Hurricane Milton rapidly intensified to Category 5 strength over warm gulf waters.

Hurricane Milton rapidly developed into a Category 5 storm, threatening the southeastern United States, particularly Florida. Supported by abnormally warm Gulf of Mexico waters and low vertical wind shear, Milton’s intensification was fueled significantly. Forecasts predict devastating impacts including heavy rainfall, life-threatening wind, and massive storm surges as it makes landfall near Tampa Bay.

Emerging Threat: Hurricane Milton’s Rapid Formation

As Florida and other southeastern states were grappling with the aftermath of Hurricane Helene in early October 2024, a new tropical threat emerged over the Gulf of Mexico. Hurricane Milton escalated from a tropical storm on October 5 to a Category 5 hurricane by October 7. Forecasters anticipate that Milton will make landfall late on October 9 near Tampa Bay and sweep across central Florida.

Intensification Over Warm Waters

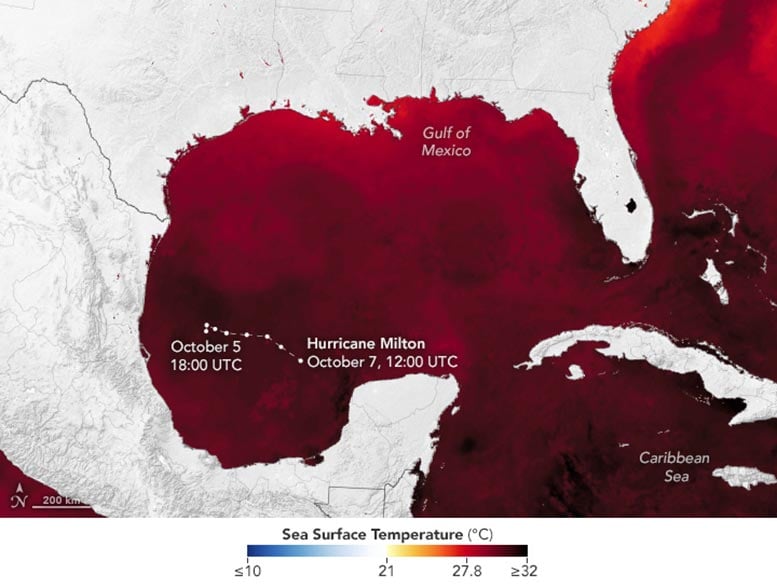

Sea surface temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico—well above average for this time of year—helped fuel the storm’s rapid intensification. Rapid intensification occurs when a tropical cyclone’s maximum sustained wind speeds increase at least 30 knots (35 miles per hour) over a 24-hour period. Milton strengthened at nearly triple that rate, with winds increasing from 80 to 175 miles per hour in 24 hours from October 6–7.

