Peter C. Newman, who for more than a half-century unearthed revelations while chronicling power brokers on Parliament Hill and in Canadian boardrooms — earning praise for his writing style and occasionally the wrath of his subjects — has died. He was 94.

Alvy Newman, his wife, told The Canadian Press that the celebrated author died on Thursday morning in Belleville, Ont.

When Newman published his first book, The Flame of Power: The Story of Canada’s Greatest Businessmen, at 29, the jacket described the newcomer as “intrigued with the power wielded by that small golden group whose acquisitive itch has catapulted them beyond the prosaic strivings of ordinary men.” It was a description written by Newman himself, he revealed in the 2005 memoir Here Be Dragons: Telling Tales of People, Passion and Power.

Decades later, Newman told CBC’s The Hour more pithily that he wanted to be remembered as a “shit disturber.”

“I’m neutral, I attack everybody,” he said. “I think they need to be attacked, they’re responsible to us.”

In more than two dozen books and hundreds of columns in major Canadian publications, Newman put prime ministers under the spotlight as well as business titans including Conrad Black, Leonard Asper, the Bronfman family and the men over the course of centuries who led the Hudson’s Bay Company.

After his first reporting job at the Financial Post and a two-year stint as the Toronto Star’s editor in chief, Newman served as editor of Maclean’s from 1971 to 1982, where it gained influence at the height of the magazine boom as he oversaw its transition to a weekly publication.

