For Katherine Isaac, having a stroke in her 40s was shocking and frightening enough — but she also wasn’t prepared for the emotional toll while she recovered.

The Ajax, Ont., resident caught COVID-19 in 2021 and realized something was wrong when she couldn’t make it up the stairs at home without being out of breath. She called 911, and wound up hospitalized with low levels of oxygen. She was then placed on a ventilator in the ICU.

A few days into her hospital stay, Isaac realized her left arm was becoming harder to control. She couldn’t lift it, or even grip a fork.

“After about a week, they determined that I had a stroke,” she recalled.

After three months of outpatient therapy, the cybersecurity executive struggled to get back to day-to-day activities; even little tasks became a struggle — like holding a cellphone or reaching products at the grocery store.

“Emotionally, I wasn’t prepared for this lack of ability,” she said. “I had a couple of very, very public breakdowns.”

A new report suggests she’s not alone. Nearly a million Canadians are living with the aftereffects of having a stroke, including serious mental health issues, the report notes, with women often faring worse than men.

The paper, out today from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada — a charity dedicated to heart disease and stroke advocacy and research — also outlines how women in particular may not be getting the necessary support to manage anxiety or depression after recovering.

Mental health impacts ‘no less devastating’

A stroke can happen when blood stops flowing to any part of the brain, damaging or killing brain cells, which can cause lasting brain damage, long-term disability or death.

While the physical effects are well known, scientists say the emotional impact is less discussed, often leaving patients unprepared once they overcome the initial attack.

Research from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) in Toronto shows women have higher rates of mood and anxiety disorders than men, which puts them at greater risk of developing depression after stroke, the new paper noted.

“Although these are less visible than physical effects, they are no less devastating,” the team wrote. “And unfortunately women are hit the hardest.”

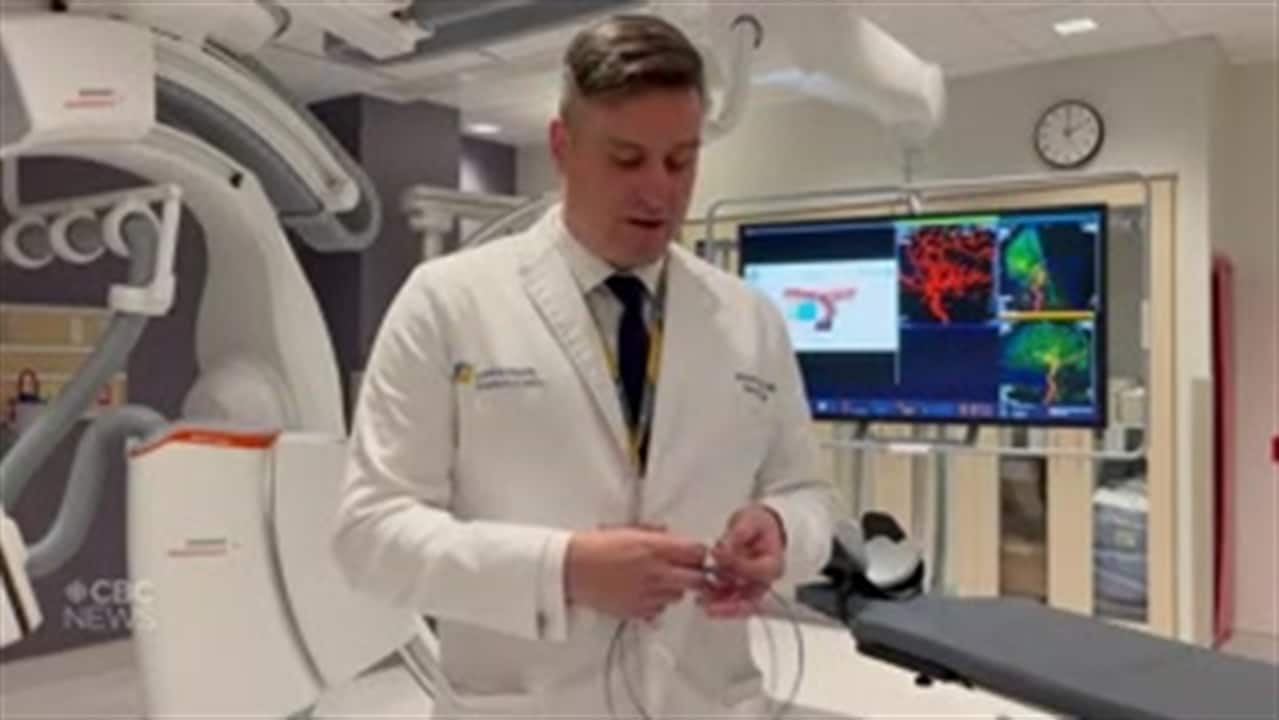

Dr. Michael Mayich at the London Health Sciences Centre’s University Hospital explains how a new medical device from Vena Medical is used to remove clots in the brain that cause a stroke and reverse those symptoms.

Women are also less likely to regain independence and report worse quality of life, the paper continued.

“We know from studies that have been done in many places around the world that women tend to get more anxious and depressed after a stroke — between 20 and 70 per cent more than males,” said Dr. Abraham Snaiderman, director of neuro-rehabilitation at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, who spoke to CBC News on behalf of the Heart and Stroke Foundation.

It’s a “complicated” issue to unpack, he added. Many women may be busier supporting their families and raising children, making them less able to get followup care, Snaiderman noted.

Women, in general, are also often more at risk for strokes in the first place, including in their older years, post-menopause, and during pregnancy, where their risk is three times higher than among people who are not pregnant, according to the Heart and Stroke Foundation.

More multidisciplinary care needed

Montreal-based cardiologist Dr. Christopher Labos, who wasn’t involved in the paper, said more needs to be done to support both women and men following a stroke diagnosis, to ensure people get adequate followup care — not just for their physical recovery, but also their mental health.

The ideal shift, he said, would be toward more multidisciplinary teams working in tandem.

“We treat all the other stuff — we treat the blood pressure, the cholesterol, the diabetes, when someone has a stroke or a heart attack. We should also be looking at treating depression when it’s appropriate to do so,” he said. “We need a team approach.”

Speaking of her time being hospitalized, Isaac said no one on her medical team prepped her for how to handle the aftermath of her medical crisis. She said having social workers available to patients could make a major difference in preparing them for a return to daily life, and the potential impact on their mental health.

Isaac did eventually connect with support in the community, including physiotherapy, and said she eventually began to regain her independence.

“For some reason, stroke isn’t seen as traumatic,” she added. “It was traumatic for me. And I consider myself lucky to have recovered as well as I have.”