The sheer scale of the U.S. bird flu outbreak is hard to fathom.

More than 100 million farmed birds have been infected with H5N1 since 2022, followed by roughly 170 herds of dairy cows, along with virus detections in more than 200 other mammals — humans included.

Recently, a handful of farm workers in Colorado were infected, marking the country’s first human outbreak: Six confirmed cases are linked to culling efforts at one poultry farm, and at least one likely case is tied to culls at another nearby facility. And while the spread may have been chicken-to-human, the virus strain is similar to the form of bird flu tearing through dairy farms across more than a dozen states.

The country’s total human infection tally, of less than a dozen confirmed cases since 2022, pales in comparison to the staggering case counts among poultry and livestock. There haven’t been any farm worker deaths, and no cases linked to dairy farms have popped up yet in Canada, either.

Yet this new, unusual cluster of human H5N1 cases may be a harbinger of looming challenges to come, all while the broader U.S. outbreak could be surging out of control.

The timing is far from ideal, several scientists told CBC News, with farm worker infections ticking up mere months before the return of the usual flu season, and the fall migration of millions of wild birds — giving this globetrotting virus countless more opportunities to evolve.

“We are looking at, potentially, a huge outbreak that is still expanding, and still growing, and that is not containable,” warned virologist Angela Rasmussen, a researcher with the University of Saskatchewan’s Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization.

“And that increases the risk of more and more human cases, which in turn increases the risk that this virus will become better adapted to humans.”

Mild infections, no onward transmission

Officials first announced the discovery of several farm worker infections back on July 14, all linked to large-scale culling efforts involving H5N1-infected birds on an egg farm in Colorado.

While there aren’t signs of onward human-to-human transmission, sequencing from one of those cases showed the strain is closely related to the virus spreading in dairy cows, which features previously-documented adaptations to mammals, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention noted in a recent update.

More reassuring? So far, all the human cases in the U.S. have been mild infections, despite high H5N1 case fatality rates reported globally over the last two decades. Some farm workers in the Colorado cluster had traditional flu symptoms of fever and cough, while others experienced conjunctivitis, suggesting the virus may have snuck in through their exposed eye membranes rather than through the body’s respiratory channels.

But given the small number of known human infections in the U.S. to date, and the unusual transmission patterns that don’t mimic how this virus would actually spread person-to-person, “we should put no stock at all on what we’re seeing in terms of severity,” noted McMaster University influenza researcher Matthew Miller, the director of the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research.

Virus mashup ‘could create a whole new beast’

If human infections do keep rising into the fall, in Colorado or beyond, experts say the timing would be advantageous to a virus that’s already proven quite adept at striking a wide variety of species. And a host of factors, several scientists agreed, may provide opportunities for H5N1 to better adapt to infect and harm more human hosts.

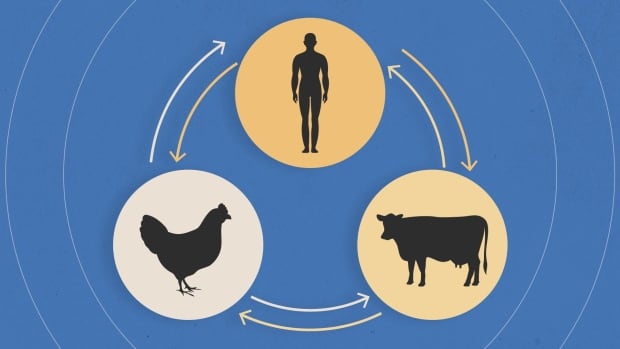

For one thing, the dovetailing of heightened human H5N1 circulation and the return of seasonal flu strains could have dire consequences, said virologist Tom Peacock, a fellow with the Pirbright Institute, a U.K.-based research and surveillance centre for zoonotic viruses.

“Suddenly, some of these workers who are getting exposed and infected [with H5N1] have a chance of being infected with seasonal flu. And then the poultry or dairy worker is acting as the mixing vessel.”

Those scenarios would give the virus a chance to mash up its genetic makeup with other flu strains, potentially allowing it to mix-and-match characteristics that could sharpen its ability to transmit person-to-person. It’s a process known as reassortment, and influenza viruses are particularly adept at it.