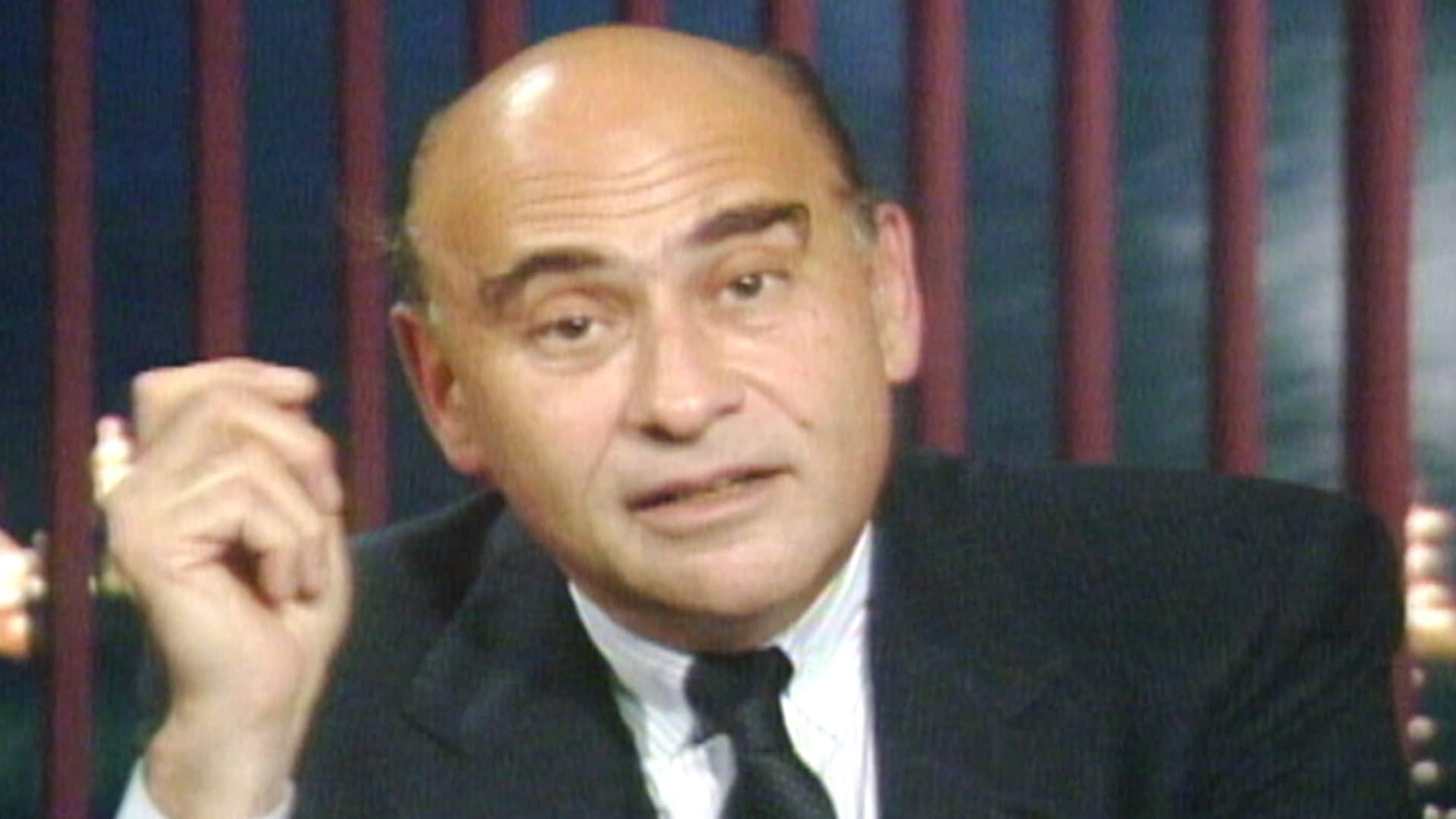

Iconic Canadian author and journalist Peter C. Newman talks about the Liberal party and causing trouble for politicians.

Entering journalism, he was inspired by writers such as Ralph Ellison, Anthony Sampson and Norman Mailer, becoming a Canadian practitioner of what was described as “the New Journalism,” a form of narrative non-fiction marked by a subjective style.

Newman reached his pre-eminence as a Canadian commentator after arriving in Halifax slightly more than two decades earlier as, he wrote in his memoir, a “Jewish refugee with faulty English.”

Newman was appointed to the Order of Canada in 1978 and promoted to the rank of companion in 1990, recognized as a “chronicler of our past and interpreter of our present.”

Mulroney tapes controversy

Beginning with 1963’s Renegade in Power: The Diefenbaker Years, Newman’s books and columns in major Canadian publications took on the most powerful office in the country, a trend that followed with books such as A Nation Divided: Canada and the Coming of Pierre Trudeau (1969) and The Secret Mulroney Tapes: Unguarded Confessions of a Prime Minister (2005).

Brian Mulroney considered the book a personal betrayal after a decades-long relationship, later describing in 2007’s Memoirs: 1939–1993 early sailing trips on the Rideau Canal with Newman, “whiling away the hours in funny, stimulating and gossipy political discussions.”

Based on 98 interviews conducted over 12 years, it was eagerly received by the Ottawa press gang, given it contained Mulroney’s unvarnished and sometimes harsh assessments of the man he defeated for the party leadership, Joe Clark; his successor Kim Campbell; as well as former ally Lucien Bouchard and Liberal prime minister Jean Chrétien.

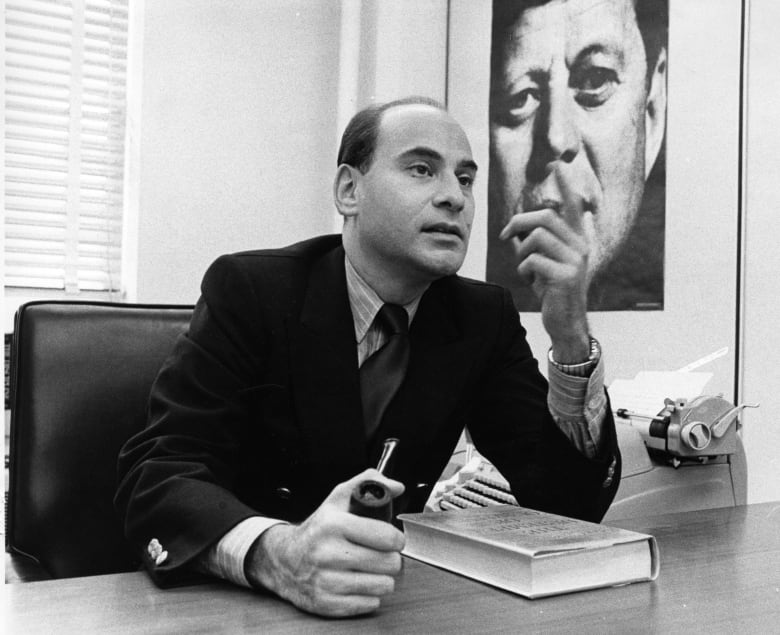

The Journal takes a look at Peter C. Newman’s new book The Company of Adventurers, a popular history of the Hudson Bay Company. (Original broadcast Oct. 28, 1985)

On Clyde Wells, the Newfoundland premier who helped doom the Meech Lake accord in 1990, Newman quotes Mulroney as saying, “nothing has ever compared to the lack of principle of this son of a bitch.”

Mulroney knew Newman recorded their conversations and didn’t challenge the book’s accuracy, but he disputed the ownership of the tapes and wanted to direct how any profits from them should be distributed. The former prime minister filed a lawsuit, although the matter was settled out of court before reaching trial.

