A dead zone in the ocean is as bad as it sounds, and having no information about dead zones’ scope and path is worse. However, scientists at Michigan State University (MSU) have discovered a birds-eye method to predict where, when, and how long dead zones could persist across large coastal regions.

“Understanding where these dead zones are and how they may change over time is the first crucial step to mitigating these critical problems. But it is not easy by using traditional methods, especially for large-scale monitoring efforts,” said Yingjie Li, who did the work as a Ph.D. student at MSU’s Center for System Integration and Sustainability (CSIS). He is currently a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University.

Dead zones—technically known as hypoxic—are water bodies degraded to the point where aquatic life cannot survive because of low oxygen levels. They’re a problem mainly in coastal areas where fertilizer runoff feeds algae blooms, which then die, sink to the water’s bottom and decay. That decay eats up oxygen dissolved in the water, suffocating living life such as fish and other organisms that make up vibrant living waters.

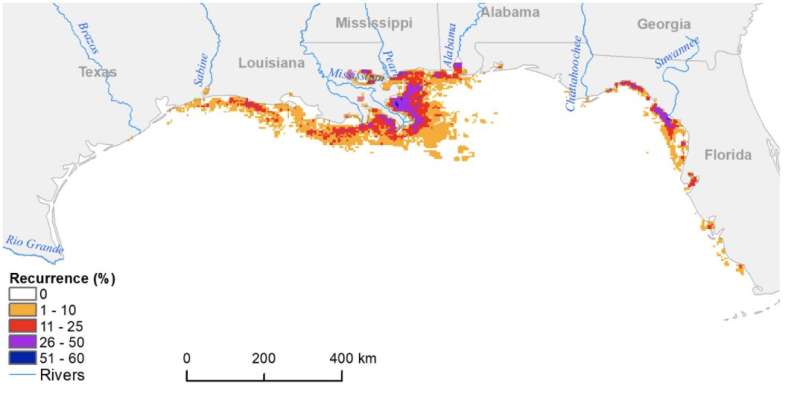

Dead zones can be hard to identify and track, and usually have been observed by water samples. But as reported in Remote Sensing of the Environment, scientists have figured out a novel way to use satellite views to understand what’s happening deep below the ocean’s surface. They used the Gulf of Mexico at the mouth of the Mississippi River as a demonstration site.

The group supplemented data from water sampling with different ways to use satellite views over time. In addition to predicting the size of hypoxic zones, the study provides additional information on where, when, and how long hypoxic zones persist with greater detail, and enables modeling hypoxic zones at near-real-time.

Since 1995, at least 500 coastal dead zones have been reported near coasts covering a combined area larger than the United Kingdom, endangering fisheries, recreation and the overall health of the seas. Climate change is likely to exacerbate hypoxia.

The research group notes the need to initiate a global coast observatory network to synthesize and share data for better understanding, predicting and communicating the changing coasts. Currently, such data is difficulty to come by. And the stakes are higher, as fertilizer applied in a field can become runoff in one part of a body of water miles away. The group points out that the telecoupling framework, which enables understanding of human and natural interactions near and far, would be useful to see the big picture of a problem.

“Damages to our coastal waters are a telecoupling problem that spans far beyond the dead zones—distant places that apply excessive fertilizers for food production and even more distant places that demand food. Thus, it’s critical we take a holistic view while employing new methods to gain a true understanding,” said Jianguo “Jack” Liu, MSU Rachel Carson Chair in Sustainability and CSIS director.

Besides, Li and Liu, “Satellite prediction of coastal hypoxia in the northern Gulf of Mexico” was written by Drs. Samuel Robinson and Lan Nguyen from the University of Calgary.

More information:

Yingjie Li et al, Satellite prediction of coastal hypoxia in the northern Gulf of Mexico, Remote Sensing of Environment (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.rse.2022.113346

Provided by

Michigan State University

Citation:

Satellites cast critical eye on coastal dead zones (2022, November 21)

retrieved 21 November 2022

from https://phys.org/news/2022-11-satellites-critical-eye-coastal-dead.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.