Comprehensive analysis of Moon maps has revealed multiple sources of water across various latitudes, indicating potential access points for future astronauts even near the equator.

Using data from the Moon Mineralogy Mapper, researchers have detailed the stability and distribution of water and hydroxyl on the Moon’s surface, uncovering geological activities that facilitate the appearance of these substances.

Lunar Water Distribution: Excavation and Sources

According to a new analysis of maps of the near and far sides of the Moon, there are multiple sources of water and hydroxyl in the sunlit rocks and soils, including water-rich rocks excavated by meteor impacts at all latitudes.

“Future astronauts may be able to find water even near the equator by exploiting these water-rich areas. Previously, it was thought that only the polar region, and in particular, the deeply shadowed craters at the poles were where water could be found in abundance,” said Roger Clark, Senior Scientist at the Planetary Science Institute and lead author of “The Global Distribution of Water and Hydroxyl on the Moon as Seen by the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3)” that appears in the Planetary Science Journal.

“Knowing where water is located not only helps to understand lunar geologic history, but also where astronauts may find water in the future.”

Mapping Techniques and Spectroscopy Insights

Clark and his research team, which includes PSI scientists Neil C. Pearson, Thomas B. McCord, Deborah L. Domingue, Amanda R. Hendrix and Georgiana Kramer, studied data from the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3) imaging spectrometer on the Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft, which orbited the Moon from 2008 to 2009, mapping water and hydroxyl on the near and far sides of the Moon in greater detail than ever before.

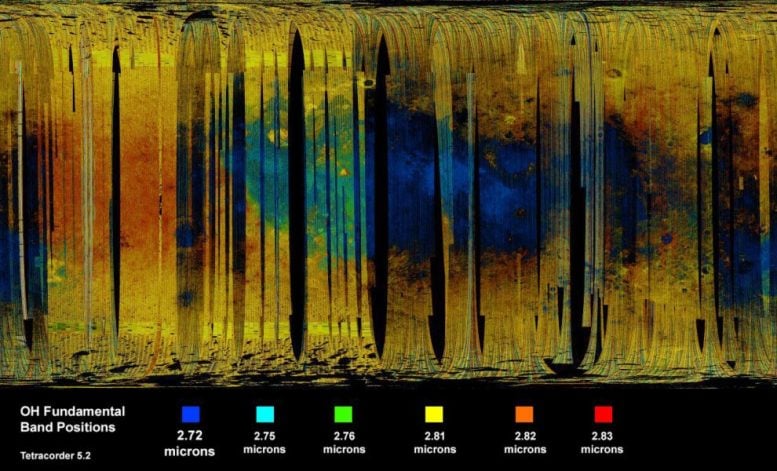

Locating water in the sunlit parts of the Moon uses infrared spectroscopy to search for the fingerprints of water and hydroxyl (a functional chemical group with one hydrogen and one oxygen atom) in the spectrum of reflected sunlight in the infrared. While a digital camera records three colors in the visible part of the spectrum, the M3 instrument recorded 85 colors from the visible spectrum and into the infrared.

Just like we see different colors from different materials, the infrared spectrometer can see many (infrared) colors to better determine the composition, including the water (H2O) and hydroxyl (OH). The water may be directly harvested by heating rocks and soils. Water might also be formed by chemical reactions liberating hydroxyl and combining four hydroxyls to create oxygen and water (4(OH) -> 2H2O + O2).

Lunar Surface Stability and Geological Impact

By studying the location and geologic context, Clark and his team were able to show that water in the lunar surface is metastable, meaning H2O is slowly destroyed over millions of years, but with hydroxyl, OH, remaining. A cratering event that exposes sub-surface water-rich rocks to the solar wind will degrade with time, destroying H2O and creating a diffuse aura of hydroxyl, OH, but the destruction is slow, taking thousands to millions of years.

Elsewhere on the lunar surface, there appears a patina of hydroxyl, probably created from solar wind protons impacting the lunar surface, destroying silicate minerals where the protons combine with oxygen in the silicates to create hydroxyl, in a process called space weathering.

“Putting all the evidence together, we see a lunar surface with complex geology with significant water in the sub-surface and a surface layer of hydroxyl. Both cratering and volcanic activity can bring water-rich materials to the surface, and both are observed in the lunar data,” Clark said.

