Claire Hafner’s chin is tucked in protectively behind her gloves. Just above them, her eyes are laser-focused, looking for an opening. Her arms shoot out like twin pistons, forcing the solid teen powerhouse she’s sparring with to retreat against the ropes.

At 46, the Edmonton-based boxer is mulling over retirement but wants a Canadian title before she throws in the towel.

“It’ll be hard to hang up the gloves without checking that box,” she said.

That decision hangs largely on what a team of researchers in Las Vegas find when she meets up with them for exhaustive annual testing on her brain health.

Hafner is one of 17 Canadian athletes participating in a landmark study of the effects of head trauma on 900 living athletes, mostly from combat sports.

Only about 100 of the participants are women, so Hafner’s brain may provide insights to help future women athletes, patients with neurodegenerative conditions, survivors of intimate partner violence and soldiers with head trauma.

Claire Hafner is one of 17 Canadian athletes participating in a study on the effects of head trauma on 900 living athletes, mostly from combat sports. She calls it a ‘once in a lifetime opportunity.’

The Professional Fighters Brain Health Study started in 2011 at the Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas with just a few dozen athletes and a goal of examining the long-term effects of head trauma on athletes and its possible links to neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s.

The cumulative research has generated numerous peer-reviewed papers on head trauma, including work on blood biomarkers of repetitive head injuries, a review of the impacts on male and female fighters’ brains and changes in the brains of fighters after they retire.

The data is collected through private annual assessments of participating athletes. Those tests also provide each individual athlete with information about any deterioration of their memory, reaction times, balance or brain tissue.

A battery of tests

“Boxing is a sport where you volunteer to be punched in the head. So I think there’s less sympathy around head trauma,” Hafner said.

After years of sparring and taking hits, she worries about the short term and cumulative effects on her brain, but usually not in the heat of the moment.

“I’m in the ring and I don’t even realize I get hit. Like I have to watch my video back and be like, ‘Oh, I took a big one,'” she said.

During her annual visits to the centre, which began in 2020, she undergoes a two-hour series of computerized tests and fills out a self-assessment on her moods and emotional wellbeing. Her blood is sent to the lab to look for increases in protein markers that could indicate head trauma. They are many of the same markers found in people with conditions like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

This time around, her results will determine whether she risks another year in the ring.

Women an important part of the study

One of the main focuses of the study, according to the chief researcher Dr. Charles Bernick, is to empower athletes to make informed decisions about their careers and when it might be time to tap out.

It also looks for tell-tale signs of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE, a degenerative condition linked to repeated head trauma which can only be diagnosed after death.

Christine Ferea, who is among the 900 athletes participating in a study on the effects of head trauma, hopes the research helps settle debates happening in women’s combat sports — like how many rounds there should be and how long they should last.

Using blood tests and MRIs, researchers look for some of the characteristics associated with the condition with the hope of one day being able to diagnose CTE in living athletes and maybe even prevent it from progressing.

Last year, the first case of CTE was diagnosed in a female athlete — an Aussie rules footballer.

Bernick says that having women participate in the study is important, because there are gaps in understanding the long-term effects of head impacts on women “whether that’s in sports or domestic violence or in our military.”

Already, they’ve made some remarkable preliminary findings including that when it comes to long-term effects, women fighters appear to fare better than their male counterparts.

“It doesn’t seem that they’re at a higher risk,” said Bernick. “If we have two groups that are getting hit, and the women are doing better, is there something biological that is protecting them?”

Reigning women’s bare-knuckle boxing world champion Christine “The Misfit” Ferea also signed up for the study, in part for peace of mind.

“It made me feel a little bit safer. So each year I’m going, if I’m not declining, I’m not going to retire,” she said.

Ferea also hopes the research helps settle debates happening in women’s combat sports like how many rounds there should be and how long they should last.

“I think it’s a great thing to have. And especially for the female fighters, we don’t have that research because we haven’t been in combat sports for as long as men,” Ferea said.

The study is also finding evidence that once people with signs of deterioration leave a combat or high impact sport, their blood markers and brain imaging stabilize and that, as a group, they are finding people get better.

“When people are actively exposed to head impacts, it is changing the brain. And once you stop, there is this opportunity for repair,” he said.

‘What’s one more time?’

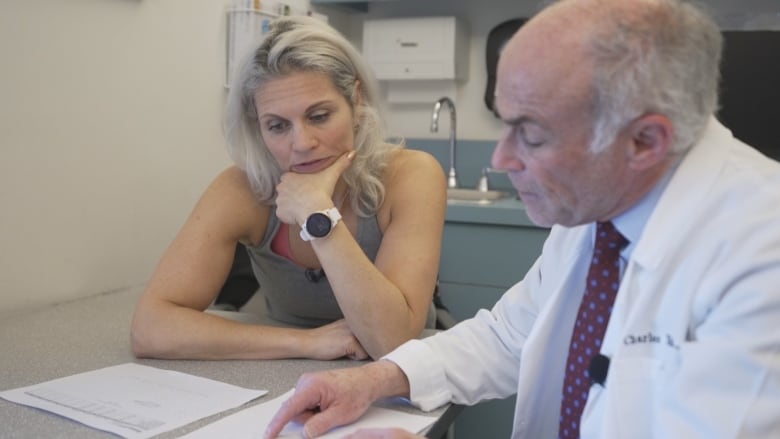

When Hafner gets her test results, it’s good news: “You are superior to most people your age,” according to Bernick.

His assessment of whether or not she should retire is less definitive.

“If you’re asking, are you going to do irreparable harm to do one more fight? Of course not. You know, because all this stuff is just cumulative,” Bernick said during their consultation. “If you’ve achieved what you’ve wanted to achieve. Yeah, it’s probably better for your brain not to get hit.”

After her results she said it is “a hundred times more tempting” to stave off retirement.

“You get good news and it kind of momentarily blots out the risks because you’re like, ‘Ooh, I’ve been risking it all for these years. And hey, it’s been good. Like there’s nothing awful yet so what’s one more? What’s one more time?'” she said.

“I want to stay in the ring.”