Researchers have determined that reducing plastic littering by 32% by the year 2035 is necessary to prevent further water pollution.

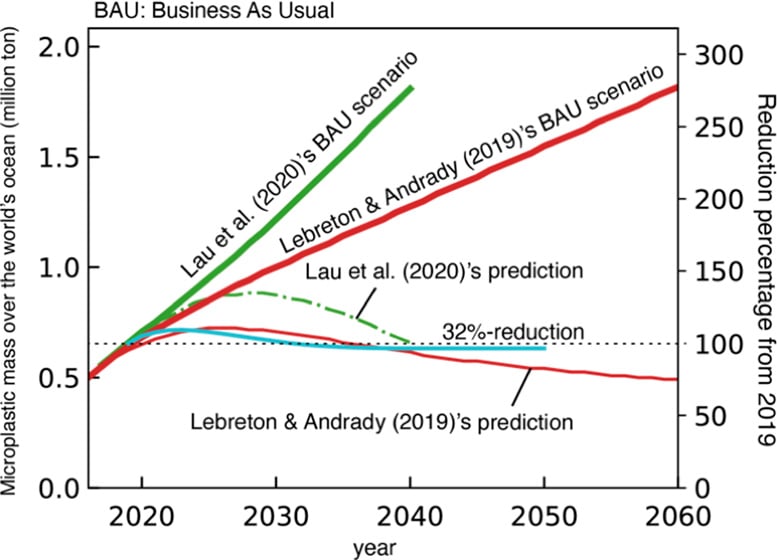

A report published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin by researchers from Kyushu University has, for the first time, established a clear numerical target for addressing global marine plastic pollution. Through their mapping of plastic waste movement and its impacts on the oceans, the team determined that a minimum 32% reduction in plastic littering is required by 2035 to avert further harm to marine environments.

Marine plastic pollution has been a growing issue for the world, and unless considerable interventions are placed the situation will only get worse. For several years, Professor Atsuhiko Isobe from Kyushu University’s Research Institute for Applied Mechanics has been working to monitor and track plastic pollution in the ocean. In 2022, his research team reported that an estimated 25.3 million metric tons of plastic waste has entered our oceans, and nearly two-thirds of that cannot be monitored.

Tracking Plastic Waste with Advanced Models

“My research focuses on tracking where plastic waste goes after being released into water sources such as rivers and oceans. We use computer models to track how plastics move and break down over time,” explains Chisa Higuchi, first author of the study and Post‐doctoral Fellow in Isobe’s lab.

Plastic waste persists for a long time; however, larger plastics gradually break down into smaller plastic particles. While larger plastics can be removed more easily, when they become smaller than 5 mm in size they are categorized into microplastics, making them more difficult to collect, and fish are more likely to consume them. So, even if littering stopped today, the amount of microplastics would continue to increase.

At the 2019 G20 Osaka Summit, representatives introduced the Osaka Blue Ocean Vision, with the aim to stop the increase in marine plastic pollution by 2050. This initiative seeks to improve waste management strategies around the world through international collaboration.

Higuchi explains, “We wanted to figure out what would be the ideal scenario for the Osaka Blue Ocean Vision to succeed. So, we utilized computational modeling along with fieldwork studies to understand where and how plastics flow into the oceans.”

Plastic Breakdown and Emission Routes

Researchers studied how long it takes for different types of plastics to break down into smaller particles. Additionally, they collected data from plastic emission routes from rivers and other resources leading to the ocean.

“What we came up with are something akin to weather forecast maps, but instead of showing when and where it will rain, these maps show different scenarios on when and where plastics will end up,” explains Higuchi.

According to their trajectory, reducing plastic waste entering oceans by 32%, equivalent to 8.1 million tons, by 2035 would eventually result in more than 50% less plastic in the oceans by 2050. The effect is even more pronounced in heavily polluted areas like the Yellow and East China Seas. Here, plastic waste could be reduced by up to 63% under the team’s scenarios.

“Not only does this give the Osaka Blue Ocean Vision concrete targets, but it also gives governments and businesses metric goals,” says Higuchi. “Naturally, we need to go beyond cleaning existing pollution; we must cut new plastic waste entering our oceans and rivers.”

“This target is attainable if we use strategies like improving waste management, promoting reusable alternatives to single-use plastics, and enhancing public awareness,” concludes Isobe. “Many people can be pessimistic when hearing about the ongoing plastic waste problem in our lives. But I remain optimistic that we can find our way out of this predicament.”

Reference: “Reduction scenarios of plastic waste emission guided by the probability distribution model to avoid additional ocean plastic pollution by 2050s” by Chisa Higuchi and Atsuhiko Isobe, 8 August 2024, Marine Pollution Bulletin.

DOI: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.116791

The study was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development, the Japan Science and Technology Agency, and the Japan International Cooperation Agency.