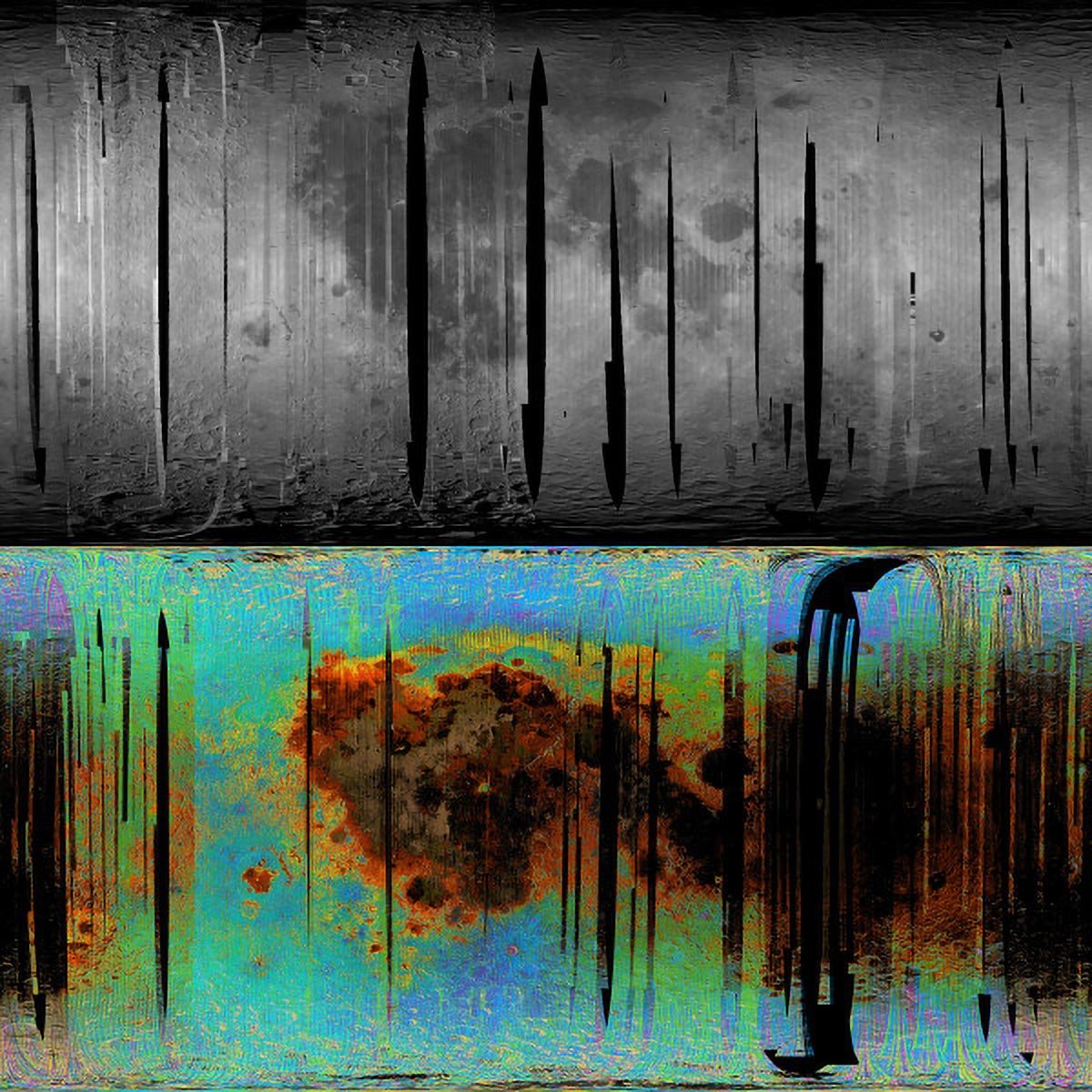

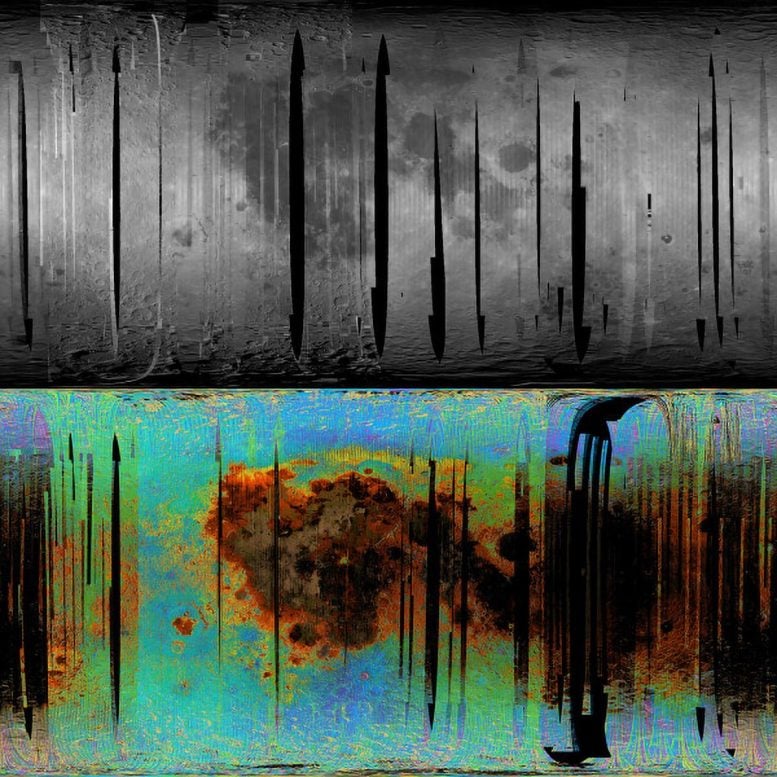

The Moon is made up of primarily two kinds of rocks: the dark mare which are basaltic (lava like that seen in Hawaii), and anorthosite rocks, which are lighter (the lunar highlands). The anorthosites contain a lot of water, the basalts very little. The two rock types also contain hydroxyl bonded to different minerals, shown in the figure below.

New Discoveries and The Behavior of Lunar Water

This study sheds new light on previously known mysteries. When the Sun is shining on the lunar surface at different times of day, the strength of water and hydroxyl absorptions change. That led to the calculation that a lot of water and hydroxyl had to be moving around the Moon on a daily cycle. However, this new study showed that very stable mineral absorptions of water and hydroxyl show the same daily effect, but on minerals, like pyroxene, a common igneous silicate mineral in the lunar soils, they do not evaporate at lunar temperatures.

The reason for this effect is instead due to a thin layer of enriched composition and/or soil particle size that is different from deeper into the soil. When the Sun is low in the lunar sky, light transmits through more of the top layer, strengthening the infrared absorptions, compared to when the Sun is high in the sky. There may still be water moving around, but to quantify how much, new studies will need to quantify the layering effects too. Lunar rover tracks are darker in images from the Apollo-era rovers, another indicator the surface layer is thin and different.

