So tight is the supply of dollars in Nigeria these days that even big international airlines are struggling to repatriate revenue from ticket sales. Emirates announced it would suspend flights to and from Nigeria from September, only resuming flights to Lagos when the central bank released $265mn of the estimated $464mn that airlines say it was sitting on.

Currency traders and investors say Nigeria’s chronic dollar shortage, a constant complaint of businesses operating in the country, has recently tipped into crisis. The naira, which trades officially at N421 to the dollar, has fallen to N700 on the parallel market, with talk that it could weaken further.

“It’s really a perfect storm,” said Iyin Aboyeji, a fintech entrepreneur in Lagos. “No one could have foreseen it: low oil production and high dollar demand.”

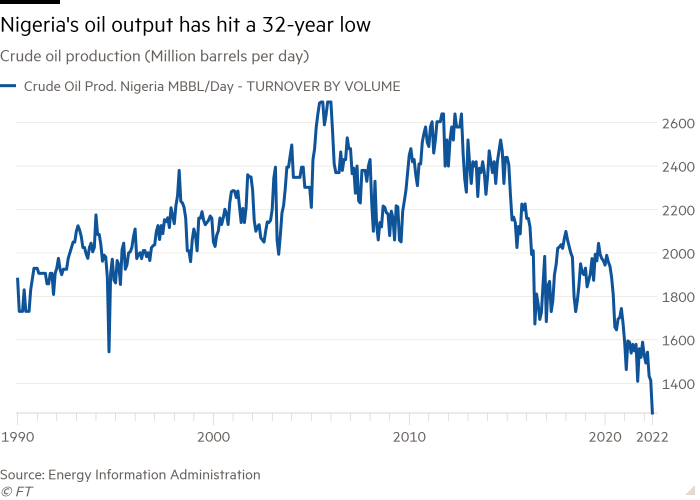

On the supply side, dollar revenues from oil have plummeted because of massive theft, pushing down official daily production of crude to 1.1mn barrels, far below Nigeria’s Opec quota of 1.8mn b/d. Angola has now usurped Nigeria as Africa’s biggest oil producer.

Nigeria’s petrol subsidy, under which its car owners enjoy among the cheapest fuel in the world ($0.40/litre), means the federal government receives less revenue. The higher the oil price, the bigger the gap between the real and the subsidised price and the higher the bill for the government. Nigeria will spend an estimated $9.6bn on petroleum subsidies this year, about 2 per cent of gross domestic product and almost 10 times the budgeted amount.

On the demand side, August is always a crunch month because an estimated 100,000 Nigerians need dollars for tuition fees abroad.

Political parties also scrambled for dollars to hand out to delegates in presidential primaries held in May and June, pushing demand and supply further out of kilter. Central bank governor Godwin Emefiele may have compounded the problem by warning politicians that those caught changing naira into dollars on the black market would be arrested.

Wilson Erumebor, economist at the Nigerian Economic Summit Group, a think-tank, said of the widening spread on the black market, “If we had enough supply of foreign currency, this would never be an issue.”

The collapsing naira makes imports more expensive, stoking inflation, which reached a 17-year high of 19.6 per cent in July. The central bank has raised interest rates by 250 basis points to 14 per cent since May.

Nigeria has a complex and opaque exchange rate regime with multiple exchange rate “windows”. The central bank seeks to manage limited supply and to prioritise allocation of dollars to areas of the economy, such as agriculture, that it deems a priority. Last year, the bank stopped selling dollars to bureau de change operators to guard its limited reserves of $38bn, further spooking the market.

“The black market is the free market,” said Aboyeji, who added that Nigerians needing dollars for things such as school fees should use the parallel market instead of receiving what is effectively subsidised dollars at the official rate.

Investors complain that the multi-window system is unnecessarily opaque. Those who receive dollars can buy naira on the black market in a gambit known as “round tripping”.

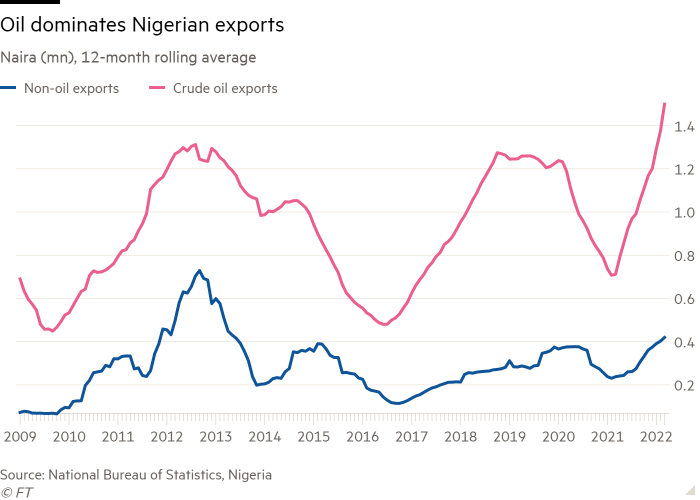

Nigeria’s dollar crisis has its origins in the oil price crash of 2014, when prices fell by 52 per cent in six months. The federal government, which collects taxes worth only 6 per cent of GDP, one of the lowest rates in the world, earns the bulk of its revenue and almost 90 per cent of its foreign exchange from oil exports.

Erumebor of the NESG said Nigeria’s problems were compounded by a lack of significant exports in sectors other than oil. Data from the national statistics agency put Nigeria’s non-oil export earnings in 2021 at $16bn against $145bn from crude oil sales.

Years of under-investment in oil infrastructure have eroded production, meaning Nigeria has not benefited from the higher oil prices resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Widespread crude oil theft, estimated by the Nigerian National Petroleum Company at 400,000 barrels daily, has depressed production. Some pipelines have suspended operations, including a Shell installation that shut down in June. Nigerian authorities have contracted Government Ekpemupolo, a former militant in the Niger Delta, to secure pipelines.

Nigeria’s other sources of foreign exchange earnings have also dipped. Foreign direct investment in 2021 was just below $700mn, down from $3.1bn at the start of president Muhammadu Buhari’s tenure in 2015.

Mosope Arubayi, economist at IC Group, an investment consultancy, said Nigeria had become less attractive for foreign investors, partly thanks to the difficulty of repatriating revenue.

“The FX market is very tight in terms of liquidity,” she said. “Nigeria relies significantly on oil inflows, but you need other flows of capital like remittances, most of which do not go through official channels.”

Half a dozen analysts and executives interviewed by the Financial Times, who declined to be named for fear of central bank retribution, said the bank’s policies were damaging the investment environment.

“They give you no indication of when you’ll be able to get your money out of the country,” said one executive, adding that their company would make no further investments until the matter was resolved. “Investors walk away.”

Experts said there would be no significant change of strategy before presidential elections to be held next February.

But Charlie Robertson of Renaissance Capital said the central bank may only be delaying the inevitable. “In the face of economic realities, you don’t have the resources to fight the market forever,” he said.