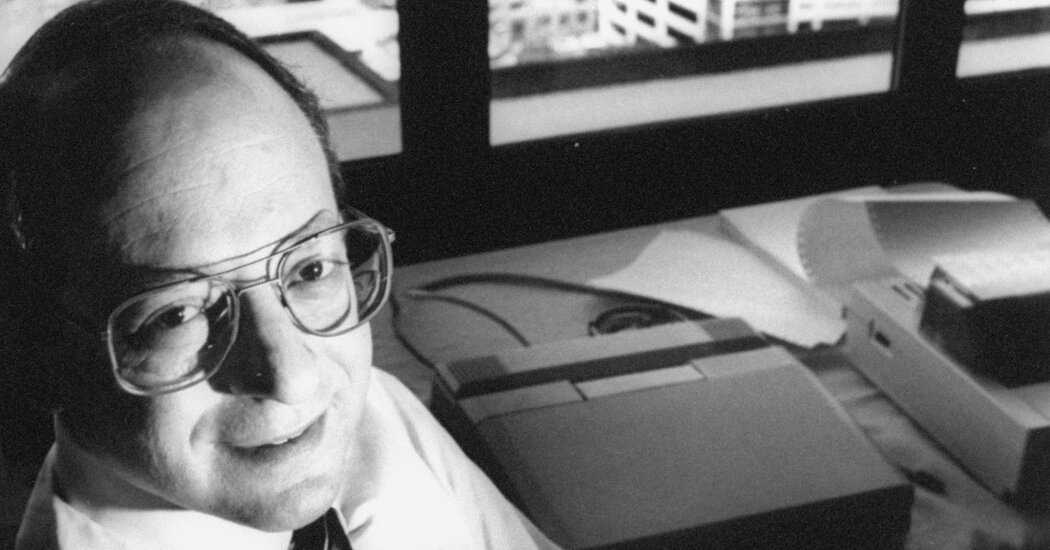

Bennett Braun, a Chicago psychiatrist whose diagnoses of repressed memories involving horrific abuse by devil worshipers helped to fuel what became known as the “satanic panic” of the 1980s and ’90s, died on March 20 in Lauderhill, Fla., north of Miami. He was 83.

Jane Braun, one of his ex-wives, said the death, in a hospital, was from complications of a fall. Dr. Braun lived in Butte, Mont., but had been in Lauderhill on vacation.

Dr. Braun gained renown in the early 1980s as an expert in two of the most popular and controversial areas of psychiatric treatment: repressed memories and multiple personality disorder, now known as dissociative identity disorder.

He claimed that he could help patients uncover memories of childhood trauma — the existence of which, he and others said, were responsible for the splintering of a person’s self into many distinct personalities.

He created a unit dedicated to dissociative disorders at Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center in Chicago (now Rush University Medical Center); became a frequently quoted expert in the news media; and helped to found the what is now the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation, a professional organization of over 2,000 members today.

It was from that sizable platform that Dr. Braun publicized his most explosive findings: that in dozens of cases, his patients discovered memories of being tortured by satanic cults and, in some cases, of having participated in the torture themselves.

He was not the only psychiatrist to make such a claim, and his supposed revelations keyed into a growing national panic.

The 1980s saw a vertiginous rise in the number of people, both children and adults, who claimed to have been abused by devil worshipers. It began in 1980 with the book “Michelle Remembers,” by a Canadian woman who said she had recovered memories of ritual abuse, and spiked following allegations of abuse at day care centers in California and North Carolina.

Elements of pop culture, such as heavy metal music and the role-playing game Dungeons and Dragons, were looped in as supposed entry points for cult activity.

Such stories were fodder for popular TV formats that reveled in the salacious, including talk shows like “Geraldo” and newsmagazines like “Dateline,” which broadcast segments that promoted such claims uncritically.

The psychiatric profession bore some responsibility for the growing panic, with respected researchers like Dr. Braun giving it a gloss of authority. He and others ran seminars and distributed research papers; they even gave the phenomenon a quasi-medical abbreviation, S.R.A., for satanic ritual abuse.

Dr. Braun’s inpatient unit at Rush became a magnet for referrals and a warehouse for patients, some of whom he kept medicated and under supervision for years.

Among them was a woman from Iowa named Patricia Burgus. After interviewing her, Dr. Braun and his colleague, Roberta Sachs, claimed that she was not only the victim of satanic ritual abuse, but was also herself a “high priestess” of a cult that had raped, tortured and cannibalized thousands of children, including her two young sons.

Dr. Braun and Dr. Sachs sent Mrs. Burgus and her children to a mental health facility in Houston, where they were held apart for nearly three years with minimal contact with the outside world.

By then Mrs. Burgus, heavily medicated, had come to believe the doctors, telling them she recalled torches, live burials and eating the body parts of up to 2,000 people a year. After her parents served her husband meatloaf, she had him get it tested for human tissue. The tests came back negative, but Dr. Braun was not convinced.

Dr. Braun kept other patients under similar conditions at Rush or elsewhere. He persuaded one woman to have an abortion because, he convinced her, she was the product of ritualistic incest; he persuaded another to undergo tubal ligation to prevent having more children within her supposed cult.

The satanic panic began to wane in the early 1990s. A 1992 F.B.I. investigation found no evidence of coordinated cult activity in the United States, and a 1994 report by the National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect surveyed over 12,000 accusations of satanic ritual abuse and found that not a single one held up under scrutiny.

“The biggest thing was the lack of corroborating evidence,” Kenneth Lanning, a retired F.B.I. agent who wrote the 1992 report, said in a phone interview. “It’s the kind of crime where evidence would have been left behind.”

Many people distanced themselves from their earlier enthusiasms; in 1995, Geraldo Rivera apologized for his episode covering the falsehood. However, even in 1998, “Dateline” ran an episode on NBC claiming to show widespread satanic activity in Mississippi.

Mrs. Burgus sued Rush, Dr. Braun and her insurance company over claims that he and Dr. Sachs had implanted false memories in her head. They settled out of court in 1997 for $10.6 million.

“I began to add a few things up and realized there was no way I could come from a little town in Iowa, be eating 2,000 people a year, and nobody said anything about it,” Mrs. Burgus told The Chicago Tribune in 1997.

A year later Dr. Braun’s unit at Rush was shut down, and the Illinois medical licensing board opened an investigation into his practices. In 1999, he received a two-year suspension on his license — though he did not admit wrongdoing.

Bennett George Braun was born on Aug. 7, 1940, in Chicago, to Thelma (Gimbel) and Milton Braun, a professor of orthodontics at Loyola University. He graduated from Tulane University with a bachelor’s degree in psychology in 1963 and earned a master’s in the same subject in 1964. He received his medical degree from the University of Illinois in 1968.

Dr. Braun was married three times. His marriages to Renate Deutsch and Mrs. Braun both ended in divorce. His third, to Joanne Arriola, ended in her death. He is survived by five children and five grandchildren.

After temporarily losing his medical license in Illinois, Dr. Braun moved to Montana, where he received a new license in that state and opened a private practice.

But in 2019, one of his patients, Ciara Rehbein, sued him for overprescribing medication that left her with a permanent facial tic. She also filed a complaint against the Montana Board of Medical Examiners for allowing him a license, despite knowing his past.

Dr. Braun lost his license to practice medicine in Montana in 2020.