More than three years after the start of the pandemic, many Covid survivors continue to struggle. Some, especially those who became so severely ill that they were hospitalized and unable to breathe on their own, face lasting lung damage.

To better understand the long-term impact of Covid’s assault on the lungs, The New York Times spoke with three patients who were hospitalized during the pandemic’s early waves, interviewed doctors who treated them and reviewed C.T. scans of their lungs over time.

One patient spent time connected to a ventilator; the other two were so debilitated they required months on a heart-lung bypass machine called ECMO. These patients were not yet vaccinated — for two, vaccines weren’t available, and the third had planned to get vaccinated but was infected before he could.

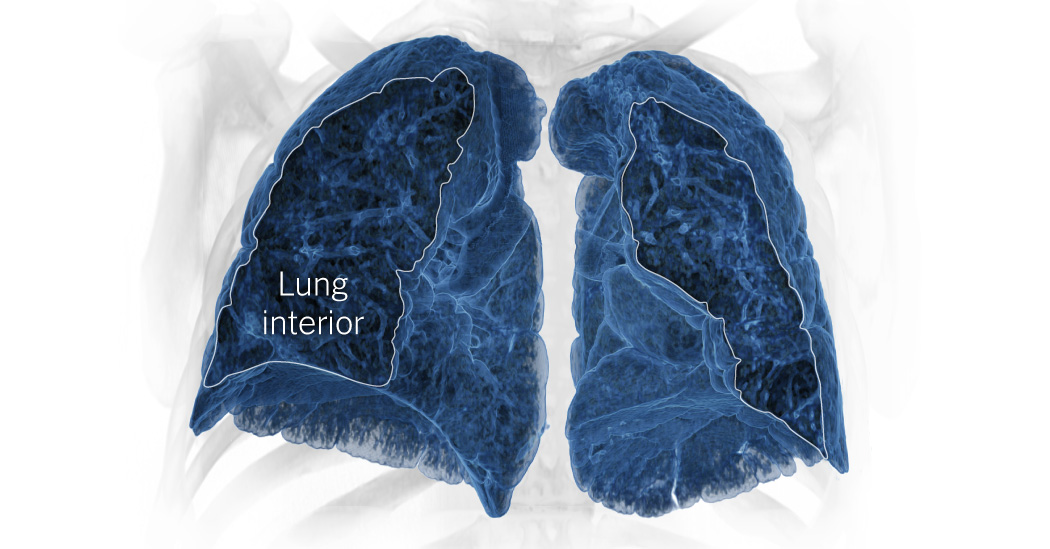

The Times analyzed hundreds of millions of data points from the patients’ scans to reconstruct their lungs in 3-D. The resulting visualization offers a vivid, visceral picture of damage that can linger years after infection and irrevocably alter everyday life.

Two and a half years after her infection, Ms. Rodríguez can accomplish most daily activities, but she becomes breathless and wheezes when she carries her toddler daughter or does chores such as mopping the floor. She uses an albuterol inhaler for exertive tasks like climbing stairs.

“She doesn’t have a lot of lung to give,” Dr. Sayah said. “She’s certainly at risk for ending up in more trouble if she does have additional respiratory issues in the future.”

Explore the graphic below using your device’s motion.

Tap to enable

A 3-D visualization comparing a healthy set of lungs with Ms. Rodríguez’s lungs 14 months after her infection. While the healthy lungs are filled with orderly airways that look like tree branches, Ms. Rodríguez’s are scarred and disorganized.

Healthy airways look like tree branches.

Ms. Rodríguez’s lungs are erratically scarred.

Tilt your device to rotate lungs

Healthy lungs are filled with millions of tiny air sacs called alveoli. Covid patients can develop scar tissue and permanent changes to the alveolar walls that limit airflow even after the inflammation and fluid of an active infection has cleared.

An illustration comparing different types of lung tissue. Healthy lung tissue has many open pockets where air can easily flow in and out. Lung tissue during an infection has areas filled with fluid and inflammation that inhibits airflow. Lung tissue with chronic damage shows scarred, thickened areas and collapsed sections with reduced airflow.

