Sales of Chinese cars in Russia have hit fresh records after the country became the largest export destination for the Asian nation’s automakers when sanctions forced western brands to cut ties with Moscow.

Surging in Russian sales have helped Chinese carmakers at a time when Beijing faces higher tariffs on electric vehicle exports from Washington and Brussels — while engineering a rapid change in Russian auto culture.

“People are voting with their wallets,” said Ilya Frolov, a car blogger based in Moscow. “If you’re buying a car, your choice is either a [Russian-made] Lada or an extremely expensive European car brought in as a grey import, or a very well equipped and relatively cheap Chinese one.”

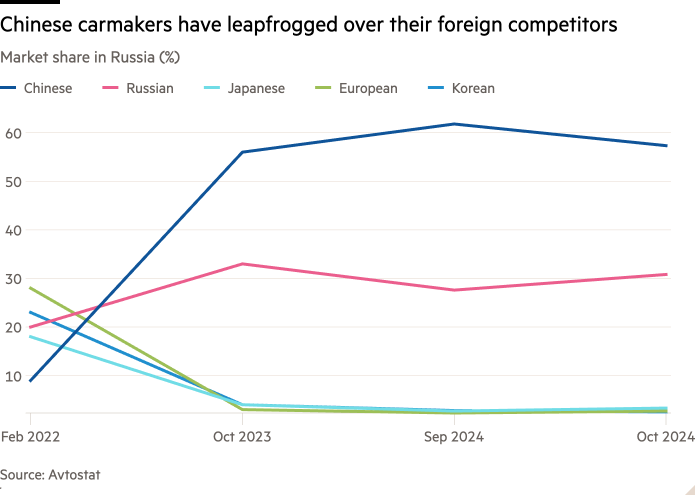

Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine sparked a sharp decline in sales of vehicles from the European, Korean and Japanese carmakers that previously dominated the country’s car market.

At the time of the full-scale invasion in February 2022, their brands made up 69 per cent of all sales, according to the Avtostat analytics agency. They now have a market share of just 8.5 per cent, while Chinese manufacturers’ share over the same period has risen from 9 per cent to 57 per cent.

In the first nine months of 2024, Russia was the largest export destination for Chinese-built cars, with the volume reaching 849,951 vehicles, according to data from the China Passenger Car Association, an industry group. The second largest destination, Mexico, imported less than half that number.

“China’s stellar auto export growth in recent years mainly relies on contributions from the Russian market,” said Cui Dongshu, general secretary of the CPCA. “Dramatic fluctuations and changes in the competitive landscape of Russia’s auto market have provided Chinese car companies with ample selling opportunities and huge profits.”

About 90 per cent of the Chinese vehicles being sold into Russia have internal combustion engines, though more than 15,000 cars manufactured by Li Auto, an electric vehicle maker specialising in spacious hybrid SUVs, were sold in Russia in the first eight months of 2024.

The expansion of China’s presence has been so big that not only customers but industry professionals have rushed to the new companies.

“Almost everyone [who used to work for western companies] is now employed by Chinese ones,” said Vadim Gorzhankin, the Moscow-based director of PR agency Krasnoe Slovo, which works with the car industry. “At first, we knew close to nothing about who these producers were, how to work with them, or even how to pronounce their brand names.”

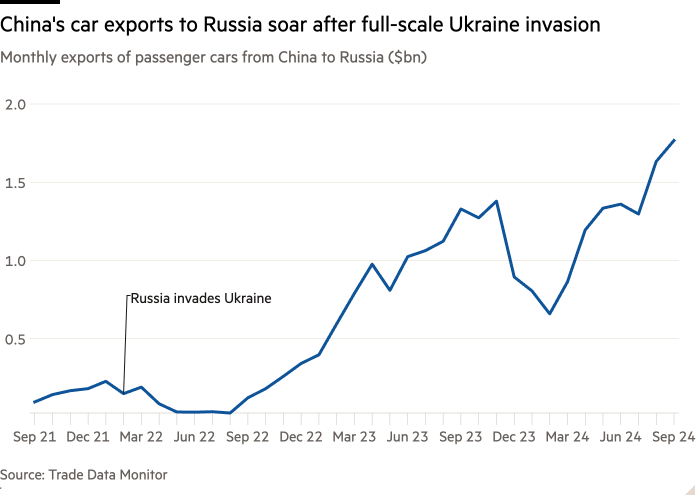

Chinese customs data show its carmakers exported $1.8bn-worth of cars to Russia in September, the most recent month for which complete figures are available, compared with $96mn in the same month in 2021.

