But, what is it, where did it come from and how can the world deal with the threat, which inevitably raises the spectre of pandemics past such as COVID-19 and the early spread of HIV infections?

Here’s what you need to know:

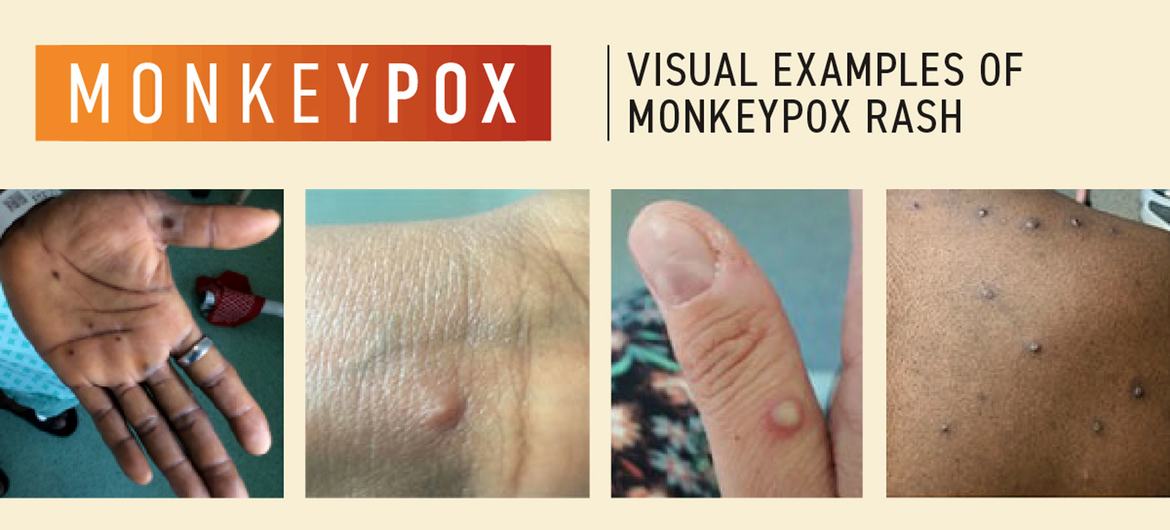

Mpox lesions often appear on the palms of hands. (file)

What is mpox?

Formerly known as monkeypox, the viral disease can spread between people, mainly through close contact, and occasionally from the environment to people via objects and surfaces that have been touched by a person with mpox.

Originating in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1970, mpox was neglected there, according to WHO.

“It is time to act decisively to prevent history from repeating itself,” said Dimie Ogoina, who chairs the International Health Regulations’ Emergency Committee, which advises WHO on such matters.

Endemic in central and West Africa, the infectious disease later caused a global outbreak in 2022, leading to a WHO public health emergency in July as it became a multi-country outbreak.

Following a series of consultations with global experts, WHO has begun using a new preferred term “mpox” as a synonym for monkeypox. Find out more about that decision here.

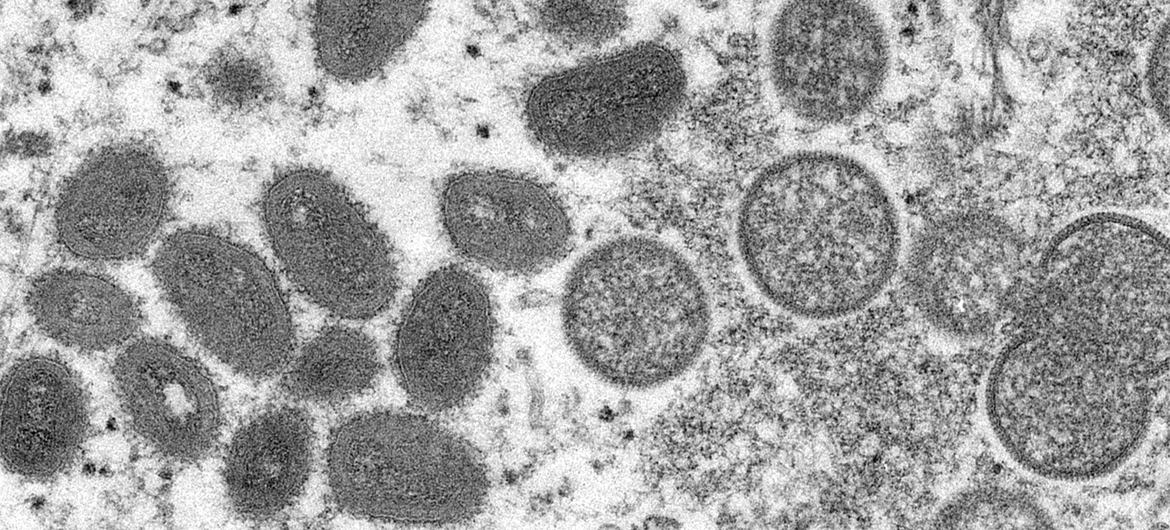

Mpox is similar to the eradicated smallpox virus. (file)

What are the symptoms?