Many patients who experienced such severe lung damage early in the pandemic did not recover. Many died from a combination of direct injury by the virus and storms of inflammation incited by the immune system’s attempts to battle the infection. These three patients have been able to regain lung function to varying degrees, but the differences in their experiences reflect how unpredictable Covid’s impact can be.

Effects vary by how healthy people were before infection and how their immune systems responded to the virus. Ms. Rodríguez has come closer to recovering, most likely helped by her youth and previous good health.

Marlene Rodríguez, who has three young children, is wearing a temporary monitor to check her heart rhythm. She has made significant progress toward recovery, but said, “I don’t feel the same as how I used to.”

Meridith Kohut for The New York Times

Mr. Kennedy was overweight, had diabetes and had suffered a heart attack six weeks before his infection, factors that increased his risk for a serious outcome.

“Had I taken better care of my health before Covid,” he said, “Covid would probably have not done to me what it did.”

Mr. Muñoz was very healthy and had intended to get vaccinated, but had not managed to do so before becoming infected in the summer of 2021. Dr. Huang said that because his immune system was not primed by a vaccine to recognize the invading virus, it most likely reacted overzealously, causing an inflammation surge that made his illness worse.

All three patients were listed as candidates for lung transplants, an option doctors hope to avoid because patients require immunosuppressive drugs and often die within five to 10 years after transplant. Now, doctors say Mr. Kennedy and Ms. Rodríguez probably won’t need transplants, but Mr. Muñoz may need one eventually.

Andy Muñoz has been unable to return to work as a welding inspector and requires round-the-clock oxygen.

Meridith Kohut for The New York Times

In some ways, these patients have made better progress than doctors would have predicted. “We’re seeing examples where people do improve, even though they started out with a terrible-looking C.T.,” Dr. Huang said. But they’re unlikely to recover fully. “I don’t think anybody gets off completely scot-free if they’re that sick with Covid,” he said.

In addition to lung scans, doctors use several measures to evaluate respiratory function. A six-minute walk test evaluates patients’ cardiovascular health and fitness, tracking the distance patients walk and the way their lungs and heart respond. In March 2022, Mr. Muñoz walked 656 feet, slightly more than one-tenth of a mile, in six minutes. A year later, he walked over 1,443 feet.

Mr. Kennedy’s six-minute walk distance had increased to 2,024 feet in April 2023, from 1,489 feet in May 2021. But his oxygen levels still dipped after walking for several minutes in the April test.

A chart showing Mr. Kennedy’s blood oxygen saturation as he walks for six minutes. Although his oxygen levels begin above 95 percent, they quickly drop below 90 percent.

100% blood oxygen

saturation

100% blood oxygen

saturation

Another measure is called forced vital capacity, which is the volume of air a person can exhale after taking a deep breath. While all three patients have gradually improved on this measure, none have returned to the normal range of 80 percent of total lung capacity.

Mr. Muñoz’s forced vital capacity has increased to about 40 percent from 29 percent. Mr. Kennedy’s has increased to 59 percent from about 38 percent. Ms. Rodríguez’s has increased to 55 percent from 39 percent.

These numbers, and even the most detailed lung scans, tell only part of the story of infection and recovery. Mr. Muñoz’s girlfriend, Melissa Raymundo, said that early on, medical staff indicated that his chances of survival were low and discussed with her the possibility of letting him die. “Nobody thought he was going to make it,” she said.

“Breathing is still pretty hard,” Mr. Muñoz said. “But I’m home, I’m with my boys.”

Meridith Kohut for The New York Times

Mr. Muñoz missed months with his two young sons. He remembers saying good night to them in a call from the hospital just before being connected to ECMO. “I woke up three months later,” he said.

During those months, doctors kept him heavily sedated so he wouldn’t move and disrupt the lifesaving machine. It took months longer to wean him from the sedatives and for his lungs to become strong enough to breathe on their own.

Nearly two years after his infection, he cannot work and needs round-the-clock oxygen at home. He has developed pulmonary hypertension, a serious condition of high blood pressure in blood vessels leading from the heart to the lungs.

“Breathing is still pretty hard,” he said. “But I’m home, I’m with my boys.”

“Most important, you’re alive,” Ms. Raymundo said.

