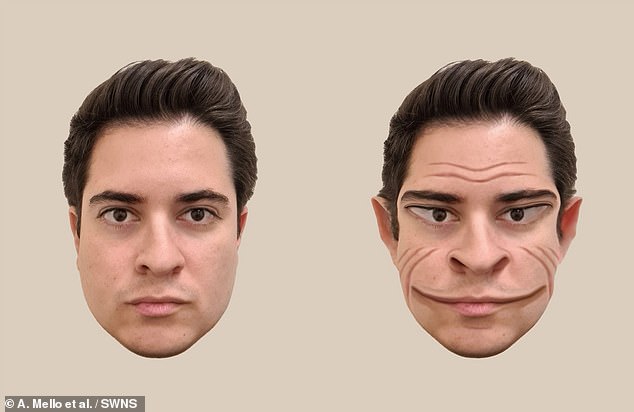

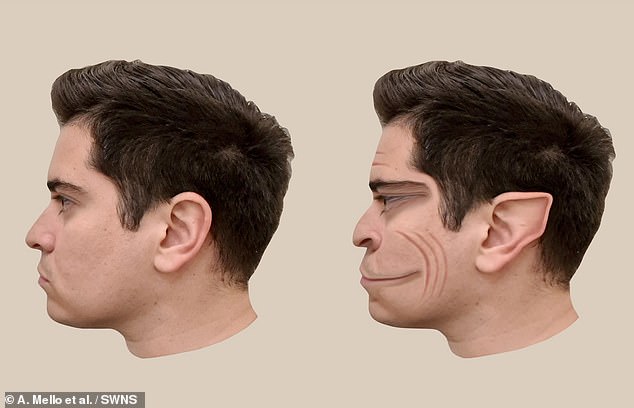

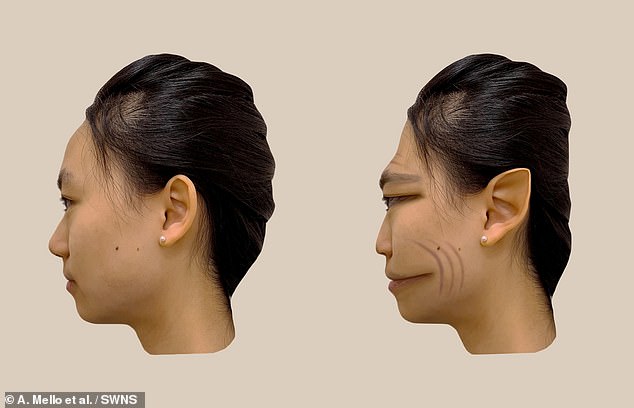

Their distorted features would be the stuff of nightmares for many.

But this is what everyday people look like to people with a rare condition called prosopometamorphopsia (PMO).

For the first time, researchers have been able to create realistic clinical pictures based on a patient’s experience of the facial distortions experienced by an individual with the ultra-rare condition.

‘Prosopo’ comes from the Greek word for face ‘prosopon’ while ‘metamorphopsia’ refers to perceptual distortions.

The pictures were created by Dartmouth College based on a 58-year-old man with PMO.

The pictures were created by Dartmouth College based on a 58-year-old man with prosopometamorphopsia (PMO). He sees faces without any distortions when they are viewed on a screen and on paper, but he sees distorted faces that appear ‘demonic’ when viewed in-person

Most PMO cases however, see distortions in all contexts, so his case is especially rare and presented a unique opportunity to accurately depict his distortions, according to the findings published in The Lancet

He sees faces without any distortions when they are viewed on a screen and on paper, but he sees distorted faces that appear ‘demonic’ when viewed in-person.

Most PMO cases, however, see distortions in all contexts, so his case is especially rare and presented a unique opportunity to accurately depict his distortions, according to the findings published in The Lancet.

Researchers took a photograph of a person’s face.

They then showed the patient the photograph on a computer screen while he looked at the real face of the same person.

The researchers obtained real-time feedback from the patient on how the face on the screen and the real face in front of him differed, as they modified the photograph using computer software to match the distortions perceived by the patient.

Lead author Antônio Mello said: ‘In other studies of the condition, patients with PMO are unable to assess how accurately a visualization of their distortions represents what they see because the visualization itself also depicts a face, so the patients will perceive distortions on it too.’

Researchers took a photograph of a person’s face. They then showed the patient the photograph on a computer screen while he looked at the real face of the same person

The researchers obtained real-time feedback from the patient on how the face on the screen and the real face in front of him differed, as they modified the photograph using computer software to match the distortions perceived by the patient

As this patient doesn’t see distortions on a screen, the researchers were able to modify the face in the photograph, and the patient could accurately compare how similar his perception of the real face was to the manipulated photograph.

‘Through the process, we were able to visualize the patient’s real-time perception of the face distortions,’ added Mello.

The co-authors state that some of their PMO participants have seen health professionals and were wrongly diagnosed them with other health conditions, such as psychosis.

They hope that by publishing this case, they will raise awareness of the condition.

Brad Duchaine, a professor of psychological and brain sciences and principal investigator of the Social Perception Lab at Dartmouth, said: ‘We’ve heard from multiple people with PMO that they have been diagnosed by psychiatrists as having schizophrenia and put on anti-psychotics, when their condition is a problem with the visual system.’