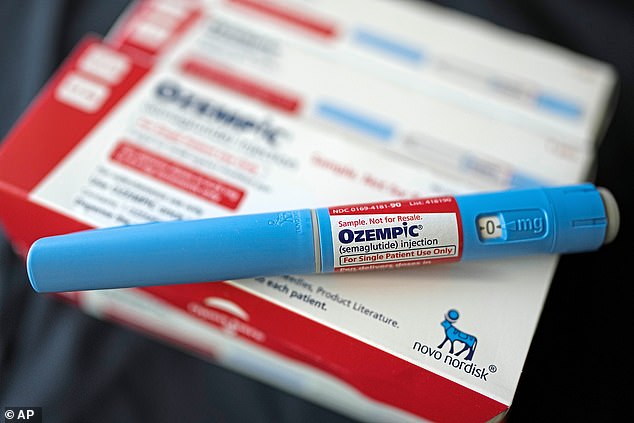

While Ozempic has taken the US by storm for being touted as a magic weight-loss drug, scientists are now curious if it could also be used to treat other health conditions, like alcoholism, drug addiction and even dementia.

The injection of semaglutide, the active drug in Ozempic, is approved for treatment in diabetics to lower blood sugar levels. However, it has soared in popularity as an off-label weight-loss drug, despite a host of nasty side effects.

While people have anecdotally suggested the drug helped them kick undesired long-term habits alongside their binge eating, Ozempic’s powers are being put to the test in human clinical trails for things like alcohol addiction and dementia.

One of the researchers involved in the trials, Kyle Simmons, a professor of pharmacology and physiology at Oklahoma State University, said if the studies’ results are positive, ‘it’s hard to overstate the effect this will have on the field [of addiction medicine].’

Now Ozempic’s powers are being put to the test for things like alcohol addiction and even dementia in human clinical trials

Henry Webb, from North Carolina, finished a two-month course of Wegovy, a drug similar to Ozempic, after hitting his weight goal. In the past, he would consistently have a couple of drinks in the evening, but said: ‘On the medication I had zero desire for that’

Ozempic helps people lose weight by mimicking the GLP-1 hormone, which curbs hunger and slows the rate at which a person’s stomach empties, leaving them feeling fuller for longer.

But experts say it may also reduce the levels of dopamine, or the reward hormone, released in the brain. Cutting levels of this hormone could lead to a decline in the ‘feel good’ element of giving into unhealthy cravings or behaviors.

Professor Simmons is currently leading a trial testing semaglutide’s ability to reduce people’s alcohol intake. An additional separate study is also taking place at the University of Baltimore.

Simmons theorized the drug could be dulling the brain’s reward signaling in a way that means people’s ability to experience pleasure is reduced not just for food, but for everything.

‘If this drug is used by more and more people, if it starts to promote a loss of interest in pleasure more generally, that might not be a great thing, for example, for people who have a history of major depressive disorder,’ he told CNBC.

More research, however, is necessary to understand the effect of semaglutide on the brain, Simmons added.

Christian Hendershot, director of the translational addiction research program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is also investigating whether or not the appetite-regulating mechanism could help with alcohol and drug addiction.

He hopes to publish early results next year, and said: ‘There is reason for optimism, particularly given the reports. Now it’s our job to do the research to validate those findings with clinical data.’

Meanwhile, a trial at the University of Oxford is testing semaglutide on patients at risk of dementia due to high levels in their brains of a certain protein associated with dementia. Researchers are investigating if the drug can reduce the amount of the protein, as well as calm down inflammation, another marker associated with a high risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Dailymail.co.uk