A computational model of the more than 26 million atoms in a DNA-packed viral capsid expands our understanding of virus structure and DNA dynamics, insights that could provide new research avenues and drug targets, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign researchers report in the journal Nature.

“To fight a virus, we want to know everything there is to know about it. We know what’s inside in terms of components, but we don’t know how they’re arranged,” said study leader Aleksei Aksimentiev, an Illinois professor of physics. “Knowledge of the internal structures gives us more targets for drugs, which tend to focus on receptors on the surface or replication proteins.”

Viruses keep their genetic material—either DNA or RNA—packaged in a hollow particle called a capsid. While the structures of many hollow capsids have been described, the structure of a full capsid and the genetic material inside it has remained elusive.

For this first look at a complete packaged viral genome, the researchers focused on HK97, a virus that infects bacteria. It has been well-studied experimentally, so the Illinois group would be able to compare its simulations to what has been found previously, said Aksimentiev, who also is affiliated with the Beckman Institute of Advanced Science and Technology at Illinois.

“We know from experiments that the capsid has a portal, and there is a motor protein there that pushes the DNA in. We also know the structure of the capsid from experiments. We know the genetic sequence, but what was not known was the structure of the packaged genetic material inside.”

Figuring out the structural dynamics of genome packaging has challenged researchers for several reasons. It cannot yet be seen experimentally, so simulation on a supercomputer is required. However, a simulation can either show great detail for a very short time or less detail for a longer time.

