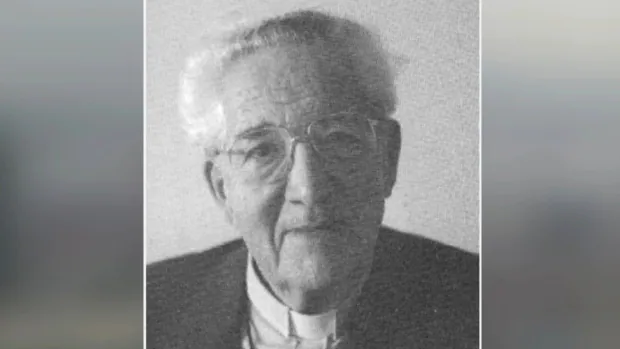

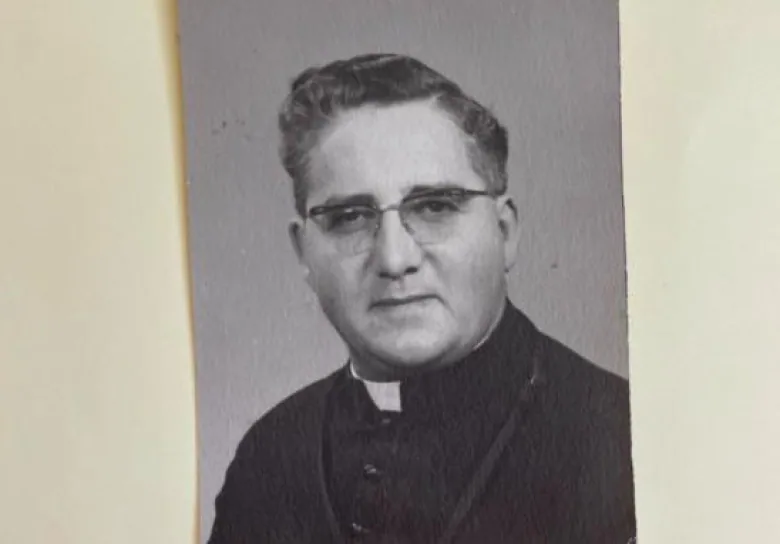

A British Columbia woman claims she was told the late Father Georges Chevrier had no history of the kind of sexual abuse complaints she was bringing forward.

Then she listened to an acclaimed podcast titled Stolen: Surviving St. Michael’s.

Now she’s suing.

The woman — known as LV — filed a B.C. Supreme Court claim this week against Chevrier’s estate and the corporation of the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Vancouver, which she accuses of failing to tell her the dead priest had a “known history of allegations of sexual abuse” when she first asked for compensation.

LV claims she only learned about Chevrier’s past through Stolen, a podcast hosted by investigative journalist Connie Walker, which unearthed numerous allegations of sexual and physical abuse against staff at St. Michael’s residential school in Saskatchewan, where Chevrier served as principal from 1950 to 1953.

According to the podcast, 10 people claimed he sexually abused them during that time.

“It is absolutely telling people that they are not alone. And people have been alone with their stories for feeling that they were the only one for a long time,” said Leona Huggins, who supports clients for Kazlaw, the legal firm handling LV’s case.

Huggins says LV had already been thinking of suing when she heard the podcast.

“That was the impetus that kind of said, ‘Wow — okay.'”

Taking aim at ‘the culture’

LV claims Chevrier groomed and sexually abused her between 1973 and 1977 when she was a child and he was a priest at Our Lady of Fatima Parish in Coquitlam, B.C., about 32 kilometres east of Vancouver.

According to the claim, Chevrier exploited her “pre-existing vulnerabilities arising from trouble at home” to earn her trust and abuse her on church premises.

