A Canadian journalist is defending his decision to travel the U.S. in blackface and write a book about racism, after facing a storm of criticism online.

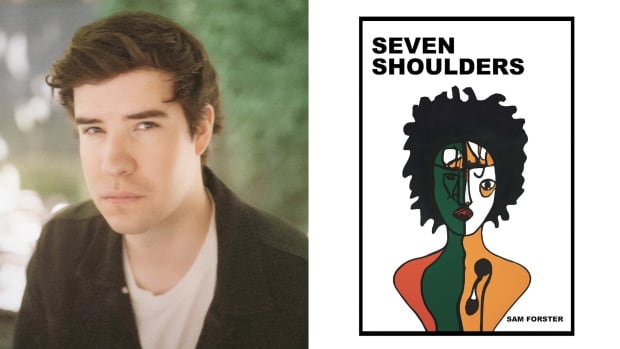

“Last summer, I disguised myself as a Black man and traveled throughout the United States to document how racism persists in American society,” Sam Forster, who is white, posted Tuesday on X, formerly Twitter. “Writing Seven Shoulders was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done as a journalist.”

The reaction was swift and brutal, with X users expressing anger, amusement and confusion, and telling Forster he should have simply spoken to Black people to understand their experiences.

“It’s hard to simultaneously draw the ire of black people, white people, conservatives, AND liberals… But I think you’ve just done it,” rapper and podcaster Zuby replied on X.

Several Black scholars who study race relations and write about the Black experience told CBC News that Forster’s use of blackface is dehumanizing and troublesome, regardless of the context. Forster himself defended the book and the methods he used to write it in an interview with CBC News.

If you knew any black people, they would have saved you from getting torched on the internet because they’d have told you this was a bad idea

—@BlackKnight10k

‘Why do we need a white person to do that?’

George Dei, director of the Centre for Integrated Anti-Racism Studies and a social justice professor at the University of Toronto, told CBC that Seven Shoulders feeds into questions around who has the authority to speak about the Black experience.

“There are Black scholars who write on these issues, and they have said all that needs to be said. So why do we need a white person to do that?” he said.

“We also need to question why we live in a society where people have to pretend who they are not in order to understand something.”

Forster grew up in Edmonton and attended both the University of Alberta and the University of Toronto. He now lives in Montreal, and has written for various publications including The National Post.

He describes the self-published book as an homage to John Howard Griffin’s 1961 book Black Like Me, and others who did “journalistic blackface” in the 1940s and 50s.

In Black Like Me, Griffin recounts the six weeks he spent travelling through the southern U.S. after darkening his skin to better understand what life was like for Black Americans under segregation.

In Seven Shoulders, Forster writes that his book offers a unique perspective on race in the modern era, because “for a short window, I became Black. I experienced the world as a Black man.”

He goes on to write, “Nobody has an experiential barometer with respect to race, for that matter … nobody except for me,” concluding, “My barometer is better than anyone else’s.”

Speaking with CBC News in a phone interview Thursday, Forster said he understands there’s a distinction between a project like his and living one’s entire life as a Black person — but he stands by his statement in the book summary on Amazon, where he calls Seven Shoulders “the most important book on American race relations that has ever been written.”

“If I thought this would be the second best book, I wouldn’t put it out,” he said.

The book includes transcripts from two interviews with unnamed Black politicians — Forster says he didn’t want to stigmatize them by attaching their names to the book — and says they were not aware of his blackface project.

Author wore contacts, makeup, afro wig

In the book, he describes his disguise as consisting of coloured contact lenses, makeup and an afro wig. He said no one recognized his disguise during his reporting.

Forster would not send a photo of himself in blackface, saying he wants the book to be taken seriously and not become a “minstrel show,” in reference to the historical use of blackface by white comedic performers to disparage Black people.

“I went about it in a way that was thoughtful and creative, and I think the insights that can be gleaned from the book are tremendously valuable,” he told CBC News.

Paul Lawrie, an associate professor at York University and Afro-America historian, says his initial reaction to Forster’s announcement that he’d written a book about travelling in blackface was not one of outrage, but “bafflement.”

He says the use of blackface is still troublesome, regardless of context.

“I think at the heart of it is the dehumanization of Black folks, because it’s being able to say, ‘We can inhabit your body, at will, to whatever effect we wish,’ ” he said. “And just because it’s not a comic effect doesn’t mean it’s any less dehumanizing.”

In the book, Forster poses as a hitchhiker in various U.S. cities, first as a white man and then later in blackface, which he says he wore for about three weeks last September. He writes that he is ultimately offered seven rides as a white man, and only one while in blackface.

He concludes that this is an example of subtle discriminatory behaviour, or what he calls “shoulder racism,” named for the shoulders of the highways where he thumbed rides, but he dismisses broader notions of systemic racism.

Institutional racism (the anti-Black variety) is effectively dead,” Forster concludes in the book. “Most of what’s left of racism in this country are the few, socially narrow opportunities for soft interpersonal racism: shoulder racism.”

A ‘comically ahistorical’ understanding of racism

Lawrie says Forster’s conclusion reflects a misunderstanding of the connections between individual attitudes and broader societal issues, noting the actions of the dismissive motorists “don’t exist in a vacuum.”

As for Forster’s claim that he’s written the most important book on race relations in America, Lawrie says that shows a “comically ahistorical” understanding of the issue.

“To just disregard centuries of writing and thinking by scholars and individuals of all racial backgrounds on this issue is … wow,” he said.

In Lawrie’s view, Forster’s approach ultimately perpetuates the notion of Blackness as a “problem” to be solved.

In the era when Griffin wrote Black Like Me, this was commonly called the “Negro problem,” before the language shifted to the “race problem” in the 1960s. Lawrie says it’s an idea that still exists today in various iterations.

“If you just continue to see a group of people or peoples as problems and objects of inquiry and things to be investigated, poked and prodded and questioned, where does that leave — not just their humanity — but where does that leave our actual understanding of various forms of Black lives?” he said.