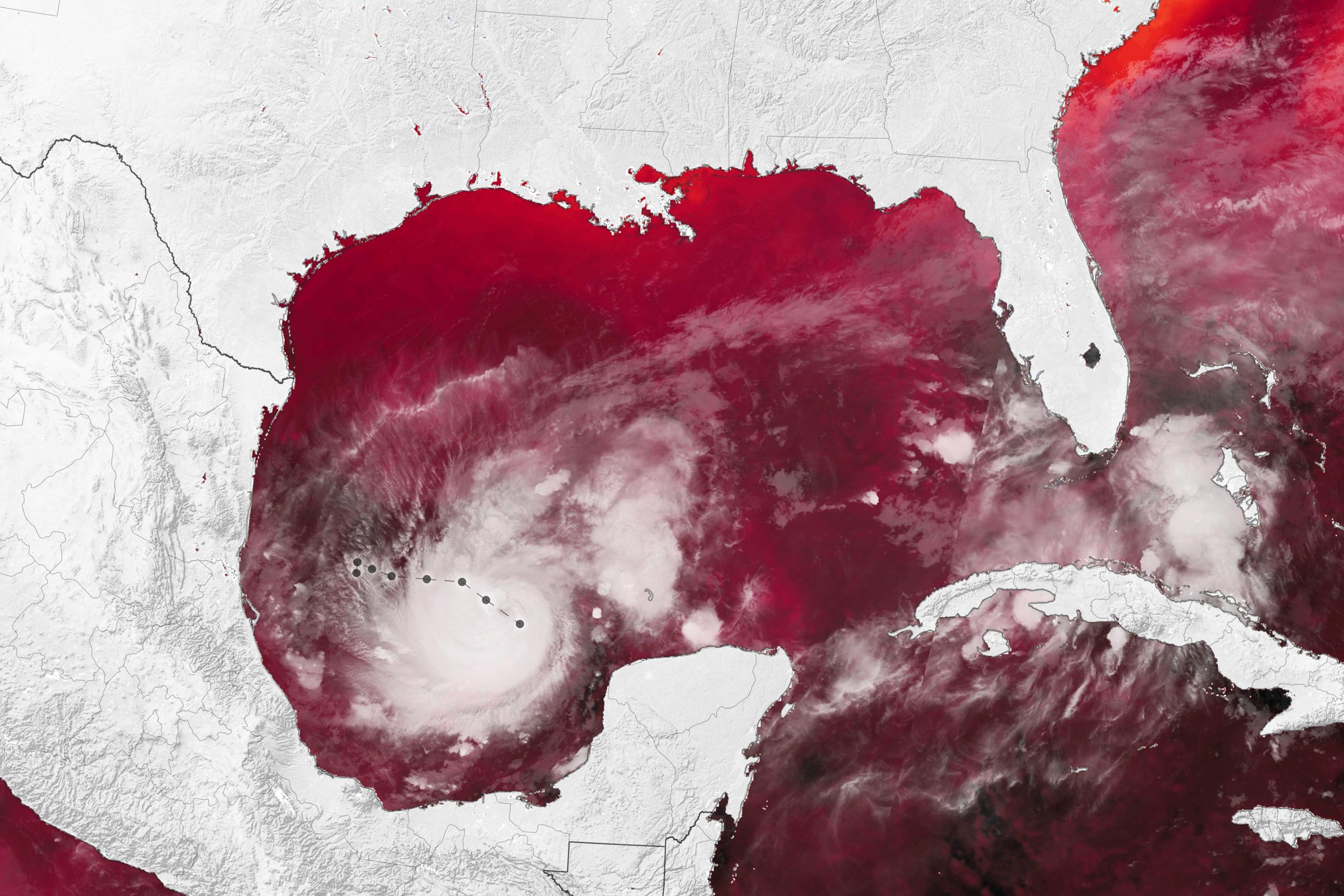

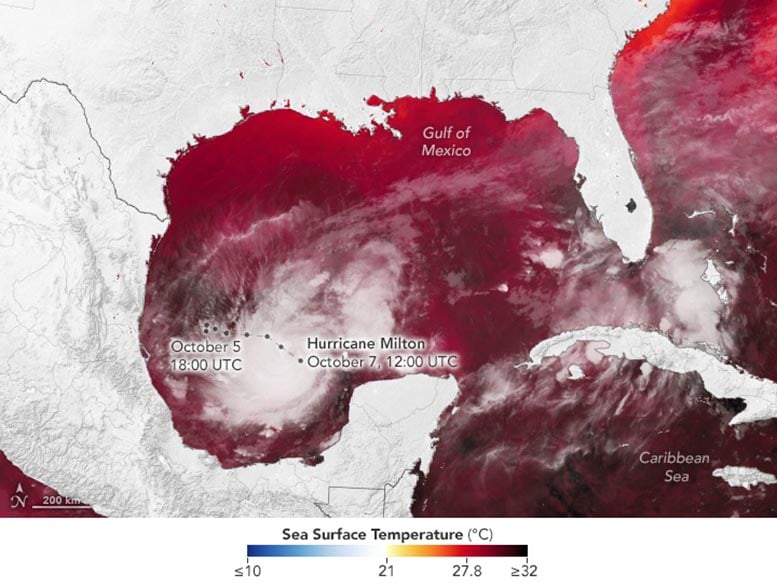

These maps show sea surface temperatures on October 6, using data from the Short-term Prediction Research and Transition (SPoRT) project based at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. Surface waters above 82 degrees Fahrenheit (27.8 degrees Celsius)—the temperature generally required to sustain and intensify hurricanes—are dark red. The map on the right is overlaid with brightness temperature data, acquired by the VIIRS (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite) on the NOAA-21 satellite in the early morning of October 7, to show the location of Milton’s storm clouds.

Data-Driven Forecast Enhancement

The SPoRT team focuses on improving weather forecasts using satellite data from NASA and NOAA. Its Sea Surface Temperature Composite product, shown here, is a blend of observations from multiple satellite sensors. SPoRT updates this high-resolution composite twice daily, providing global maps of sea surface temperatures, trends, and anomalies to decision-makers. Each update is promptly available to users, which include the National Weather Service, NOAA nowCOAST, and the NASA Disasters Mapping Portal.

In addition to unusually warm ocean waters, low vertical wind shear aided Milton’s intensification, said Patrick Duran, a hurricane expert with the SPoRT project. The storm is embedded in a low-shear environment, meaning there is little difference in the speed and direction of lower-level and upper-level winds. This allows a hurricane to build vertically.

Another contributing factor could have been Milton’s relatively small size. Smaller hurricanes are more prone to rapid increases or decreases in strength, Duran noted. “In this case, Milton’s small size likely facilitated its rapid intensification,” he said.

At 10:28 a.m. EDT October 7, the space station flew over Hurricane Milton and external cameras captured views of the category 5 storm, packing winds of 175 miles an hour, moving across the Gulf of Mexico toward the west coast of Florida. pic.twitter.com/MTtdUosiEc

— International Space Station (@Space_Station) October 7, 2024

Potential Impact and Preparations

