Researchers at the University of Hawaiʻi have revealed that our galaxy, part of the Laniākea supercluster, might actually reside within a significantly larger cosmic structure, potentially centered around the massive Shapley concentration.

This discovery, emerging from the study of 56,000 galaxies, suggests that our cosmic neighborhood could be 10 times larger than previously estimated, challenging existing models of the universe’s structure.

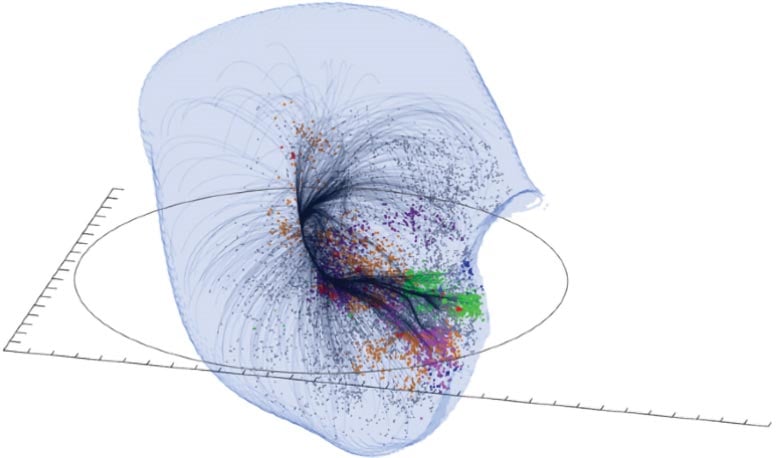

An international research team guided by astronomers at the University of Hawaiʻi Institute for Astronomy is challenging our understanding of the universe with groundbreaking findings that suggest our cosmic neighborhood may be far larger than previously thought. The Cosmicflows team has been studying the trajectories of 56,000 galaxies, revealing a potential shift in the scale of our galactic basin of attraction.

