Research links the rapid extinction of dwarf megafauna on Cyprus to early human settlers, whose hunting practices decimated these species quickly after their arrival.

Researchers have solved a longstanding mystery about the extinction of dwarf hippos and elephants on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus.

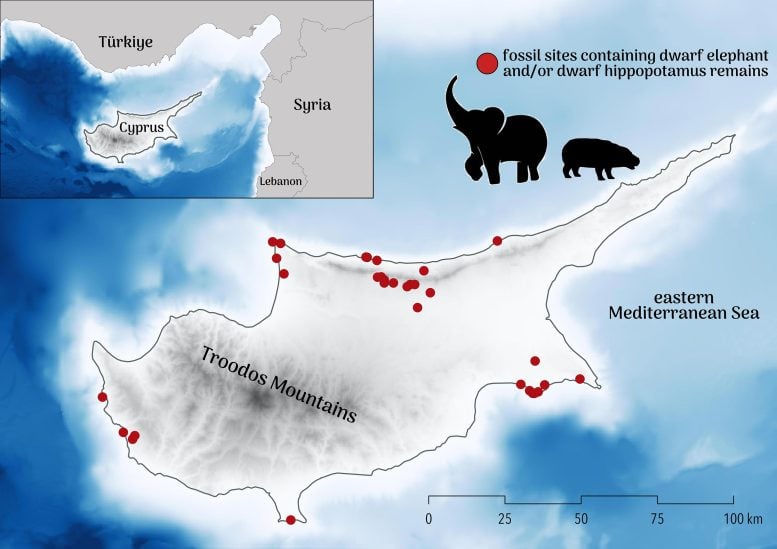

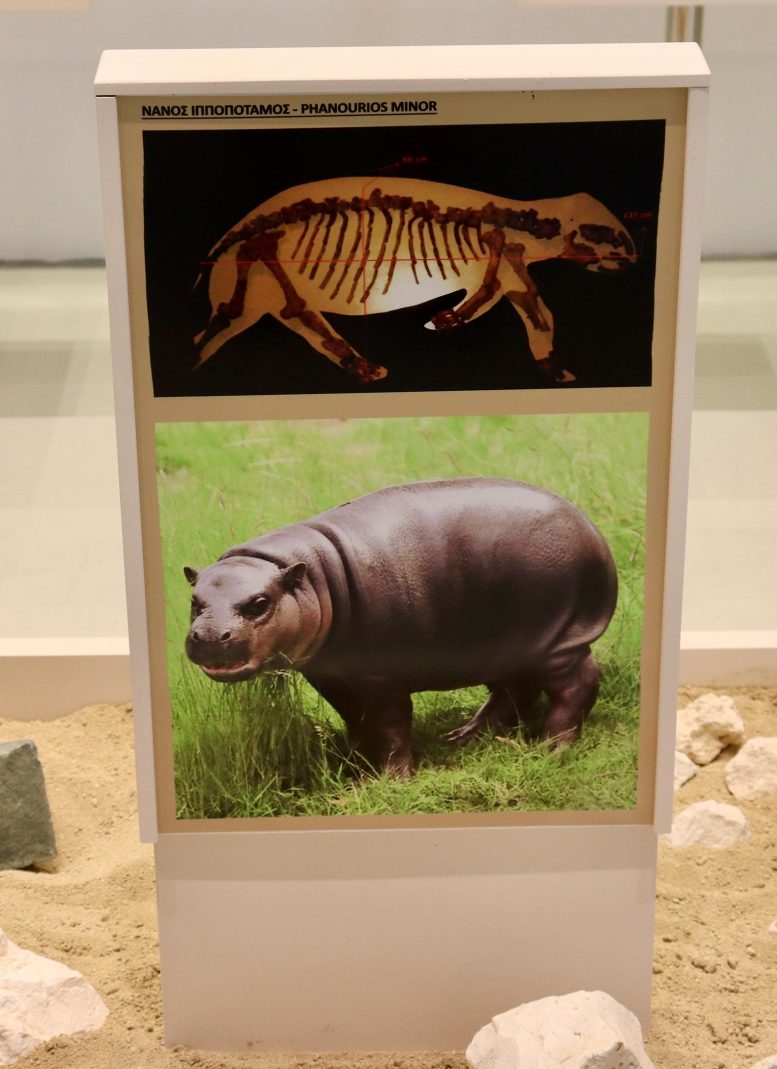

During the Late Pleistocene, Cyprus only had two species of megafauna present — the 500-kg dwarf elephant (Palaeoloxodon cypriotes) and the 130-kg dwarf hippo (Phanourios minor). However, both species disappeared shortly after the arrival of Paleolithic humans around 14,000 years ago.

Human Impact on Dwarf Species Extinction

New research indicates that paleolithic hunter-gatherers on Cyprus could have first driven dwarf hippos, and then dwarf elephants to extinction in less than 1000 years.

These findings refute previous arguments that suggested the introduction of a small human population on the island could not have caused these extinctions so quickly.

Advanced Modeling Reveals Extinction Dynamics

In the study, recently published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, the researchers built mathematical models combining data from various disciplines, including paleontology and archaeology, to show that paleolithic hunter-gatherers in Cyprus are most likely the main cause of the extinction of these species due to their hunting practices.

The researchers used data-driven approaches to reveal the impact of rapid human settlement on driving the extinction of species soon after their arrival.

Using detailed reconstructions of human energy demand, diet composition, prey selection, and hunting efficiency, the model demonstrates that 3,000–7,000 hunter-gatherers predicted to have occurred on the island were likely responsible for driving both dwarf species to extinction.

Concluding Insights on Human-Caused Extinctions

“Our results therefore provide strong evidence that palaeolithic peoples in Cyprus were at least partially responsible for megafauna extinctions during the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene. The main determinant of extinction risk for both species was the proportion of edible meat they provided to the first people on the island,” says lead author Professor Corey Bradshaw of Flinders University.

“Our research lays the foundation for an improved understanding on the impact small human populations can have in terms of disrupting native ecosystems and causing major extinctions even during a period of low technological capacity.”

Predictions in the model matched the chronological sequence of megafauna extinctions in palaeontological records.

Co-author Dr. Theodora Moutsiou says: “Cyprus is the perfect location to test our models because the island offers an ideal set of conditions to examine whether the arrival of populations of humans ultimately led to the extinction of its megafauna species. This is because Cyprus is an insular environment and can provide a window back in time through our data.”

Previous findings by Professor Bradshaw and collaborators have shown that large groups of hundreds to thousands of people could have arrived on Cyprus in two to three main migration events in less than 1000 years.

Reference: “Small populations of Palaeolithic humans in Cyprus hunted endemic megafauna to extinction” by Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Frédérik Saltré, Stefani A. Crabtree, Christian Reepmeyer and Theodora Moutsiou, 1 September 2024, Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2024.0967

This research was funded by the European Regional Development Fund and the Republic of Cyprus through the Research and Innovation Foundation for project MIGRATE.

The project Modelling Demography and Adaptation in the Initial Peopling of the Eastern Mediterranean Islandscape (MIGRATE, EXCELLENCE/0421/0050) is hosted at the Archaeological Research Unit, University of Cyprus and coordinated by Dr. Theodora Moutsiou.