When Dan Shire’s heart stopped beating in 2016, it led to a race against time to save his life.

Shire’s wife heard him struggling to breathe in the middle of the night. Then she ran to the phone to call 911, started CPR, and waited minute-by-painful-minute for first responders to show up.

Once paramedics arrived at the couple’s Pickering, Ont., home, they used a defibrillator on Shire four times, then tried a potent medication in an attempt to restart his heart.

That drug, epinephrine — also called adrenaline — is given intravenously every three to five minutes, up to an average of six milligrams. It stimulates blood flow by squeezing the blood vessels, which can, in some cases, help get someone’s heart beating again.

But researchers worry there’s a dangerous ripple effect: When you save someone’s heart, you can hurt their brain. Studies suggest higher doses of epinephrine might actually cause neurological damage.

In Shire’s case, he survived his episode of cardiac arrest and now leads a largely normal life. But the 67-year-old does have cognitive impacts such as short-term memory issues and some difficulty with complex tasks like driving. He’s not sure how much of that is from his heart stopping — cutting off oxygen to his brain for the better part of 16 minutes — or the dose of epinephrine he was given.

To give cardiac arrest patients the best chance at not only survival, but also a high quality of life, Canadian researchers have launched a massive, years-long trial to find the “sweet spot” for epinephrine usage.

“There could be a tendency that [first responders] are erring on the side of giving you as aggressive a treatment as possible to save your life in that moment,” said Shire.

“A month later, you might find yourself in the position where you had too much epinephrine, and now have problems with cognitive outcomes.”

Trial will include multiple provinces

Dubbed EpiDose, the randomized controlled trial involves paramedic teams in B.C., Ontario, and eventually more provinces. Each time those teams encounter a patient with cardiac arrest, they’ll randomly provide either a higher or lower dose of epinephrine.

Then researchers will track the results, not just to see which lives are saved, but to find out about their brain function afterwards.

It’s the latest in a set of ongoing studies on epinephrine from a research team co-led by Dr. Steve Lin, the interim chief of emergency medicine at St. Michael’s Hospital, a part of Unity Health Toronto.

The team is hoping to include data on nearly 4,000 randomly-selected patients — a process that could take five to six years.

The drug epinephrine — or adrenaline — can increase a person’s chances of survival and full recovery after a cardiac arrest, but the optimal dose isn’t really known. A new study is equipping some paramedics in Ontario and B.C. with different doses of the drug to help determine the answer.

Lin said the researchers are proposing a new “ceiling” for the standard dose, if the results suggest that a lower dose of two milligrams in total works just as well or better than the current standard of six milligrams. His team will then be contacting survivors to see how their bout of cardiac arrest impacted their life, including their later neurological function.

That’s another reason why the trial will take years: Survivors will be few and far between. When it comes to cardiac arrest, most people don’t make it, with only an estimated 10 per cent of patients surviving if their heart stops outside of a hospital.

“Cardiac arrest is the most deadly condition, right?” noted Lin. “It’s when your heart actually stops beating. And if left untreated, patients will certainly die.”

Optimizing the dose

Epinephrine can save lives, he stressed, particularly when it’s used following first-response measures like cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and a defibrillator, which applies an electric charge to help a stopped heart start beating. But Lin is hopeful that a smaller epinephrine dose might optimize outcomes, allowing the medication to help restart the heart without damaging later brain function.

One randomized trial looking at epinephrine use for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, published in 2018 in the New England Journal of Medicine, found the overall rate of survival 30 days later was slightly better in the group given epinephrine — up to an average of close to five milligrams — compared to those given a placebo.

But there were also noticeable differences in the groups’ brain function. Close to a third of those given epinephrine ended up with severe neurological disability, compared to less than 18 per cent in the placebo group.

“There is some evidence that there might be very high doses given that can harm the brain, because you squeeze the blood vessel so much that it starts to decrease blood flow to the brain itself,” Lin said.

“I think we can actually do better.”

When someone goes into cardiac arrest, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR, is one of the best ways to give them a shot at survival. Chris Schmied from St. John’s Ambulance walks health reporter Lauren Pelley through the basic steps.