Tom Kennedy is tethered to a bulky oxygen machine with tubing that he calls “this leash that tugs at my nose.”

Meridith Kohut for The New York Times

Mr. Kennedy choked back tears as he recounted being in the hospital.

“I remember telling my wife to tell my children that I loved them,” he said. And he recalled being on the ventilator while his wife, Gayle, read aloud from one of his favorite books, “The Screwtape Letters.” While hospitalized, he experienced delirium, hallucinating that he had been kidnapped.

Mr. Kennedy prayed with his wife, Gayle, before dinner in their Houston home.

Meridith Kohut for The New York Times

He has gradually returned to his job as general counsel of USA DeBusk, which provides services for oil and chemical companies. He works from home because he is continually tethered to a bulky oxygen machine with tubing that he calls “this leash that tugs at my nose.”

He said, “I don’t like it one bit, but it’s a lot better than where I thought I was headed.” Over time, the amount of oxygen he needs has diminished and, with a portable tank, he can play golf.

“I get tired, I feel bad a lot, but that’s just my new normal,” Mr. Kennedy said. He feels grateful.

“Whatever is the final stage before you die, that’s where I was,” he said. “But now I’m just in the group that deals with people that have really bad lungs.”

Ms. Rodríguez no longer needs supplemental oxygen, but she still becomes winded lifting heavy items or doing taxing activities like climbing stairs.

Meridith Kohut for The New York Times

Ms. Rodríguez didn’t meet her newborn daughter, Vianney, until she was removed from the ECMO machine, two and a half months after the baby was born.

She briefly returned to work as a receptionist at a plant nursery, but after getting laid off and trying another job, she and her husband, José, who has a chronic medical condition, decided, for health and financial reasons, to move in with his parents. Now she spends her days caring for her three young children.

“I don’t feel the same as how I used to,” she said. She becomes winded when lifting heavy items or doing vigorous activities. She has experienced back pain and takes anxiety medication.

Still, it’s “one of the most remarkable recoveries,” Dr. Sayah said. “I don’t mean to imply that she’s recovered normal lung function, but when the expectation was that this person would for sure die without a lung transplant, to go from death to living at home without supplemental oxygen is a huge sort of success.”

Today, with coronavirus vaccines, antiviral treatments and other developments, doctors say they encounter few patients who are so severely afflicted. But they worry about those who wrestle with Covid’s enduring effects.

“People think that it’s kind of a one-and-done thing, like you can get over it like a common cold,” Dr. Huang said. “We’re left with a population of people like this that are kind of in this limbo state.”

Sources

The 3-D lung visualizations were created from reconstructed computerized tomography (C.T.) scans that calculated tissue density. C.T. scans use X-rays to calculate the differences between blood, bones, internal organs and other soft tissue.

Each scan produced hundreds of slices of the lungs, at different angles, that The New York Times combined into volumetric models for rendering in 3-D software. Reconstructing the slices produced more than 700 million 3-D cells, called voxels, that were evaluated and programmatically filtered, based on density, to isolate the bones and lungs.

The Times reviewed the C.T. scans, the underlying data and the resulting 3-D visualizations with pulmonologists and with radiology and visualization experts:

-

Dr. Howard Huang, lung transplantation section chief at Houston Methodist J.C. Walter Jr. Transplant Center -

Dr. John W. Nance, Jr., associate professor of clinical radiology at the Houston Methodist Academic Institute -

Dr. David Sayah, clinical chief of the division of pulmonary & critical care medicine at U.C.L.A. Health -

Dr. Ayodeji Adegunsoye, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago -

Dr. Kristin Schwab, pulmonologist at U.C.L.A. Health -

Dr. William Moore, clinical director of radiology information technology at N.Y.U. Langone Health -

Dr. Elliot Fishman, director of diagnostic imaging and body computed tomography in the department of radiology and radiological science at Johns Hopkins Medicine -

Sebastian Krüger, conceptual engineer at Siemens -

Alexander Brost, head of clinical innovation and concepts at Siemens

The healthy lung scan shown for comparison was of a 54-year-old midwestern woman and was performed at the Houston Methodist Outpatient Center.