On the morning of October 8, the hurricane had neared the northern coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, where destructive winds and storm surge were expected. That same morning, the National Hurricane Center reported that Milton underwent an eyewall replacement cycle, an internal storm process often associated with declining wind speeds but growth in the area of the wind field.

The storm is projected to turn northeast and accelerate toward Tampa Bay, Florida, on October 8 and 9, according to the National Hurricane Center. Forecasters warned of heavy rainfall in the state ahead of the storm’s arrival on land, as well as life-threatening wind and storm surge as it approaches and then crosses the Florida Peninsula. Most counties along the Gulf Coast, which include major population centers such as Tampa and Fort Myers, were under evacuation orders as of October 8.

As Milton completes its transit of the gulf, fluctuations in strength are likely as the storm structure changes, said the National Hurricane Center. Nonetheless, it will remain an extremely dangerous storm. “Even if the maximum wind speed decreases in the coming days, the storm will likely grow in size,” said Duran. “This could increase its impacts, especially by increasing storm surge along the coast.” The National Weather Service warns of storm surge accompanied by large waves for hundreds of miles along Florida’s gulf coast, with water levels reaching as much as 10–15 feet above the ground around Tampa Bay.

NASA’s Disasters Response Coordination System has been activated to support agencies responding to the storm, including the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Florida Geospatial Information Office. The team will be posting maps and data products on its open-access mapping portal as new information becomes available about flooding, power outages, precipitation totals, and other topics.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Wanmei Liang, using sea surface temperature data from NASA’s Short-term Prediction Research and Transition (SPoRT) center; VIIRS brightness temperature data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE, GIBS/Worldview, and the Joint Polar Satellite System (JPSS); and hurricane track data from NOAA’s National Hurricane Center.