While unofficial car dealers still wheel familiar western brands into the country through parallel import routes, high-price tags have put the brakes on their established customer base.

In Germany, drivers can buy a BMW X5 30d for about $95,000, according to the official company website. Prices for the same model range from $152,000 to $203,000 in Russia, according to the Auto.ru online marketplace.

A comparable Chinese-made Exeed VX costs about $56,000. Its manufacturer Chery is one of the best-selling brands, along with Great Wall Motor and Geely.

Some Chinese automakers have been tight-lipped about their involvement in Russia, attributing the growing presence of their cars on the country’s streets to a grey market operated by parallel traders.

Zeekr, an EV brand carved out of Geely, said in a statement that it has never appointed any dealers or distributors within the Russian Federation. “The few vehicles being seen in the Russian market [are] an individual behaviour,” the New York-listed company added.

Li Xiang, founder of Nasdaq-listed Li Auto, wrote in a social media post last year that the company did not “have any representatives overseas”, though he added that the company could not limit “demand” for private parallel exports shipped to Central Asia and the Middle East.

Frolov, the car blogger, ditched his Mercedes CLA and bought a grey import of a Zeekr X, retailing at $46,161, which can make it out of a tight parking spot at the tap of a button on his phone — a feature similar to that of the BMW 7 Series.

He said he was sold on the “wow factor” offered by Chinese producers, noting that the Huawei-backed Aito M9 has a pull-down screen similar to BMW’s luxury i7 that can project films for passengers in the back seat. “This car is a spaceship compared to a Rolls-Royce, which doesn’t have any of that fun stuff,” he said. “It has a very conservative design, small screens.”

The cars’ only fault is they are more vulnerable to theft, Frolov said. “There is less crime in China, so they don’t have the same security standards.”

Not all Russian drivers are pleased, however.

A union of Russian taxi drivers in October complained to Russian newspaper Kommersant about problems the industry has experienced since switching to cheaper models of Chinese cars.

Taxi drivers claim the Chinese vehicles often have to be written off after being driven 150,000km, while European and Korean brands used to last for up to 300,000km. Obtaining spare parts for repairs can also take a long time, the union noted.

China’s increasing dominance has also angered some domestic producers — especially those that have had to funnel more of their resources towards arms production.

Sergei Chemezov, the chief of Russia’s most powerful weapons maker Rostec, has called on the state to impose “protective measures” on Chinese vehicles. His company has a stake in Russia’s largest car manufacturer, Avtovaz, makers of Lada, which in September said its share of the market was likely to drop to 25 per cent following the surge in sales of Chinese vehicles.

The country’s car manufacturers have been hard hit by sanctions, which have limited access to western parts and technology. To compensate, they too have often turned to China.

Earlier this year, Russian prime minister Mikhail Mishustin hit out at a man who showed the new Volga model at a business conference, after it emerged that the vehicle’s steering wheel was made in China.

“Where is your steering wheel made? Chinese? I want the steering wheel to be Russian. It’s not as difficult as localising the gearbox and all the other elements,” the premier was reported by RBC, a business newspaper, as saying.

The trading relationship between Russia and China is lopsided. China, already the Kremlin’s top trading partner before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, now accounts for more than half of all official exports to Russia, according to Trade Data Monitor. In September, just 5 per cent of China’s total imports came from Russia.

“The direction of travel is very much towards Russia being more dependent on China,” said John Kennedy, expert on Russia at Rand Europe research institute.

“There is obviously a geostrategic partnership between China and Russia,” Ilaria Mazzocco, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “But there are also commercial interests developing, and likely very entrepreneurial actors on the Chinese side that are taking advantage of how the market has changed in Russia.”

Analysts believe the growing volume of trade between Russia and China could make it harder to spot Moscow’s shadow imports of sanctioned goods, which in the past stood out in the trade data of smaller transit countries.

Immediately after the full-scale invasion, “everyone quickly understood that Russia evades sanctions through former Soviet countries”, said Alexandra Prokopenko, fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Centre. “But China trades in such high volumes and with such opaque statistics that no one understands anything. A lot of things can be hidden.”

Additional reporting by Chris Cook