Common symptoms of mpox include a rash lasting for two to four weeks, which may be started with or followed by fever, headache, muscle aches, back pain, low energy and swollen lymph nodes.

The rash looks like blisters and can affect the face, palms of the hands, soles of the feet, groin, genital and/or anal regions, mouth, throat or the eyes. The number of sores can range from one to several thousand.

People with mpox are considered infectious at least until all their blisters have crusted over, the scabs have fallen off and a new layer of skin has formed underneath, and all lesions on the eyes and in the body have healed. Typically this takes two to four weeks. Reports show that people can be re-infected after they’ve had mpox.

People with severe mpox may require hospitalisation, supportive care and antiviral medicines to reduce the severity of lesions and shorten time to recovery.

WHO continues to work with patients and community advocates to develop and deliver information tailored to communities affected by monkeypox.

How does mpox spread?

Human to human: Touching, sex and talking or breathing close to someone with mpox can generate infectious respiratory particles, but more research is needed on how the virus spreads during outbreaks in different settings and conditions, says WHO.

What scientists do know is that it is also possible for the virus to persist for some time on clothing, bedding, towels, objects, electronics and surfaces that have been touched by a person with mpox. Someone else who is in contact with these items may become infected without first washing their hands before touching their eyes, nose and mouth.

The virus can also spread during pregnancy to the fetus, during or after birth through skin-to-skin contact, or from a parent with mpox to an infant or child during close contact.

Although getting mpox from someone who is asymptomatic has been reported, there is still limited information on whether the virus can be transmitted from someone with the virus before they get symptoms or after their lesions have healed.

Humans to animals: Since many species of animals are known to be susceptible to the virus, there is the potential for spillback of the virus from humans to animals in different settings.

People who have confirmed or suspected mpox should avoid close physical contact with animals, including such pets as cats, dogs, hamsters and gerbils, as well as livestock and wildlife.

Animals to humans: Someone who comes into physical contact with an animal which carries the virus, such as some species of monkey – or a terrestrial rodent like a tree squirrel – may also develop mpox. Such exposure can occur through bites or scratches, or during activities such as hunting, skinning, trapping or preparing a meal. The virus can also be caught through eating contaminated meat which is not cooked thoroughly.

A health worker checks on a two-year-old being treated for mpox north of Goma, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Can it be fatal?

Yes, for a small minority. Between 0.1 per cent and 10 per cent of people who have become infected with mpox, have died.

It is important to note that death rates in different settings may differ due to several factors, such as access to health care and underlying immunosuppression, including because of undiagnosed HIV or advanced HIV, according to the UN health agency.

In most cases, the symptoms of mpox go away on their own within a few weeks with supportive care, such as medication for pain or fever, but, in some people, the illness can be severe or lead to complications and eventual death.

Newborn babies, children, people who are pregnant and people with underlying immune deficiencies – such as from advanced HIV – may be at higher risk of more serious mpox disease and death.

A single-dose of the mpox vaccine.

Is there a vaccine?

Yes. The UN health agency recommends several vaccines for use against mpox. However, mass vaccination, which rolled out during the COVID-19 global pandemic, is not currently recommended.

Many years of research have led to the development of newer and safer vaccines for the now eradicated disease smallpox. Some of these vaccines have been approved in various countries for use against mpox.

At present, WHO recommends use of MVA-BN or LC16 vaccines, or the ACAM2000 vaccine when the others are not available.

Only people who are at risk of exposure to mpox should be considered for vaccination, according to WHO. Travellers who may be at risk based on an individual risk assessment with their healthcare provider, may wish to consider vaccination.

One of the ways to prevent mpox from spreading is washing your hands after touching contaminated surfaces.

How can you prevent mpox?

Cleaning and disinfecting surfaces or objects and cleaning your hands after touching surfaces or objects that may be contaminated can help prevent transmission.

The risk of getting mpox from animals can be reduced by avoiding unprotected contact with wild animals, especially those that are sick or dead, including their meat and blood.

In countries where animals carry the virus, any food containing animal parts or meat should be cooked thoroughly before eating.

Learn more about mpox here.