Over the past century, the number of working women in Western countries has steadily increased. However, numerous studies show that it is still primarily women who have to manage the balancing act between parenthood and working life. Compared to fathers and childless women, mothers often have a less straightforward career path and face greater hurdles to career advancement.

Little research has been done on what happens to women’s employment trajectories from midlife when childrearing efforts are likely lessened. In a recent study published in the European Journal of Population, Angelo Lorenti of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR) with Jessica Nisén (University of Turku), Letizia Mencarini (Bocconi University), and Mikko Myrskylä (MPIDR) compared how the working lives of mothers, fathers and childless individuals evolve after midlife (from the age of 40).

The researchers looked at three countries: Italy, Finland and the United States. “All three countries have very different conditions for parents. While there is no parental leave or maternity leave in the US, parents in Finland receive full state support, including parental leave and job security. In between is Italy, where family replaces state support. But there is no job security,” says Lorenti.

The study looked at the life stage between the ages of 40 and 74 by gender, number of children and education. It looked at how many years were spent in employment, joblessness and retirement. Data from the Italian Survey on Household, Income and Wealth (SHIW), Finnish register data and the US Panel Study on Income Dynamics (PSID) were used.

Mothers in some cases work up to almost 11 years less than fathers

The results of the analysis paint a very diverse picture for all three countries. “In Finland, as expected, we found very small differences between mothers and fathers. We can see that both men and women work for pay longer than childless individuals. In fact, we were able to read from the data that childless people in Finland have a shorter working life because they often have a lower socio-economic status,” the researcher explains.

In Italy, the picture is quite different. “The more children a woman has, the shorter her working life. The opposite is true for men. But childless women in Italy are probably making a conscious choice. They don’t have children in order to have a career,” says Lorenti. The researchers note, however, that the differences between mothers and fathers in Italy diminish as the level of education increases.

The results from the United States fall between Italy and Finland. “Here, we observed differences in working life between men and women only when there were two or more children, and education only partially interact with gender and number of children; that mothers’ disadvantage is evident only among low educated with two children and more,” says Lorenti.

