As the calendar flips to July, a long-awaited federal policy will kick in aimed at cutting the amount of pollution from cars and trucks, while trying to keep prices at the pump affordable.

The clean fuel regulations were first proposed in 2016, but they’ve faced delays and revisions along the way.

Although the new policy faces political opposition, it has received support from several environmental groups. Industry likes it, too.

“I want to reassure Canadians that it is a good policy, it is a good regulation, it will deliver significant [emission] reductions,” said Bob Larocque, president and CEO of the Canadian Fuels Association, which represents companies that process crude oil and bring products to the market.

There won’t be much of a change to pump prices across the country on July 1, experts say, although there will be a noticeable increase several years down the road.

That’s in addition to existing provincial and federal taxes on fuel, which are likely to entice more drivers to make the switch to electric vehicles.

The price impacts of the regulations will largely be based on how refineries and the fuel industry decide to comply, which experts say remains a big unknown.

Industry on board

The clean fuel standard kicks in on Canada Day, but the requirements to comply are relatively easy for refiners and fuel importers.

Add in the fact that many provinces already have clean fuel or fuel-blending regulations in place, and experts aren’t predicting an immediate change to pump prices.

“The policy has a pretty soft start because what it’s requiring is to some extent even less than what is actually being required of other pre-existing policies,” said Michael Wolinetz, a partner at Vancouver-based Navius Research, which provides consulting services on energy and the environment.

“We’re not expecting the policy to have any real bite until around 2025.”

One of the reasons industry likes the policy is because the federal government isn’t mandating a specific method to reduce pollution from the transportation sector, but instead leaves it largely up to individual companies to choose how they want to comply.

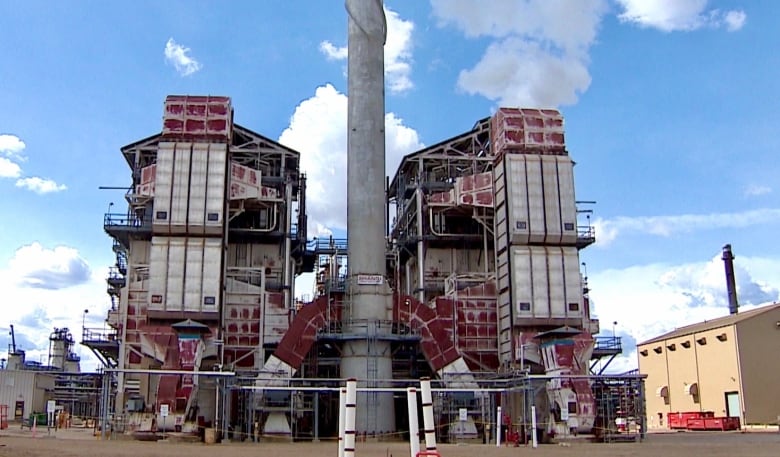

Companies have to achieve carbon emission reduction targets each year by earning credits through improvements to production facilities (such as building a carbon capture and storage facility at a refinery), lowering the carbon intensity of the actual fuel (by adding more ethanol, for instance) and by offering electric vehicle charging and hydrogen vehicle fuelling.

There’s also a credit trading system that allows companies to spend money to comply.

Adding more ethanol to gasoline and diesel is likely the most common way that industry will comply, say experts, because it’s already being done, just in smaller quantities.

Pain at the pumps

As the clean fuel requirements ramp up, so will prices at the pump as fuel companies face higher expenses, such as the purchase of more biofuels.

By 2030, the Parliamentary Budget Office predicts a price increase of 17 cents per litre — although it warns this is considered an upper limit. Experts agree, saying that estimate is likely the maximum price impact.

“There’s a zero per cent chance it would be worse than what the Parliamentary Budget Office is saying,” said Wolinetz, who predicts a cost impact of under 10 cents a litre by 2030.

Environment and Climate Change Canada estimates a price increase at the pumps by 2030 of anywhere between six and 13 cents per litre for gasoline. That’s on top of the 37 cents the carbon tax could add to a litre of gasoline by 2030, as well as all of the other federal and provincial (and some municipal) taxes charged on the purchase of gasoline and diesel.

There’s also the volatility of oil prices to consider and the cost of producing and transporting fuel. Add it all up and experts say the pain at the pumps could drive a large rise in electric vehicle sales over the next decade.

“[On] July 1, people aren’t really going to notice anything. But every year, as that target begins to bind more and more, then the cost curve starts to get pretty steep,” said Ross McKitrick, an economics professor at the University of Guelph in Ontario, who has co-authored a study modelling the economic effects of the clean fuel regulations.

Ottawa is OK with high pump prices down the road, he said, because “they just want to try to get people to switch over to EVs.”

Tailpipe emissions on the rise

The federal government’s focus on reducing the carbon intensity of fuels is understandable, considering how emissions from the transportation sector have increased by 16 per cent since 2005.

Overall, tailpipe emissions from all of the cars, trucks, SUVs and freight vehicles are a major obstacle toward Canada reaching its climate targets.

The transportation sector is the second-largest source of emissions in the country — behind the oil and gas sector — accounting for about 25 per cent of total emissions.

“If we actually want to reach our emissions reductions targets, this is the kind of policy that we need to be implementing,” said Michelle Coates Mather, executive director of the Canadian Transportation Alliance, a not-for-profit think-tank that researches the future of road transportation.

Canada ranks far below the global median for biofuel usage, according to a study released by the organization in February.

Increased demand for biofuels

Producing more ethanol in Canada seems like a natural fit, considering the amount of canola and soy that are grown. However, the country is already having to rely on imports to meet existing federal and provincial requirements.

“We will be importing. We have long imported ethanol from America, so that’s not a change,” said Ian Thomson, president of Advanced Biofuels Canada, an industry association.

Still, Thomson said, the clean fuel regulations could substantially change the country’s biofuel sector because of the increased demand in the years to come.

“It is changing the face of the industry,” he said.

Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault says the federal government will help Atlantic Canadians ‘get off home heating oil.’

Canadian companies have largely relied on importing U.S. ethanol produced from corn. In the past, imports have come from as far away as Brazil, where ethanol is produced using sugar cane.

As the clean fuel regulation requirements increase each year, the amount of ethanol, biodiesel and renewable diesel will rise.

Canada needs to increase the amount of biofuel production or else “we could be reliant on the United States by 2030 for up to 15 per cent of our fuel, which today we are not,” said Larocque, with the Canadian Fuels Association.

The demand for ethanol could soar, especially as more U.S. states adopt their own clean fuel policies.

“You do face the difficulty that all of a sudden, everyone is looking for the [same] product at once,” said the University of Guelph’s McKitrick.

“Most of the risk here is in the direction of cost surprises to the upside, rather than the downside.”