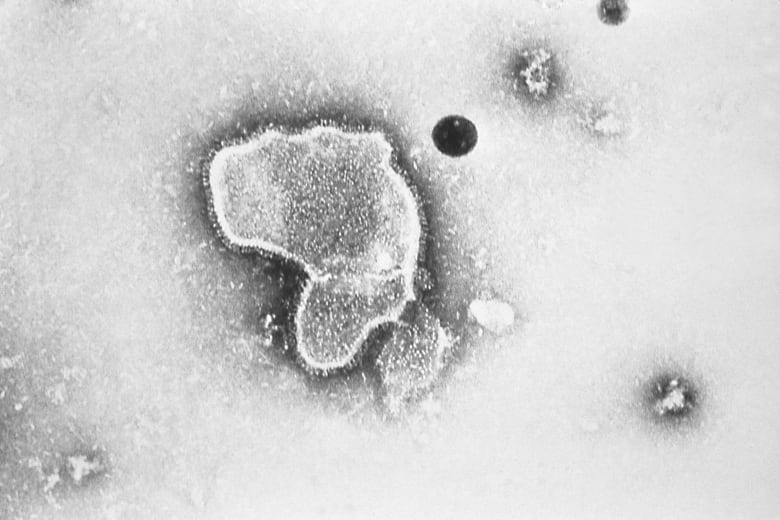

Nearly half of children hospitalized for RSV in Canada’s pediatric hospitals in recent years were under six months of age, a new study has found, calling attention to the need for preventative options to ease the pressure on intensive care units caring for the sickest.

In research published Wednesday in JAMA Network Open, Dr. Jesse Papenburg and his team from the Canadian Immunization Monitoring Program Active (IMPACT) looked at the number and severity of hospital admissions associated with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) at 13 pediatric hospitals, from 2017 to 2022.

Infections in that period resulted in 11,000 hospitalizations, with nearly half — or 5,488 — being children under six months of age. Doctors in other countries, such as the U.S. and Denmark, noticed a similar trend.

Hospitalizations also increased in the most recent year of the study, compared to pre-pandemic times, with nearly a quarter of the kids needing ICU care, like mechanical ventilation.

RSV causes infection of the lungs and the respiratory tract. The virus generally leads to cold-like symptoms, such as runny nose, cough and fever, but it can be severe in some people, including children under two and older adults with pre-existing conditions.

In babies, mucus and other secretions can plug up small airways and make it hard for them to breathe, pediatricians say. They might need oxygen or become dehydrated and need hospitalization.

“Last season … was really incredible in terms of how, across the country, we saw an early and very intense RSV season, with peak levels of activity occurring [in] late October, November and then trailing off,” said Papenburg, one of the study’s senior authors and a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at the Montreal Children’s Hospital.

“RSV typically affects us mostly during the dark months of winter.”

Mom’s ICU scare

Mila Olumogba’s infant son, Adeyemi, spent two weeks in the ICU at CHEO in Ottawa last year, recovering from RSV, when he was only 10 weeks old. One of Olumogba’s older children likely brought the virus home.

Olumogba said she hadn’t even heard of RSV until the baby became lethargic and the normally voracious eater stopped breastfeeding. When he appeared limp and his whole body struggled just to take a breath, Olumogba took him to the emergency department.

When the test came back positive for RSV, he was moved to the ICU, put in an induced coma and was on mechanical ventilation that resembled scuba gear, she recalled.

“The staff kept telling me, it’s gonna get really bad before it gets better and you just need to prepare yourself for that,” Olumogba said.

When Adeyemi’s breathing stopped, Olumogba watched staff resuscitate her baby. “It’s honestly the most traumatic experience that you can go through,” she said.

Prior to infection, doctors planned to offer Olumogba a preventive treatment for Adeyemi, because he was considered to be high risk, born with a small hole in the lower chambers of his heart that’s now closed.

But the boy got RSV before he could receive it.

Treatment options slowly coming online

The study’s authors say their findings suggest preventative RSV treatments starting to roll out for infants may have the greatest potential to reduce serious illness in babies, like Adeyemi, pending cost-effectiveness reviews by the provinces.

There were nearly no hospitalizations for RSV when people stayed home during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. But as public health measures were lifted and people resumed normal life, RSV and other respiratory illnesses in daycares led to many children getting sick at once, Papenburg said.

Researchers were surprised at how RSV peaked at different times across Canada. Quebec was hit hardest and first. At the other end of the season, doctors in the Prairies had to keep treating the sickest kids well into this spring — unlike in previous years.

Featured VideoHealth officials in Canada are preparing for what they say could be a busy season for viruses. Cases of RSV, influenza and COVID-19 are beginning to rise. Dr. Lisa Barrett says it’s time for people to once again become more vigilant.

One way to reduce ICU admissions is to use long-acting monoclonal treatment injections to children considered high risk, such as those born extremely preterm or with heart conditions. But rolling them out effectively will need public health surveillance, experts note.

Pediatricians hope a single-dose treatment called nirsevimab — recently approved by Health Canada for all children under one and for those under two deemed high risk — will protect their youngest patients for a full RSV season.

Another way to protect newborns is by vaccinating during pregnancy, so the antibodies pass to the baby. But Health Canada is currently reviewing approval of such a vaccine.

A seasonal triple threat

Last season was a perfect storm for respiratory illness, said Dr. Rod Lim, medical director for the pediatric emergency department at the Children’s Hospital in London, Ont., who wasn’t involved in the study.

Never in his 20-year career had he seen so many children test positive for multiple respiratory viruses — like influenza, COVID and RSV — all at once, he said

“That’s why there’s such efficient spreaders of viruses that all parents are certainly aware of,” said Lim.

The summer normally offers a reprieve for everyone working in hospitals, Lim noted, but that didn’t happen last season. Finding ICU capacity remains a challenge ahead of this season, on top of paramedic diversions from emergency departments and “prominent” mental health distress among children, he said.

“We have been working short-staffed, even amongst physicians,” Lim said.

Pediatricians suggest parents seek medical attention for any infant under three months of age with a fever. The same is true if a child is clearly having trouble breathing or if there’s a concern about dehydration, like a dramatic decrease in wet diapers, said Lim.

Doctors also treat older children and teens with lung conditions, like cystic fibrosis, that make them vulnerable to RSV infections in their lower respiratory tract.

Since the study was conducted at pediatric hospitals, the authors note the full burden of RSV on kids and teens would likely be even higher if community hospitals are considered. Changes in testing practices, whether RSV was the main reason for the hospitalization, and a lack of detailed data for the initial summers also may have hampered the analysis.