WARNING: This story contains details of female genital mutilation/cutting

Shamsa Sharawe was six years old when she became convinced her family was going to kill her.

“It felt so violent and so … just horrific,” she said. “I just thought, why? Like, if you’re not trying to end my life, why would you do this?”

In a viral TikTok with over 11 million views, Sharawe retells the moment she was a victim of female genital mutilation, a practice that was normalized and celebrated in the Somalian village where she was born.

In the video, she holds up a white rose and a razor, pinching and slicing off the petals. Then, she roughly stitches the remnants together.

“The feeling of being sewn alive, awake, is something I will never be able to describe,” said Sharawe, who now lives in the U.K., just north of London.

Sharawe was a victim of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), what the World Health Organization describes as “the partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.” It may include cutting the clitoris, and the removal or stitching together of the labia.

Beyond excruciating pain, severe bleeding and risk of infection or death, long-term physical and psychological complications often occur.

A UNICEF update shows there are about 230 million victims of female genital mutilation worldwide. An estimated four million girls are subjected to the practice every year, primarily in African countries, followed by Asia and the Middle East, but survivors may live anywhere.

Survivors and activists alike are pushing for better support for a community they say is vastly underserved, especially for those who live in countries where FGM/C is not a traditional practice. They are asking for access to reconstructive surgeries, better mental health services, and more thorough education for health-care professionals, both in Canada and abroad.

“[People] see this as, naively, something happening just on the continent of Africa, which is absolutely not true,” said Alisa Tukkimaki, the national director of the End FGM Canada Network.

Increase in reported victims

Sharawe’s grandma took her to be cut, but she said her family didn’t have malicious intent.

“These women have been programmed and brainwashed into continuing this practice, even though they are survivors themselves,” she said in an interview with CBC.

No religious text promotes or condones FGM/C and it’s widely recognized as a human rights violation. Even so, there’s been a 15 per cent global increase in reported victims since 2016.

In areas where over 90 per cent of girls and women aged 15 to 49 have undergone FGM/C, like Somalia, Guinea and Djibouti, the procedure is engrained within many of their cultures. Sharawe said girls in her village who did not undergo FGM/C were bullied and excluded from society.

“They’ve made it seem like it’s this amazing thing and you’re going to be respected and loved,” the 31-year-old activist said. “And somehow whatever needs to be removed is dirty.”

Sharawe moved to the U.K. in 2001 when her family fled from Somalia’s civil war.

But, there was one thing she couldn’t escape.

“My body couldn’t handle it when I was a child, and my body could not handle it even as an adult,” she said, describing how the chronic pain from her FGM/C was so debilitating that it hurt to sit down, or even wear underwear.

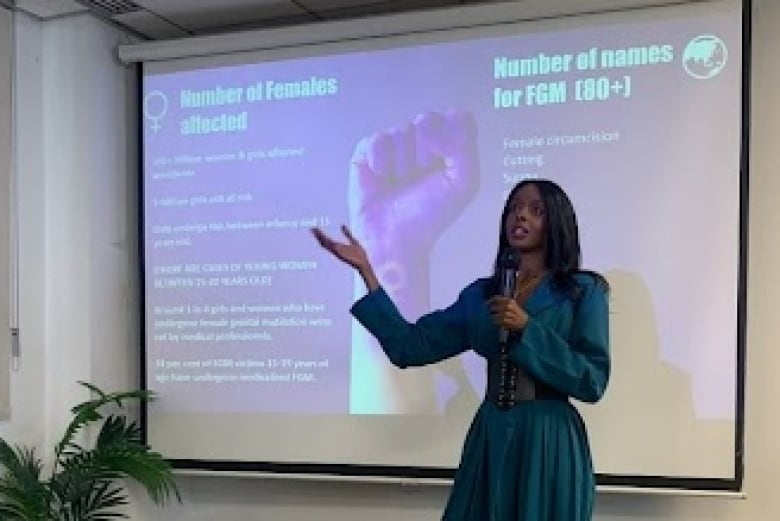

Shamsa Sharawe, 31, was a victim of female genital mutilation as a child in the Somali village where she was born. Now living in the U.K., she recently paid to have reconstructive surgery in Germany, and advocates to have more supports available for survivors.

