Scientists from EMBL Heidelberg and the University of Virginia have uncovered an intriguing mechanism by which cells adapt to starvation, a discovery that could have significant implications for cancer research.

What can stressed yeast reveal about fundamental cellular processes? Quite a bit, according to researchers at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL). The team studies, among other topics, how cells adapt to stress — such as nutrient deprivation. One of their favorite test subjects is the yeast species S. pombe, for centuries used in traditional brewing. As a eukaryote, it’s in many ways similar to human cells, so biologists often use it as a model organism to study fundamental cellular processes.

Ribosomes turn upside-down in hungry cells

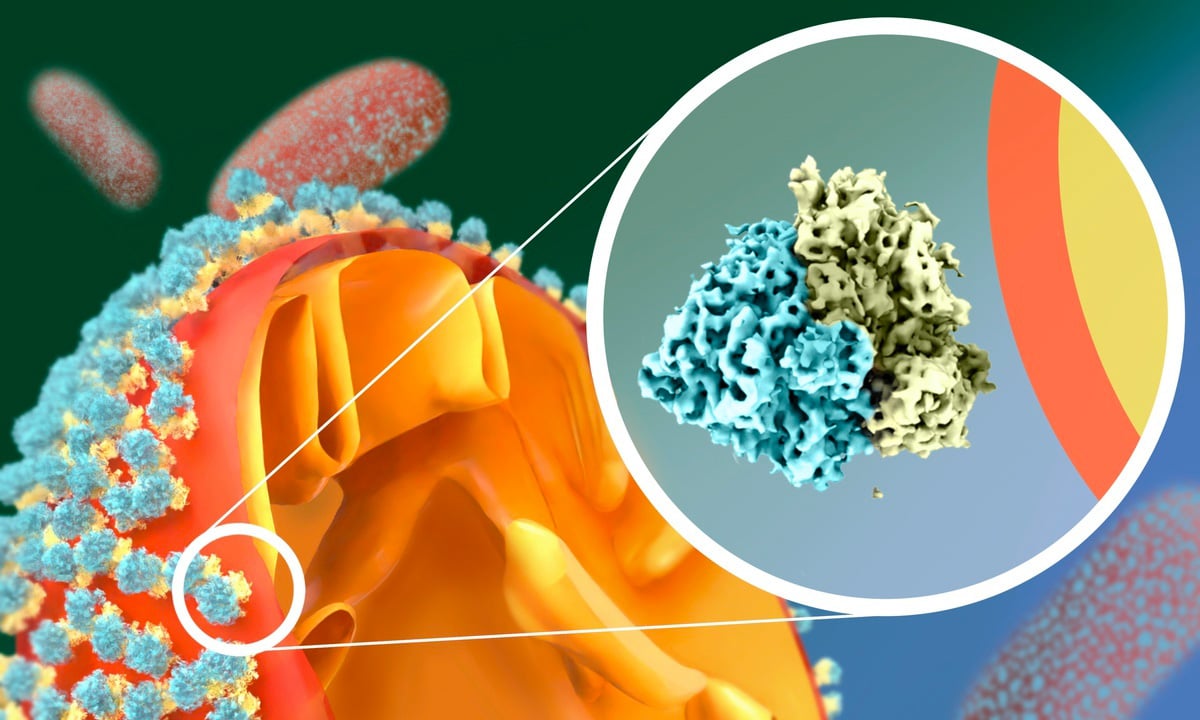

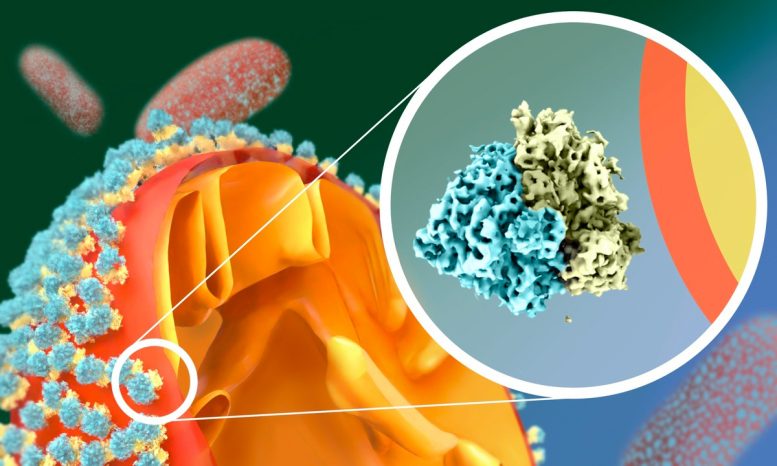

Scientists have observed that yeast cells have a remarkable adaptation to starvation: their mitochondria get coated by a swarm of massive molecular complexes called ribosomes. Intrigued by this odd phenomenon, the Mattei Team at EMBL Heidelberg and the Jomaa Lab at the University of Virginia School of Medicine explored it in greater detail using single-particle cryo-electron microscopy and cryo-electron tomography.

Ribosomes are the cell’s heavyweight molecular machinery that produces proteins. It turned out, however, that in hungry yeast cells, the ribosomes that crowd on the surface of the mitochondria don’t produce anything. They are hibernating.

“One way for a cell to survive stressful conditions until better days is to reduce its use of energy to a minimum,” explained Olivier Gemin, EIPOD Postdoctoral Fellow in the Mattei Team who led this new study. “Producing proteins demands a lot of energy, which can be saved by blocking ribosomes.”

Why the hibernating ribosomes attach to the surface of mitochondria is a mystery.

“There could be different explanations,” said Team Leader Simone Mattei. “A starved cell will eventually start digesting itself, so the ribosomes might be coating the mitochondria to protect them. They might also attach to trigger a signaling cascade inside the mitochondria.”