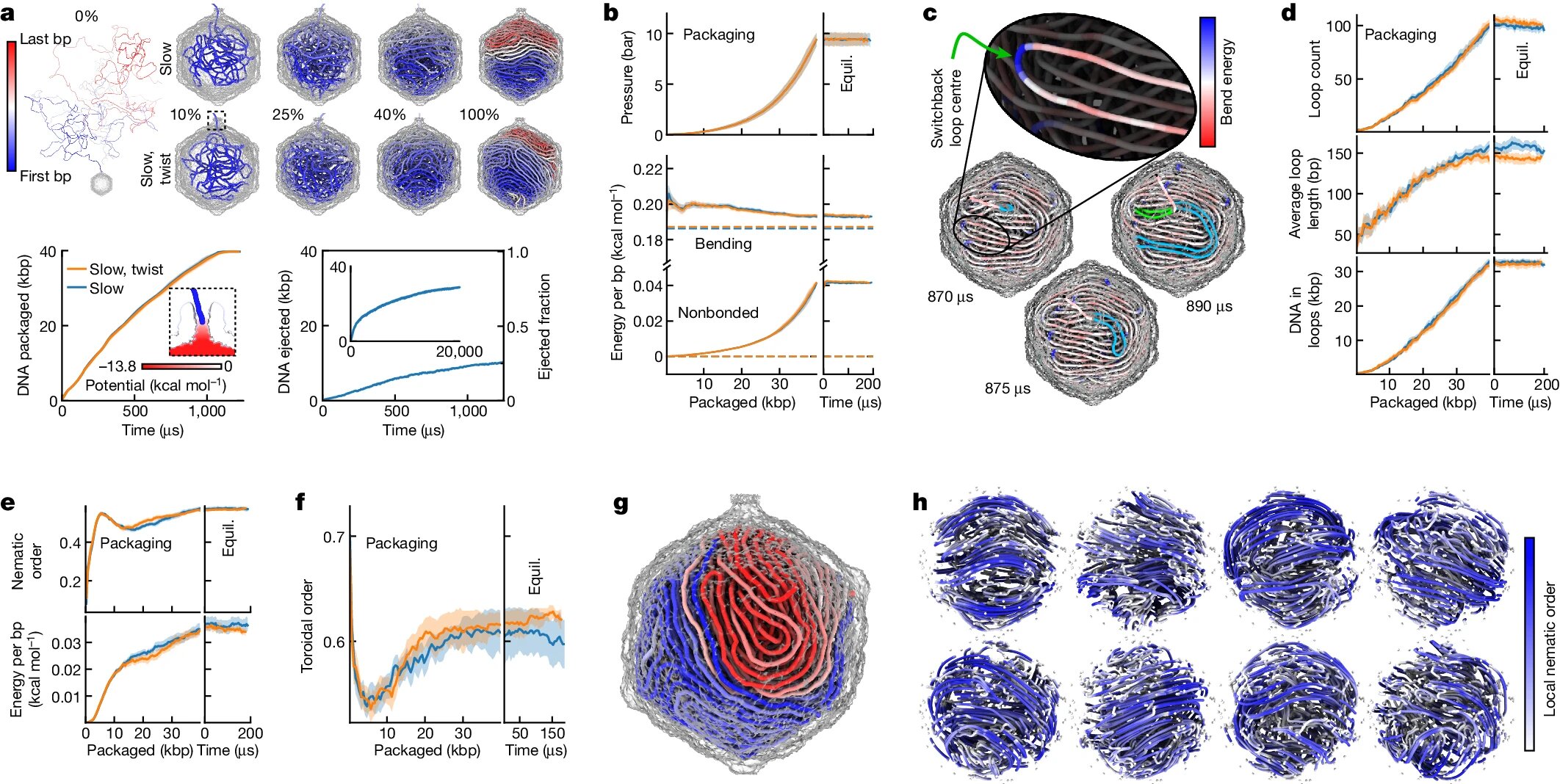

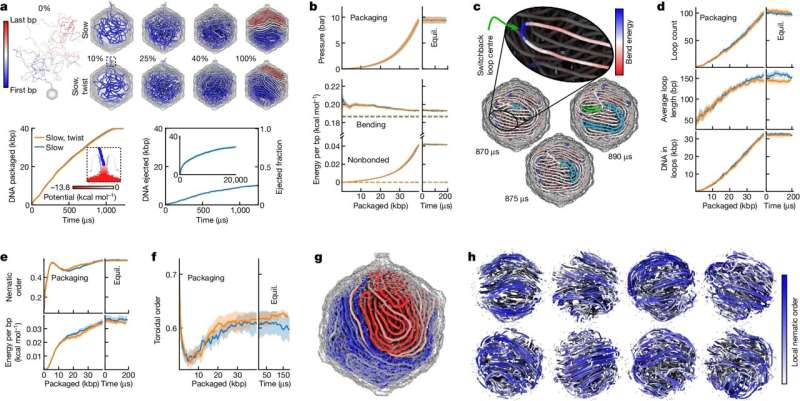

The Illinois group developed a multiresolution approach to DNA simulation, looking at the problem at multiple levels of resolution and time length and putting all the information together to get a complete picture of the process. Having previously used and validated it in experiments involving DNA origami, they now applied the multiresolution approach to HK97.

The result was the first atom-level look at the viral DNA packaging process and the structural properties and fluctuations when the DNA is fully contained in the capsid.

They found that the DNA formed switchback loops as it was pushed into the capsid, an important finding as it is similar to how DNA is organized in eukaryotic cells. They also found that the DNA organized itself into domains conforming to the topology of the capsid. The process resulted in slightly different configurations of loops and topologies of DNA in each particle simulated.

“These differences show that the concept of individuality is not exclusive to animals and plants but extends down to viruses, the most primitive form of gene-replicating structures,” Aksimentiev said. “This opens another dimension to looking at infectivity and whether these differences among viruses account for variability in their ability to infect.”

The simulations did reveal common structural features and defects, particularly at the edges and corners of the capsid, where its shape has the greatest influence on the DNA inside. These features could be potential targets for drug development, Aksimentiev said.

“We believe this is just the beginning for our methodology, the first study to look at the structure of a viral genome,” Aksimentiev said. “With bigger, faster computers and more knowledge from experiments, we will eventually be able to computationally resolve the structures of genomes from other viral species, including RNA viruses, which are more complicated as they self-assemble.”

“The more we know about these viruses, the more we can combat them or harness them for applications such as combating bacteria that have grown resistant to antibiotic use,” Aksimentiev said.

More information:

Aleksei Aksimentiev, The structure and physical properties of a packaged bacteriophage particle, Nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07150-4. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-07150-4

Provided by

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Citation:

First atom-level structure of packaged viral genome reveals new properties and dynamics (2024, March 6)

retrieved 6 March 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-03-atom-packaged-viral-genome-reveals.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.