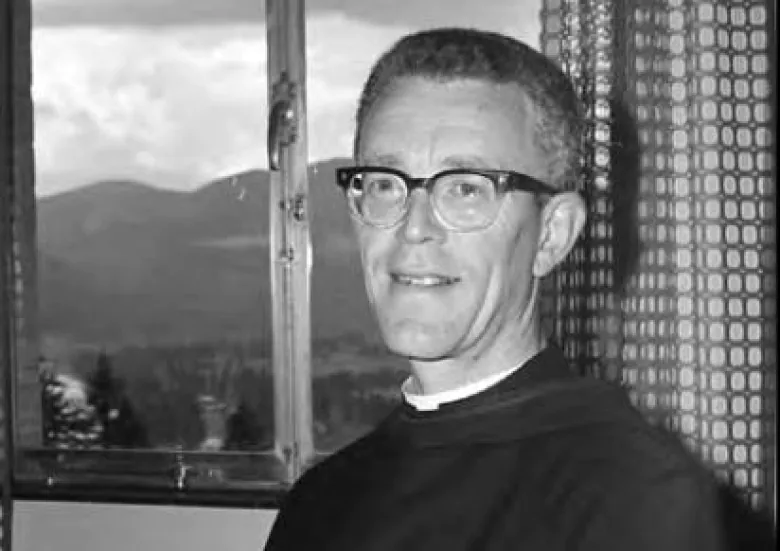

The claim is one of two B.C. Supreme Court lawsuits filed in recent weeks against the estates of dead priests. The other claim accuses the late Father Harold Daniel McIntee of sexual abuse at Sacred Heart Catholic Church during the years McIntee was based out of Terrace, a city in northwest B.C.

McIntee later served time for 17 counts of sexual assault against males, including victims he abused while he was at St. Joseph’s residential school in Williams Lake, in the province’s central Interior.

Both the claims against Chevrier and McIntee were filed by Kazlaw’s Sandra Kovacs, who has brought forward a series of lawsuits in recent years from clients seeking justice in relation to historic abuse involving the Catholic Church.

For years, Huggins has volunteered with the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests. She recently began working with Kovacs to support her clients while they navigate the legal process.

The lawsuits take aim at both alleged individual abusers and the range of defendants — including dioceses and religious orders — accused of collectively enabling a “pattern and continuum of systemic abuse suffered by children and vulnerable persons” in Catholic institutions worldwide.

“The culture permitted dark pedophile networks to form,” LV’s claim reads.

“The culture silenced witnesses, complainants and whistle-blowers enabling perpetrators to continue to commit their grievous crimes without any or any reasonable sanction.”

The church has yet to file a response.

The allegations have not been proven in court.

‘Nothing has changed’

Kovacs recently settled a case brought by former high school seminarian Mark O’Neill against the estate of Father Harold Sander, a Benedictine monk accused of sexually assaulting O’Neill at Seminary of Christ the King in Mission, B.C., about 76 kilometres east of Vancouver.

O’Neill was one of three complainants who testified at a criminal trial that resulted in Sander’s acquittal on sexual assault charges in 1997. All three have since brought civil cases against the dead monk and the church, two of which are still working their way toward trial.

Kovacs says the civil process can take aim at the roots of abuse in a way that the criminal justice system cannot.

“How did this happen? Who enabled it? Who covered it up? Who permitted it to continue? Who allowed it to continue in different areas?” Kovacs said.

“Nothing has changed in the underlying foundational concerns about why abuse happens in the church.”

The power of podcasting

While at the CBC, Connie Walker — who is from Okanese First Nation, east of Regina, Sask. — created the award-winning podcast Missing and Murdered: Finding Cleo. She made Stolen: Surviving St. Michael’s for Gimlet and Spotify. The show has been met with universal praise: Esquire magazine recently named it one of the best podcasts of 2022.

The show is rooted in Walker’s family history, beginning with her father’s encounter with a residential school priest one night in the late 1970s while he worked as an RCMP officer. Walker says her team of journalists spent 10 months investigating the horrors of St. Michael’s.

“What we uncovered was really shocking. We found allegations against 17 Oblate priests … 15 staff members and 13 nuns, and against those 45 adults, we found 219 allegations,” she said.

Walker says many of the allegations against Chevrier involved very young children who he would try to bribe with candy.

She says the Catholic church and the Oblates have never published lists of those who have been credibly accused of sexual abuse, leaving alleged victims like LV wondering if they are alone, scattered in communities across North America where abusers were sent without any kind of warning about their past behaviour.

“It’s not surprising to me that there are people out there looking for the information — exactly the information that we uncovered — in our investigation,” Walker said.

“I think the power of podcasting, the power of investigative journalism is huge, in terms of helping people not just understand the truth of what happened in residential schools, and the truth about the crimes committed against children, but also helping people who are seeking justice and accountability.”

Both LV and the claimant suing McIntee are seeking damages for the harm they allegedly suffered at the hands of both priests. Both are also seeking a declaration that the alleged culture of secrecy “constitutes a public nuisance.”

“None of my clients have said that restitution is their number-one goal,” Kovacs said.

“That cheque at the end of the process is not what they’re here for. It’s an important piece, but usually what they’re looking for is truth. They want answers. They want accountability. They want validation.”