Related to the thin surface layer are the expressions of enigmatic features on the Moon called lunar swirls, diffuse patterns in visible light in several areas on the Moon. Magnetic fields are thought to play a role in swirl formation by diverting solar wind, which would also reduce hydroxyl production. A previous study led by PSI Senior Scientist Georgiana Kramer and co-authored by R. Clark showed lunar swirls are deficient in hydroxyl. The new study confirms that but also shows more complexity in that swirls are also low in water content but are sometimes higher in pyroxene content.

This new study with global hydroxyl maps also shows never-before-seen areas that are similar to known swirls, but have no diffuse patterns seen in visible light, and thus can only be seen in hydroxyl absorption. These new features may be old eroded swirls and include new types, including arcs and linear features. By mapping the Moon in new ways like this, the lunar surface is showing it is more complex than we imagined.

Reference: “The Global Distribution of Water and Hydroxyl on the Moon as Seen by the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3)” by Roger N. Clark, Neil C. Pearson, Thomas B. McCord, Deborah L. Domingue, Keith Eric Livo, Joseph W. Boardman, Daniel P. Moriarty, Amanda R. Hendrix, Georgiana Kramer and Maria E. Banks, 16 September 2024, The Planetary Science Journal.

DOI: 10.3847/PSJ/ad5837

Early work on data analysis for this study was funded by the Moon Mineralogy Mapper science team. Main funding for this study was supported by the NASA Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute 2016 (SSERVI16) Cooperative Agreement (80ARC017M0005) (TREX).