceased and subsequent disposal of the remains in urns that were buried in necropolises.

However, archaeologists have also discovered burials with remains of newborns who had not been cremated, but were rather located in areas used for housing or production purposes. These burials have generated controversy among experts. Hypotheses suggested that they could have died of natural causes, be proof of infanticide, or even of ritual sacrifices.

A study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science now provides very precise evidence in favor of the hypothesis that these newborn infants died mainly from natural causes and that, therefore, are a reflection of the high infant mortality during the first year of life in the period studied.

Researchers reached this conclusion after studying 45 infant skeletal remains from five Catalan archaeological sites from the Iberian period: Camp de les Lloses (Osona), Olèrdola (Alt Penedès), Puig de Sant Andreu and Illa d’en Reixac (Baix Empordà), and Fortalesa dels Vilars d’Arbeca (Lleida).

The study was led by researchers from the Biological Anthropology Research Group (GREAB) of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) and the MECAMAT Research Group of the University of Vic-Central University of Catalonia (UVic-UCC). Also participating in the study were members of the University of Granada, the Archaeology Museum of Catalonia (MAC), the El Camp de les Lloses Interpretation Centre, the University of Lleida and the TR2Lab Research Group of UVic-UCC.

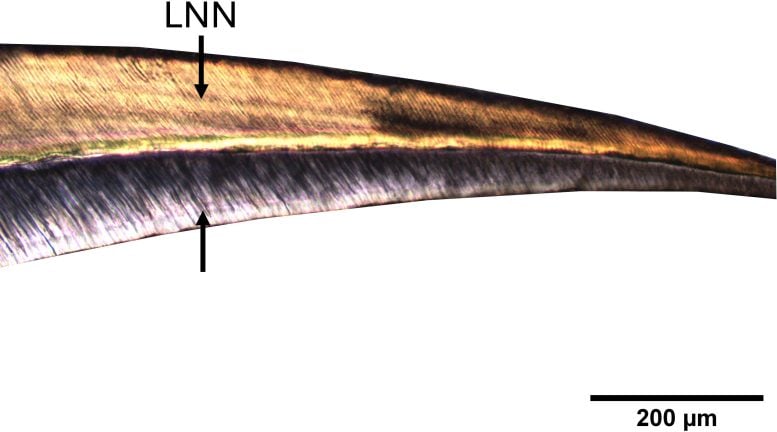

Researchers have applied an innovative methodology based on the histological and elemental analysis (tissue and chemical composition) of the deciduous or primary teeth present in the infant skeletal remains. By means of optical microscopy, researchers were able to visualize the growth lines of the dental crown generated in the formation of teeth during intrauterine life and until shortly after birth. This led them to identify the presence of the neonatal line that is produced at the moment of birth.

The analysis allowed them to identify the moment of birth of the individuals and their survival, as well as to determine very precisely the chronological age at the moment of death. The chronological age takes into account the time elapsed since birth and not the biological development of the skeleton.

Almost half of the infants died during the perinatal period, specifically between the 27th week of gestation and the first week of life. The vast majority of perinatal deaths did not survive the moment of birth, and many of these infants died due to premature births. “These data reinforce the hypothesis that the majority of perinatal deaths were caused by natural factors, such as birth complications or health problems associated with prematurity, and not by cultural practices such as infanticide or ritual sacrifice, as some hypotheses have suggested,” says Xavier Jordana, Associate Professor in the Biological Anthropology Unit of the Department of Animal Biology, Plant Biology, and Ecology at the UAB.

Researchers also observed that of the twenty or so infants that survived beyond the first week of life, the longest-lived 67 days. “In the sites studied, no burial of an infant beyond two months of life has been identified. This leads us to think that it could probably have been due to a cultural practice of burying in domestic spaces the infants who died in the earliest stages,” says Assumpció Malgosa, a researcher at the UAB and co-author of the study.

A unique technique that can specify the time of birth and death

The histological analysis researchers applied in this study is an important innovation to calculate very accurately the age of individuals at death based on the study of the crown of their teeth. Primary teeth begin to form during intrauterine life and finish forming in the postnatal stage, around birth, a period in which they register their growth due to the unique property of forming growth lines.

These lines can form on a daily basis, but thicker lines can also form due to a punctual and stressful event. One such punctual line that can be visualized with optical microscopy in the teeth of infants who have survived birth is the neonatal line, which is formed by the physiological stress caused by the abrupt change from intrauterine to extrauterine life.

“The technique we used is unique, because it allows us to identify the moment of birth and calculate the chronological age of the skeletal remains. Conventional techniques estimate the biological age of the individual based on skeletal growth and development, so they have a great variability when determining age, and do not allow us to identify the moment of birth,” says Ani Martirosyan, predoctoral researcher at the UAB and first author of the article.

The methodological innovation allowed them to differentiate the individuals who died at birth from those who were born alive and survived. Of those who died at birth, they identified those who died at full term (between the 37th and 42nd week of gestation) and those who died prematurely (before the 37th week). They were also able to determine the chronological age of the surviving infants.

Researchers confirmed the accuracy of their technique with contemporary teeth in which the chronological age of death of the individual is known. In addition, they also undertook X-ray microfluorescence from synchrotron light at the ALBA Synchrotron (Cerdanyola del Vallès), particularly at the Xaloc beamline, to analyze the elemental composition of the neonatal line, and in particular the quantification of zinc in cases where the histological visualization of the line was uncertain.

“Zinc is an important element at birth, particularly related to the onset of breastfeeding, but due to its low content, it is not possible to detect concentration variations in enamel and dentin using electron microscopy. The synchrotron light allows us to apply an X-ray beam of only 10 microns to analyze different elements in the enamel and dentin at extremely low concentrations,” says Judit Molera, a researcher at the UVIC-UCC and co-author of the research. The results of the experiment show an increase in the amount of zinc and a decrease in calcium, a main element of dental enamel, coinciding with the presence of the neonatal line, which helped researchers corroborate the histological results.

“The data from our study provide much more detailed and concrete information than we have had so far to establish the pattern of infant mortality in Iberian populations, and help to unravel important aspects of their life history and cultural practices. We trust that the methodology we applied will serve to continue to unveil other mysteries yet to be discovered about ancient populations,” concluded Xavier Jordana.

Reference: “Reconstructing infant mortality in Iberian Iron Age populations from tooth histology” by Ani Martirosyan, Carolina Sandoval-Ávila, Javier Irurita, Judith Juanhuix, Nuria Molist, Immaculada Mestres, Montserrat Durán, Natàlia Alonso, Cristina Santos, Assumpció Malgosa, Judit Molera and Xavier Jordana, 4 October 2024, Journal of Archaeological Science.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2024.106088

The study forms part of the research project entitled “Reevaluation of Infanticide and Sex Selection in the Iberian Period,” funded by the Spanish Ministry for Science and Innovation and directed by GREAB researchers.