Digital Archives8:35Was John Diefenbaker a good prime minister?

Biographer Peter C. Newman says no, callers say yes.

Newman downplayed their closeness — yes, Mulroney was in the wedding party of his third marriage in the mid-1970s, he said, but they hadn’t spoken since 2001.

It was far from the first time Newman was assailed by his subjects. Former prime minister John Diefenbaker, in notes found in his personal collection, described the author as a “literary scavenger of trash,” while Black threatened to sue after 1982’s The Establishment Man: Conrad Black, A Portrait of Power.

“Conrad Black, who I had some considerable part in inventing, became the poster boy for capitalism gone berserk,” Newman wrote years later.

Documented Liberal Party nadir

In what turned out to be his last major book on contemporary politics, Newman depicted Michael Ignatieff’s return to Canada and nomination as Liberal Party leader after years of acclaim as a political thought leader in British and American academic circles.

Instead of a tale of triumph, campaign blunders and a third-place showing in the 2011 election yielded that year’s, When the Gods Changed: The Death of Liberal Canada.

Newman predicted doom for the Liberal Party in an interview with CBC’s The House while promoting the book.

“They’ve lost their Toronto fortress, their Maritime fortress and Quebec fortress and they haven’t been out west in awhile,” he said.

The House13:54Peter C. Newman – Interview

Newman, on the same book tour, would describe himself to a Belleville, Ont., reporter as uninterested in taking on Stephen Harper and his Conservative government as a subject for a future book.

“He’s not interesting enough. There’s no human dimension,” said Newman.

Not just a confidante or foil of the powerful, Newman often took on the broader subject of what it means to be Canadian, including in the context of sharing a continent with the world’s superpower.

“This country remains fallow ground for heroism,” he wrote in the 2010 essay collection Heroes: Canadian Champions, Dark Horses, and Icons. “Risk-takers — and every hero must be one — cannot play to a public that ranks our pledge to preserve peace, order and good government above the Yanks’ pursuit of hedonism and happiness.”

‘Flight from fear’ to Canada

He was born Peta Neumann to Jewish parents on May 10, 1929, in Vienna. His mother, Wanda, had insisted on an Austrian hospital over the border from their native Czechoslovakia. His father, Oscar, owned a beet refinery, the main employer in his small Moravian town in Czechoslovakia, leading to a privileged upbringing in a manor with servants until the German occupation began in 1938.

They left their Breclav residence shortly before Nazi officers took it over, he wrote in his memoir, leading to a months-long “flight from fear” across Europe with his parents and aunt to get to Canada, after a fortuitous meeting with a Canadian Pacific Railway executive in Europe helped pave the way for a successful entrance visa — provided the family was baptised in the Catholic Church.

In Here Be Dragons, Newman wrote about the struggles of his parents assimilating to Canadian life, the death of his father in 1950 and his own, almost desperate search for identity.

“Nothing compares with being a refugee; you are robbed of context and you flail about, searching for self-definition. When I ultimately arrived in Canada, what I wanted was to gain a voice. To be heard,” he said.

He wrote sometimes scathingly about teachers and classmates at Toronto’s Upper Canada College. The University of Toronto and especially the Canadian Royal Navy came off better in his recollection.

He was a naval reservist for decades, reaching the rank of captain, leading to a double life “as a pushy journalist and an undercover naval officer, in love with both professions and determined not to betray the integrity of either. It was a tough gig.”

That conundrum, as well as his close access to the influential, led to some ethical challenges. Newman admitted he was, in effect, used in the late 1960s by Pierre Trudeau and Marc Lalonde, who he said supplied him with false information in order to help damage intraparty Liberal rivals.

When writing on the navy — at such times he would have his naval pay suspended, he later wrote — he admitted to “playing into the navy’s agenda of goading its political masters into spending more on its appropriations.”

Lamented his personal faults

Accustomed to turning his sharp eye outwards, in his memoir he lamented the personal faults that helped lead to three failed marriages and estrangement from the daughter born to his first wife.

Of his second wife, the fellow Maclean’s journalist Christina McCall, Newman wrote years later: “In the end, we divorced over religious differences: I thought I was God, and she didn’t. She haunts me still.”

Newman, often in a sailor’s cap for his public and television appearances, continued writing at a prolific pace even after undergoing a quadruple bypass in 1998, telling the Toronto Star in 2009 he sometimes spent up to 15 hours a day at his desk.

In 2012, he told then-CBC host George Stroumboulopoulos that in his writing he was “searching for the ring of truth,” as objective truth was “too big a concept.”