Another possibility that Mattei is investigating relates to the fact that starving cells need a way to quickly start producing energy once food (in the form of glucose) is available again. Since mitochondria are the energy producers of the cell, having ribosomes nearby to produce necessary proteins might help this process along.

What made the scientists’ jaws drop was noticing that the ribosomes attach to the mitochondrial outer membrane in a way that contradicts what’s been known about them before.

“So far, ribosomes were known to interact with membranes only via their large subunit. But in starved cells, we saw that they do this upside-down, via the small subunit!” said Mattei.

In their future studies, the team will investigate how and why the ribosomes attach in such an unusual way.

Cancer cells go through the hell they create

The struggles of the starved yeast cells have some similarities to those of cancer cells.

Believe it or not, being a cancer cell is really tough. When a tumor becomes aggressive, its cells grow so rapidly that their demand for nutrients and oxygen outpaces the supply. This means most cancer cells are constantly starving in a kind of hell they create for themselves.

Yet, they survive and even multiply.

“That’s why we need to understand the basics of adaptation to starvation and how these cells become dormant to stay alive and avoid death,” said Ahmad Jomaa, Assistant Professor and Group Leader at the University of Virginia’s School of Medicine and a senior co-author of the study. “For that, we use yeast first, because we can manipulate it much more easily. Beyond this, we try to starve cultured cancer cells too, which is not easy, to figure out how they overcome starvation and can sometimes lead to cancer relapse.”

Understanding the principles of this adaptation could help us find ways to override it, making cancer cells vulnerable to starvation and thus more susceptible to treatment.

Reference: “Ribosomes hibernate on mitochondria during cellular stress” by Olivier Gemin, Maciej Gluc, Higor Rosa, Michael Purdy, Moritz Niemann, Yelena Peskova, Simone Mattei and Ahmad Jomaa, 8 October 2024, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-52911-4

The study was funded by the Searle Scholars Program, the American Cancer Society, the University of Virginia, and the European Molecular Biology Laboratory.