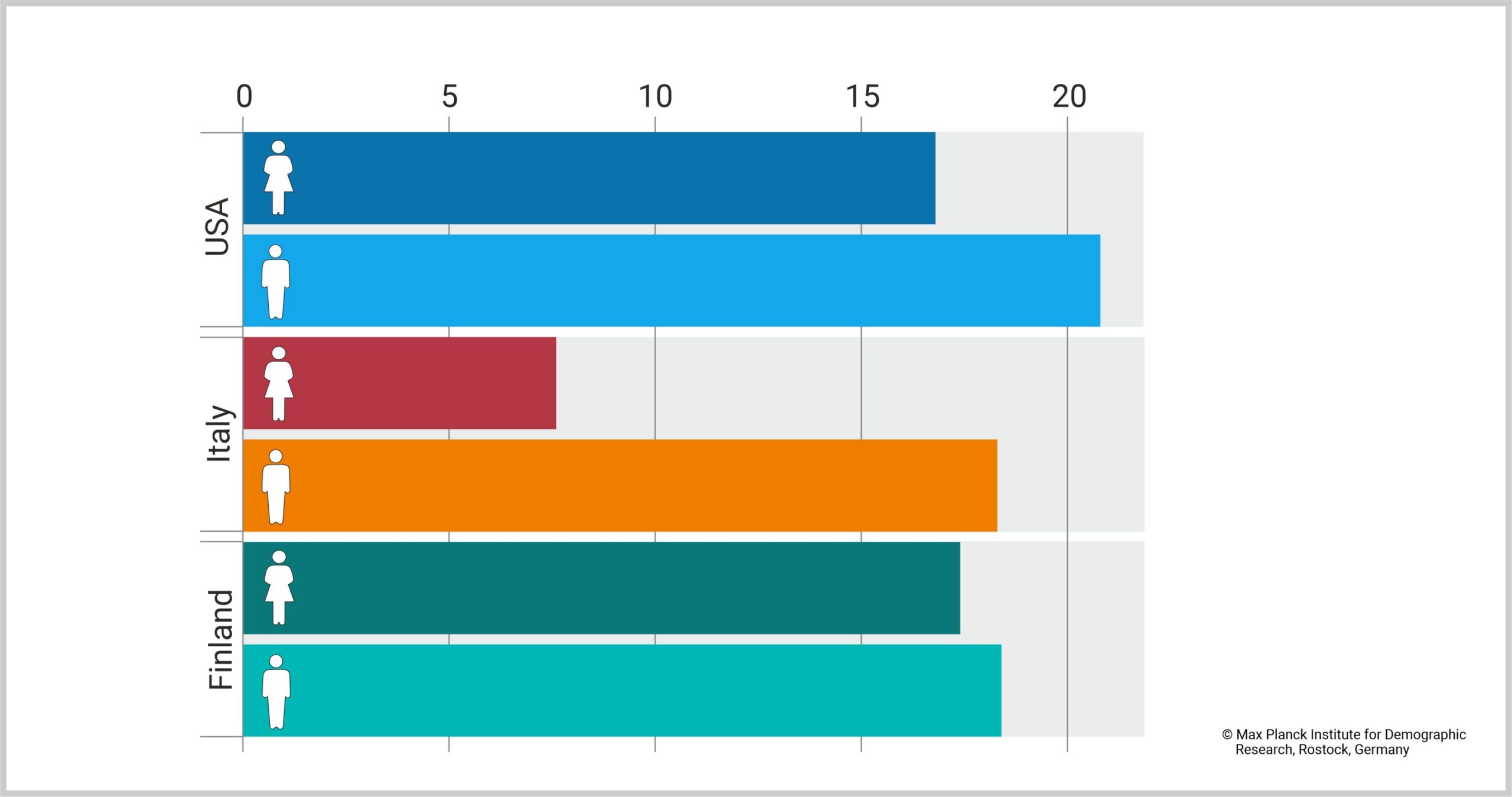

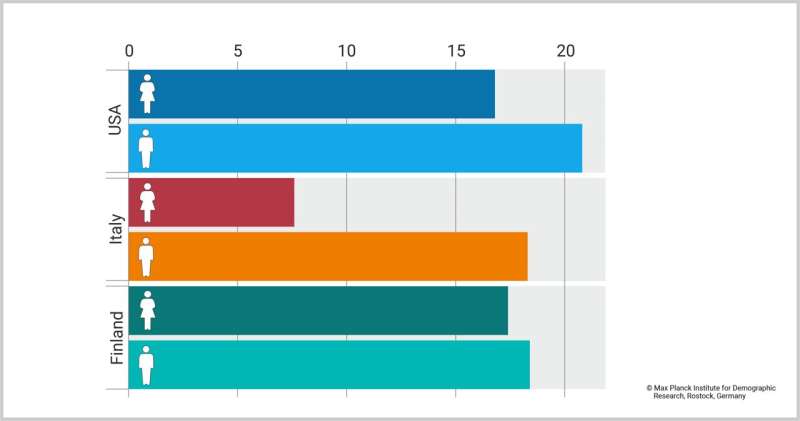

The cross-country comparison is illustrated by the example of individuals with three children. While in Finland the gender difference is one year, i.e. at the age of 40 mothers still work for pay for about 17.4 years and fathers for 18.4 years, the difference in the U.S. is greater.

Here the gender difference is about 4 years (mothers 16.8 years and fathers 20.8 years). In Italy, the very traditional role model is evident, as mothers aged 40 and over only work for pay for 7.6 years, while fathers in these families still work for 18.3 years. This is a difference of about 11 years.

Everyone benefits from better support for mothers

On paper, the difference from midlife in the working lives of mothers and fathers may not seem that large overall, but the disadvantage mothers suffer is substantial.

“We only looked at the period after having children. This means that the time lost due to previous childbirths and childcare has to be added. In Italy, for example, mothers have a much shorter working life, and this obviously has an impact on pensions and care in old age. Mothers are at a huge disadvantage here,” says Lorenti.

Investing in women also pays off in terms of stabilizing pension systems. “In countries like Italy and the US, it can pay to support women at the population level to extend their working lives—and not necessarily only at the end of their working lives. That makes a big difference ensuring better retirement security for mothers,” says Lorenti.

More information:

Angelo Lorenti et al, Gendered Parenthood-Employment Gaps from Midlife: A Demographic Perspective Across Three Different Welfare Systems, European Journal of Population (2024). DOI: 10.1007/s10680-024-09699-2

Provided by

Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research

Citation:

Mind the gap: Italian moms with 3+ kids work far fewer years than dads, while Finland shows equality (2024, June 5)

retrieved 5 June 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-06-mind-gap-italian-moms-kids.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.