Expanding Galactic Understanding

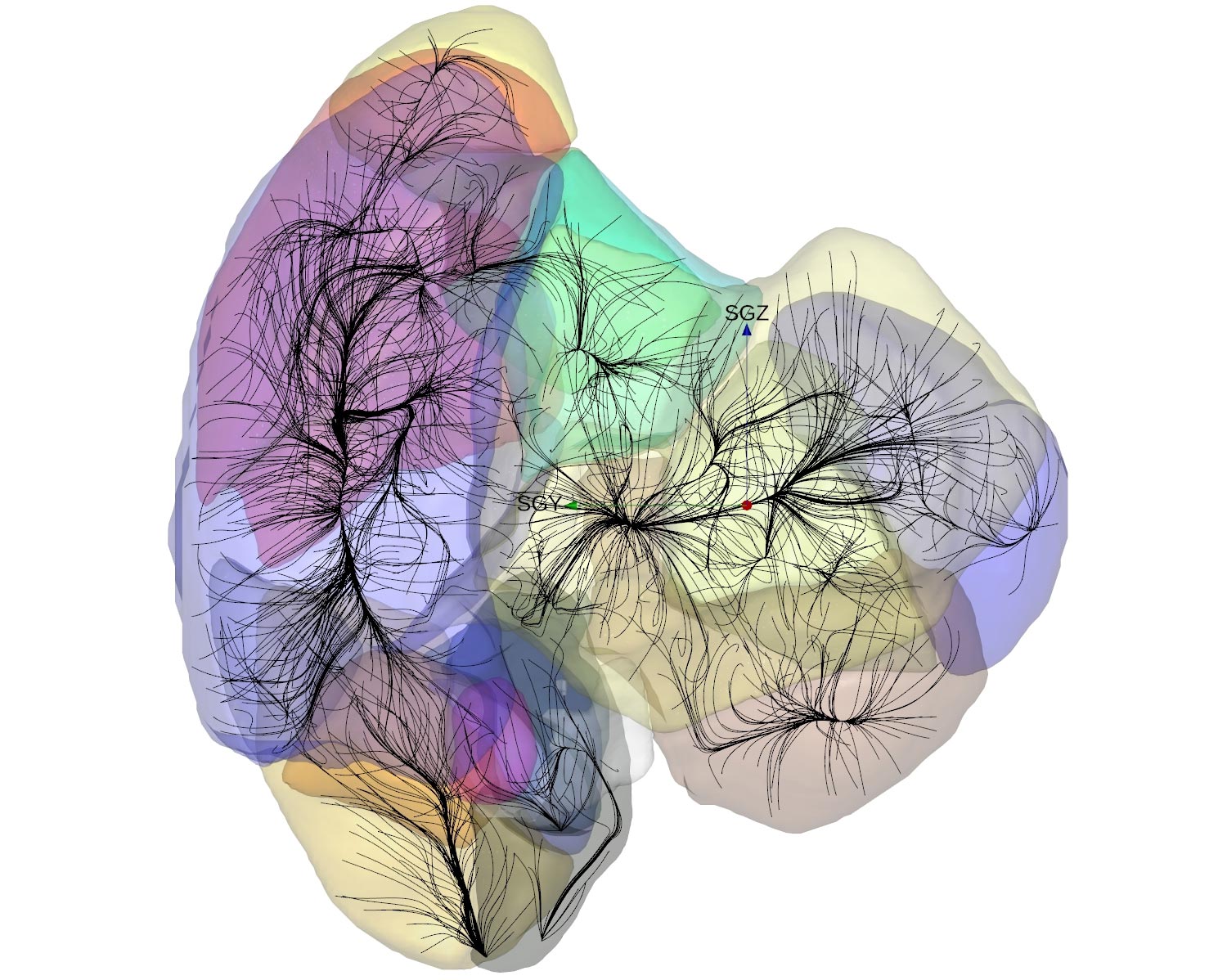

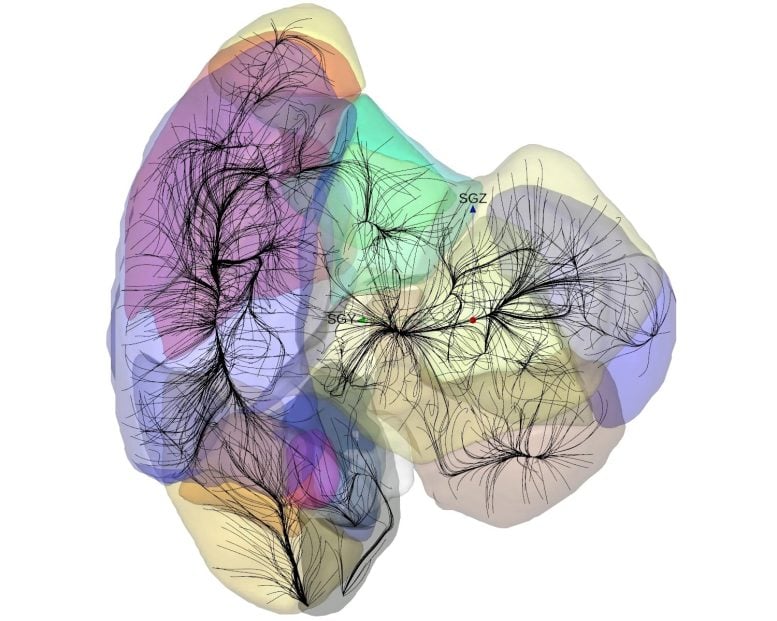

A decade ago, the team concluded that our galaxy, the Milky Way, resides within a massive basin of attraction called Laniākea, stretching 500 million light-years across. However, new data suggests that this understanding may only scratch the surface. There is now a 60% probability that we are part of an even grander structure, potentially 10 times larger in volume, centered on the Shapley concentration—a region packed with an immense amount of mass and gravitational pull. The findings were recently published in Nature Astronomy.

“Our universe is like a giant web, with galaxies lying along filaments and clustering at nodes where gravitational forces pull them together,” said UH Astronomer R. Brent Tully, one of the study’s lead researchers. “Just as water flows within watersheds, galaxies flow within cosmic basins of attraction. The discovery of these larger basins could fundamentally change our understanding of cosmic structure.”

The Enigma of Cosmic Scale

The universe’s origins date back 13 billion years when tiny differences in density began to shape the cosmos, growing under the influence of gravity into the vast structures we see today. But if our galaxy is part of a basin of attraction much larger than Laniākea, which means immense heaven in the Hawaiian language, it would suggest that the initial seeds of cosmic structure grew far beyond current models.

“This discovery presents a challenge: our cosmic surveys may not yet be large enough to map the full extent of these immense basins,” said UH astronomer and co-author Ehsan Kourkchi. “We are still gazing through giant eyes, but even these eyes may not be big enough to capture the full picture of our universe.”

Gravitational Forces

The researchers evaluate these large-scale structures by examining their impact on the motions of galaxies. A galaxy between two such structures will be caught in a gravitational tug-of-war in which the balance of the gravitational forces from the surrounding large-scale structures determines the galaxy’s motion. By mapping the velocities of galaxies throughout our local universe, the team is able to define the region of space where each supercluster dominates.

The researchers are set to continue their quest to map the largest structures of the cosmos, driven by the possibility that our place in the universe is part of a far more expansive and interconnected system than ever imagined.

For more on this discovery, see Astronomers Unveil Vast Gravitational Basins in the Local Universe.

Reference: “Identification of basins of attraction in the local Universe” by A. Valade, N. I. Libeskind, D. Pomarède, R. B. Tully, Y. Hoffman, S. Pfeifer and E. Kourkchi, 27 September 2024, Nature Astronomy.

DOI: 10.1038/s41550-024-02370-0

The international team is composed of UH astronomers Tully and Kourkchi, Aurelien Valade, Noam Libeskind and Simon Pfeifer (Leibniz Institut für Astrophysik Potsdam), Daniel Pomarede (University of Paris-Saclay) and Yehuda Hoffman (Hebrew University).