This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. The yield on the one-year Treasury bill has broken decisively above 4 per cent. We are tempted. Let us know if you are, too: [email protected] and [email protected].

Fangs, still sharp

The long-term case for owning the very big tech companies (Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, Apple and Google) is that you get a lot of upside and a just a little downside. In an expansion, the monster techs use cheap capital to scale like mad. In a contraction, the boatloads of cash these companies spit out, a reflection of their strong competitive positions, provide a safe haven.

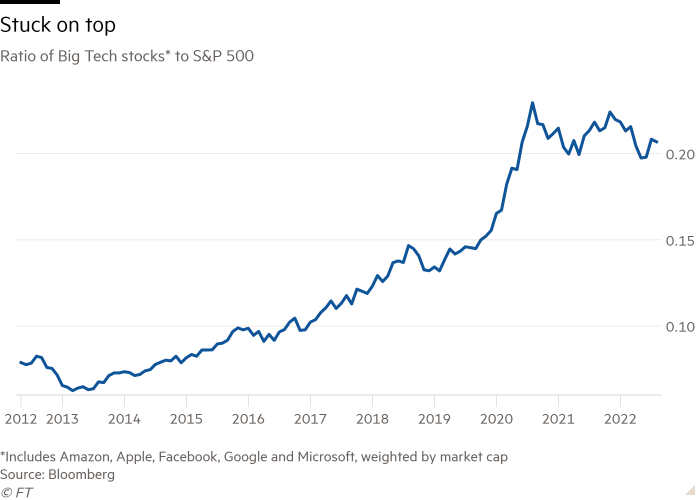

Can this happy story survive rising interest rates? The tech bull run began in a zero-rates world. Many pundits argue that higher rates make future cash flows less desirable and should be most painful for growth stocks. We’ve been sceptical about this argument, but lately the sceptics have looked prescient. As rate expectations rose, Big Tech fell 27 per cent from the peak to today, against 19 per cent for the S&P.

But note how trivial the recent weakness in Big Tech looks compared to its ascent. Zooming out:

Things look less neat once you start digging in. Distinctions between the companies are important. Apple, the ultimate quality stock, has beat the S&P this year while Facebook’s valuation was getting chopped in half. Former Fang Netflix is now valued more like media than tech.

But overall, the promise of big scale, competitive moats and high profits providing downside protection has panned out.

The next test is earnings. Higher rates alone probably aren’t enough of a catalyst to push down Big Tech much further from here. If this bear market works anything like the dotcom mess, the reigning five tech stocks won’t drop until profitability falls hard, Jason Pride, chief investment officer for private wealth at Glenmede, told us.

That is possible, but it is the same fear stalking the rest of the stock market. We still like big tech.

Opendoor revisited

Last November, Zillow’s home-flipping operation blew up. The company, which had been in the home-listing business before it entered the home-flipping business, thought it had special insight into the housing market. It did not.

When the increases in house prices flowed fast and smooth, the business rolled along OK. When that stopped, Zillow discovered that it was (in the chief executive’s words):

. . . unable to predict future pricing of homes to a level of accuracy that makes this a safe business to be in . . . We pump [current volatility levels] into [our] model and the model cranks out a business that has a high likelihood, at some point, of putting the whole company at risk, not just the [house flipping] business. But in the more normal case, it just causes a ton of volatility in earnings, which is not a great look for a public company.

This is the kind of finance story that makes journalists and casual observers feel wonderfully smug. Everyone knows that the house-flipping business is at best highly cyclical, and at worst a craven form of gambling. Everyone remembers the great financial crisis. Trying to industrialise this game, while posturing as a tech company, is the height of arrogance. The market gods were never going to tolerate it.

But this thumbnail morality tale is a poor fit with the case of Opendoor, which was in the flipping business years before Zillow, and operates at a larger scale. When Zillow’s wheels flew off, Opendoor’s stayed attached, and have stayed there for the three quarters it has reported since. Revenue has risen. Gross margins have softened only a little, on an annual basis. The sales/inventory ratio and return on assets look OK. In the past two quarters, the company reported an operating profit on a GAAP basis for the first time.

There are clouds on the horizon, as you might expect, given that the housing market has continued to sour. In the second quarter earnings call, early last month, Opendoor said a rougher market meant that in the current quarter, sales would slow abruptly and operating losses would resume.

The market has not been fussed about the details. News from the housing market has only gotten worse since the Zillow meltdown, and Opendoor’s shares have fallen steadily from $24 to under $4 over 10 months.

On Monday, Bloomberg reported that Opendoor:

lost money on 42 per cent of its transactions in August, according to research from YipitData. Opendoor’s performance — as measured by the prices at which it bought and sold properties — was even worse in key markets such as Los Angeles, where the company lost money on 55 per cent of sales, and Phoenix, where the share was 76 per cent.

As recently as May, according to YipitData, homes sold at a loss were around 5 per cent of the total.

Cue more smugness. Between Opendoor’s founding in 2014 and the middle of this year, US home prices have risen at a compound rate of 8 per cent annually, on National Association of Realtors data. A monkey could have made money buying houses, waiting a few months, then selling. Now the monkeys will get what is coming to them.

This is not quite fair. First, we don’t know yet whether the YipitData translate into a catastrophic loss for Opendoor, or something not much worse that the quarter the company forecast back in August. Second, we don’t know how much Opendoor’s business model really depends on home price appreciation. The company makes the case that margin also comes from three other sources. One, by offering sellers certainty of transaction, it sells something like home sale insurance, which translates to better purchase prices. Two, it offers ancillary services (title, escrow, closing and so on). Three, its scale allows it to dress up a house for sale, and get it sold, very efficiently, while spreading risk across a big portfolio.

Are these sources of profit enough to allow Opendoor to earn back its cost of capital across a full housing cycle? It might. We don’t know yet, and the company doesn’t know either. Sure, in a bear market for housing, the company will report losses. But that’s not the question. The question is whether it makes it through to the next bull market, holding enough capital to grow again.

What we do know is that the business will stay very volatile — a bad look for a public company, in the words of Zillow’s boss. Market makers of all sorts, even really good ones, trade dirt cheap. Goldman Sachs trades at about one times its book value. So, after its decline, does Opendoor. This looks about fair. Opendoor faces existential risks that Goldman does not, but should it survive this downturn, its growth potential is much higher.

One good read

The bear case on earnings estimates.

Recommended newsletters for you

Cryptofinance — Scott Chipolina filters out the noise of the global cryptocurrency industry. Sign up here

Swamp Notes — Expert insight on the intersection of money and power in US politics. Sign up here