As Nova Scotians grapple with the growing effects of climate change, new research is attempting to help clarify how those changes are affecting their lungs.

Climate change can have a range of effects on lung health: wildfires fill the air with harmful particles; hot and humid conditions trap pollution close to the ground; longer growing seasons produce more pollen.

In recent years, these effects have started to manifest in Nova Scotia.

Tracy Cushing has been a registered respiratory therapist for nearly 30 years — but last year was the first time she can remember seeing so many patients affected by wildfire smoke; Cushing says hot and humid summer conditions are taking more of a toll on patients as well.

“Summers have been particularly difficult for many people with COPD over the last few years, as everything is getting hotter.”

Now a Dalhousie University researcher is aiming to provide a better understanding of exactly how those changes are affecting lung health, with the goal of providing health officials and the public the tools they need to respond.

“Even without the wildfires, there are climate-related changes to our air quality that are impacting people’s lung health,” says Dalhousie respiratory epidemiologist Sanja Stanojevic.

“It’s all about having the information so that people are aware … and I think that as people become more aware, it’s going to be more important for scientists and in the community to ensure that people have access to timely and accurate information about what they can do to mitigate any of those changes.”

Low-cost monitors provide localized data

Atlantic Canada is fortunate to have good air quality relative to the rest of Canada, says Stanojevic (though she notes the region has higher rates of smoking and non-smoking related lung health issues).

But as a consequence, little research has been done on the connection between lung health and climate change in some parts of the region.

Nonetheless, Stanojevic says the research from other areas shows the consequences can be severe: exposure to PM2.5 (the small particulate matter that’s the main component of wildfire smoke), for instance, affects lung development and increases rates of lung disease; poor air quality and high temperatures can exacerbate symptoms such as coughing or difficulty breathing in people with COPD and asthma.

A recent national study showed even relatively low levels of air pollution can negatively affect lung function.

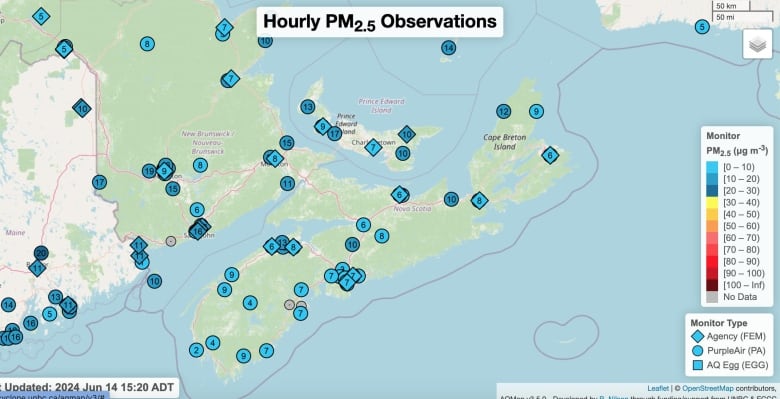

But much of the research to date has been based on government monitors, which are strategically placed around the country but only cover a small geographic area. “Generally, these monitors aren’t in the areas that need them most.”

To fill in this picture in Nova Scotia, Stanojevic is leading a project to install a network of low-cost monitors around the province to help provide localized information about air quality, and to find a way to translate that to information the public can use.

Changes at local level can make a difference

Robert MacDonald, CEO of LungNSPEI, which is supporting the project by helping distribute the monitors, says the organization has traditionally focused on environmental threats such as radon, the second-leading cause of lung cancer.

But as other environmental threats such as wildfires have emerged, the organization has recognized the supporting research examining the effects of a changing climate.

“With climate change, we know it’s a global thing, but it’s the little things that we can do when it comes to policies and procedures at the local level that can help make a difference.”

In New Brunswick, NB Lung has already explored a similar approach, participating in a pilot project with Environment and Climate Change Canada to use citizen scientists to place low-cost sensors across the province.

“We wanted to have more dense data so that we could see in times of heightened wildfire smoke, but also residential burning in the winter … what was going on in these communities,” says NB Lung CEO Melanie Langille.

Already, Langille says that the network has helped trace impacts from wildfires in other places (data is available on a near real-time map, where people can look at the information from each sensor).

“We were able to literally see the smoke come into our province as our [sensors] were lighting up on the map.”

Langille says the organization is working to also set up monitors in provincial parks, with the goal of having 50 sensors across the province.

‘Kind of this perfect storm’

In Nova Scotia, Stanojevic says the data from the sensors being set up in this province — which will also involve working with citizen scientists and marginalized communities — will also eventually be available to the public, with a website where people can see the data from their local air monitors.

Researchers will also be analyzing what changes in local air quality mean for hospitalizations, which could ultimately help Nova Scotia’s precarious health system better prepare to treat the consequences of poor air quality.

‘It’s kind of this perfect storm of our quality changing, more and more people living with lung disease, and then our health-care system that’s not able to accommodate them in these crisis moments,” she says.

“We want to be able to see whether those are resulting in more hospitalizations to also help the health-care system in anticipating what kind of resources they’re going to need as these changes are happening at a more rapid scale.”

Meanwhile, having additional information could help people dealing with lung conditions, including asthma and COPD, respond when there is a potential climate impact on lung health. That would support a kind of advance planning Tracy Cushing says she advises for her patients in times of increased climate impacts, from avoiding outdoor exercise and wearing an N95 mask, to preparing emergency medications in case they’re evacuated.

“Stress is a really big factor for anybody with lung disease,” she says, and people with COPD in particular may be dealing with fewer resources, as the disease is associated with poverty. “Having that backup plan in place … can help them have a sense of feeling a bit more in control.”