‘These are really tough calls’

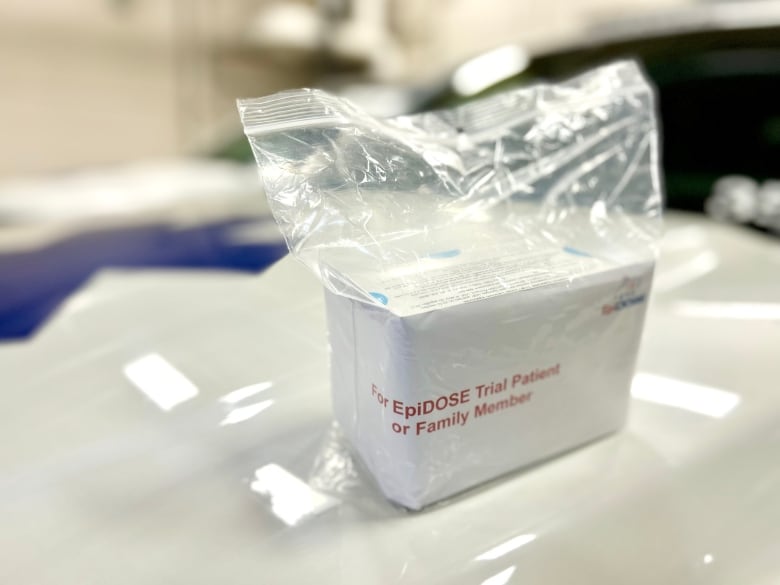

Sitting in the back of an ambulance in Oakville, Ont., longtime Halton Region paramedic Olena Campeau holds up one of the study kits: A white box labeled EpiDose, with no further information on what’s inside. It’s only when paramedics open the kit that they’ll learn which treatment arm a patient is assigned to, Campeau explained.

Halton Region was among the first paramedic teams to sign onto the trial, alongside services in Peel, Toronto, Ottawa and British Columbia Emergency Health Services.

Conducting this kind of research is crucial, but it comes with challenges, she added. Cardiac arrest calls are fast-paced — since every moment counts when it comes to survival rates — and can happen anywhere.

“I attended to a cardiac arrest on a patient at an outdoor climbing wall,” Campeau said. “These are really tough calls for paramedics.”

The patients themselves are also unconscious, which adds another layer of complexity to the EpiDose research since people can’t actually give verbal or written consent to participate.

There’s also no time for paramedics to get a sign-off from someone’s family members, Lin noted, and that’s assuming anyone who knows the patient is even present.

Typically, advance consent from participants is a hallmark of medical studies like this. But since cardiac arrest is so deadly — and concrete research on the ideal epinephrine dose is so lacking — Lin said the team’s research is allowed under strict research ethics guidelines.

Surviving patients, or a deceased patient’s family, will be alerted after the fact, and patient information collected during the trial will also be de-identified and replaced by a unique study number to keep patients’ identities private.

The study was approved by the Sunnybrook Research Ethics Board, which means it meets federal guidelines for ethical research involving humans.

Study could ‘change treatment’ approach globally

Emergency physician Dr. Benjamin Abella, director of the Center for Resuscitation Science at the University of Pennsylvania, said while adrenaline has been a cornerstone of cardiac arrest treatment for many years, it’s never been put to a proper clinical trial.

Animal models, and more recent human data, do suggest the drug improves initial survival rates, he noted — as in simply bringing back someone’s pulse. “But it leads to way more neurological injuries. That has to be really considered in how we approach patients with cardiac arrest.”

The Dose18:33What do I need to know about cardiac arrest?

If someone near you goes into cardiac arrest, your quick actions could help save their life. Dr. Roopinder Sandhu, professor in cardiac sciences at the University of Calgary, shares what you need to know about basic life support and how to prevent cardiac arrest. For transcripts of The Dose, please visit: lnk.to/dose-transcripts. Transcripts of each episode will be made available by the next workday.

Abella, who isn’t involved in the EpiDose trial, welcomed deeper research into how well epinephrine works, given that hundreds of thousands of people across North America experience cardiac arrest in any given year.

“Dosing and timing of epinephrine are both really open questions, and we don’t have the answers,” he said. “I’m old enough to remember a time when dosing for epinephrine was much higher during cardiac arrest in the guidelines than what we do currently. And so that was changed — and it may need to change yet again.”

Lin and Campeau are both optimistic that the EpiDose trial could eventually reshape how paramedics tackle situations where someone’s heart has stopped beating, and even inform global clinical guidelines for how to best use epinephrine.

“We know that this is a crucial study,” Campeau said. “It can change treatment for cardiac patients across Canada, and possibly worldwide.”