Reconstructive surgeries not available in the U.K.

Sharawe experienced a variation of FGM/C where her clitoral glans, labia majora and labia minora were removed. Then, the remaining skin was sewn together, leaving a pin-sized hole at the vaginal opening.

“My whole entire life, I felt less than a woman,” she said. “I felt half of a woman.”

After years of health complications, another survivor told her about a type of surgery that reduces pain and allows for increased feeling in the clitoris.

Dr. Dan mon O’Dey pioneered this microsurgery. It involves widening the vaginal opening to normal conditions, and the entire vulva is reconstructed, including the labia. The nerves from the origin of the clitoris are freed from scarring and cysts.

“The tip is recreated,” said O’Dey, the founder and director of the Center for Reconstructive Surgery of Female Gender Characteristics at Luisenhospital in Aachen, Germany.

“The nerves can sprout out from within, into the tissue,” he added.

O’Dey said he performs as many as four of these surgeries per week and there’s a waiting list of up to a year and a half to receive one of his surgeries. He said he’s operated on FGM/C survivors who have travelled from all over the world, but mainly from Europe.

Sharawe spent months raising the money through GoFundMe to afford the procedure, but she’s still in debt after other related expenses. She had surgery in December 2023.

“I’m happy with the way that it looks, with the functionality of it,” Sharawe said. “I tested the motor out, and it works perfectly.”

Sharawe said she partially had surgery to “prove a point” to the British government, trying to show that even though FGM is illegal and not traditionally practised in the U.K., there are still survivors who live in the country. Support systems, she said, like access to reconstructive surgeries, should be in place.

There isn’t data available of the number of FGM/C survivors in the U.K. The closest estimate was published by the National Health Service England’s most recent FGM/C report. It shows that nearly 38,000 women and girls who had experienced FGM/C have been seen at the NHS “where FGM was relevant to their attendance” from April 2015 to March 2024.

Survivors in Canada lack support, says doctor

Reconstructive surgeries are also available in Canada in some form.

Dr. Angela Deane is an obstetrician, gynecologist and surgeon who works at the North York General Hospital in Toronto. While she uses a different technique than O’Dey, her procedures also may include clitoral reconstructive surgery.

In a survey Deane conducted amongst Canadian health-care professionals published in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, she found that over 90 per cent reported they had not received adequate training about FGM/C.

“The impacts of female genital cutting are wide and variable and very personal,” said Deane, who is also an assistant professor at the University of Toronto.

“And so it’s really important that while we’re advocating for more surgical care, that actually we need people that are well versed in just knowing how to talk about the issue from a medical perspective, and especially from the mental health perspective.”

While it’s difficult to track due to FGM/C’s culturally sensitive nature, there is evidence that many survivors reside in Canada, where it is also illegal. Sharawe said she has family members living in the country who have experienced FGM/C.

Canada has significant populations of diaspora communities from areas where FGM/C has traditionally been performed. Statistics Canada states that approximately 94,900 to 161,400 women and girls in the country may have experienced FGM/C, or be at risk of experiencing it in the future.

“It’s a massive global issue that Canada, and our people that live within Canada, have been impacted by,” Deane said.

Eliminating FGM/C through education and awareness

Sharawe said she consistently still gets asked by medical professionals if she’s going to put her 10-year-old daughter through FGM/C.

“I received education, I managed to reprogram my mind,” she said.

“I said no when she was five. I said no when she was six. I said no when she was seven,” she added. “How long are you going to criminalize me?”

FGM/C is a layered issue, but education is one way to eliminate it, UNICEF states. Increased education for children at risk for FGM/C may create safe spaces to foster discussions about the dangers associated with the practice and the right to consent.

Further teachings for medical professionals would additionally create more services in order to properly treat survivors of FGM/C.

“We have to protect the next generation,” Sharawe said. “If we don’t do that, we are just as guilty as the person holding the blade.”