That genetic reassortment, Miller said, “could create a whole new beast.”

There’s also a heightened risk of other farms becoming infection sites in the months ahead, Peacock warned, given H5N1’s penchant for spilling between species.

Already, mounting evidence suggests heightened mammal-to-mammal transmission is taking place even now. A peer-reviewed paper in Nature, published online Wednesday, looked at genomic sequencing for a host of infected species, including cows, birds, domestic cats and a raccoon from impacted farms.

The research team found evidence of both “multidirectional interspecies transmissions” and “efficient cow-to-cow transmission” after seemingly healthy cows from an affected farm were transported to a facility in a different state.

The possibility of onward spread into pig populations in the months ahead is one of Peacock’s biggest concerns, since swine “have a lot of viruses circulating within them that are derived originally from human seasonal viruses.”

“This is how pandemics happen: The mixing of seasonal viruses with avian viruses or novel viruses,” he said.

The 2009 swine flu pandemic is one of the most familiar, resulting from a mashup of bird, pig and human forms of influenza A.

Miller agreed the possibility of that happening on U.S. pig farms is a rising threat. “We’re not doing enough proactive surveillance in those settings right now,” he added. “It’s a little frustrating.”

On top of that, scientists expect another wave of migrations could further fuel H5N1’s global spread, with millions of wild birds set to fly along north-south avian superhighways in the months ahead.

“There are tremendous opportunities [for H5N1] to recombine in new and unexpected ways as these waves of migration take place,” Miller said.

Human spread remains hazy

All those added variables could make the U.S. bird flu outbreak even tougher to contain, heightening the risk to humans and putting other countries — including Canada — on alert.

“Eventually, if this continues, we will have viruses emerging that are better adapted to humans. What that’s going to look like in practice, and whether that causes a pandemic, we don’t know,” said Rasmussen.

Complicating matters? The full extent of H5N1’s human spread in the U.S. still remains hazy.

A recent serology study in Michigan, which involved testing blood samples from 35 farm workers who’d spent time around infected dairy cows, didn’t find evidence of prior infections — suggesting there might not be symptomless human infections flying under the radar.

But it’s just one small study, from just one health department.

Colorado, meanwhile, is ramping up surveillance efforts to combat the rampant spread of the virus, including a mandatory order on Tuesday for weekly bulk milk-tank testing at dairy farms.

Yet data from other states remains thin thanks to patchwork testing efforts mired by bureaucratic roadblocks, which means the U.S. is likely missing both animal and human cases, experts have warned for months.

“It’s really hard to tell if Colorado was genuinely in a worse state than a lot of other states, or it’s just testing and finding stuff,” said Peacock. “This is one of the major issues with this outbreak: We don’t really have any idea.”

Calls for farm worker vaccinations

Meanwhile, Rasmussen says there’s “not really clear decisive action being taken” to clamp down on animal or human infections.

Alongside the need for heightened testing and surveillance efforts, she said H5N1 vaccination strategies targeting at-risk farm workers are another tool the U.S. should consider before the situation spirals out of control.

So far, however, the CDC has not recommended vaccinations for any livestock workers.

Canada, Rasmussen said, should also remain vigilant, despite no known farm worker infections or any signs of the virus appearing in the country’s milk supply. (Only one human case of H5N1 has ever been reported in Canada. The individual died from bird flu back in 2014 following a trip to China, where they likely got infected.)

A look at CBC News coverage of H5N1’s spread across the globe between 2004 and 2024, from early bird flu outbreaks in Asia to the ongoing spread of the virus in dairy cows.

Other countries are taking a different approach. In late June, Finland became the first to pursue proactive bird flu vaccination for any adults “who are at increased risk of contracting avian influenza due to their work or other circumstances.”

The U.S. should take note, Rasmussen said, as sweltering temperatures in Colorado limited workers’ ability to wear protective equipment while they were killing infected poultry — leaving them vulnerable to catching the virus.

With more hot months ahead, and untold numbers of virus-carrying farm animals across the country, that scenario could easily happen again.

“It’s a mistake not to offer some limited vaccination,” Rasmussen said. “Especially given the current situation.”