The US presidential election is finally here, and volatility is simultaneously everywhere and nowhere in financial markets.

This apparent contradiction stems from the unusually large spread that has opened up between two linked but different measures of market turbulence, neither of which on its own gives the full picture.

Realised volatility is backward-looking, calculated as the annualised standard deviation of an asset’s daily returns. By this measure, both the US stock and bond markets appear remarkably calm. Setting aside the recent tech-led sell-off and yesterday’s rally in Treasuries, both prices and yields have been rising steadily, rather than explosively.

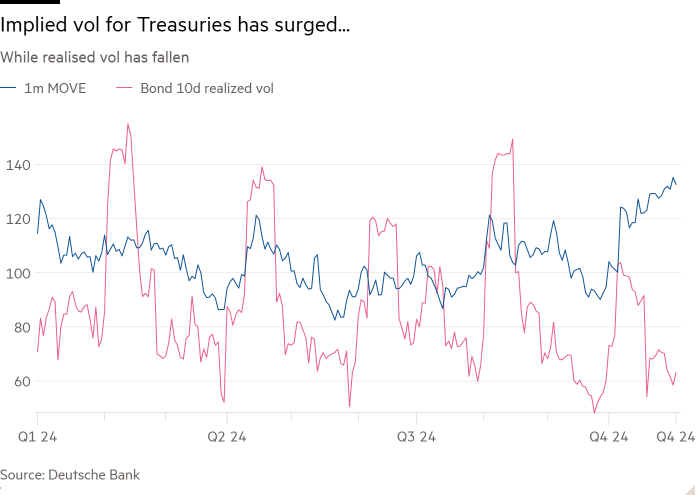

Implied volatility, in contrast, reflects option-based expectations of future swings. Here be dragons. The election remains on the proverbial knife’s edge, and then the Federal Reserve meets on November 7. No wonder MainFT is reporting that people are girding themselves for a hot mess.

Bankers, traders and investors are bracing themselves for a long stint of high volumes and increased volatility, particularly in bond and currency markets, ahead of Tuesday’s US presidential election.

With markets already pricing in potentially large swings across several asset classes, Wall Street banks have been preparing well in advance — with some pausing software updates and booking downtown hotel rooms for suburb-dwelling traders, to make sure they are ready to handle any unexpected moves on election night or throughout the rest of the week.

So why is there a discrepancy between realised and implied volatility? Firstly, a gap is entirely normal. Most of the time, implied vol > realised vol, as Ardea Investment Management explains in a handy note:

Intuitively this makes sense because a rational option seller would need to be enticed by a risk premium to compensate for taking the negatively asymmetric downside risk inherent in selling options.

On the other side, option buyers are willing to pay this risk premium because they are getting insurance-like protection against large market movements that might hurt their portfolios.

But ahead of the election, this spread — or volatility risk premium — has turned from a crack into a chasm.

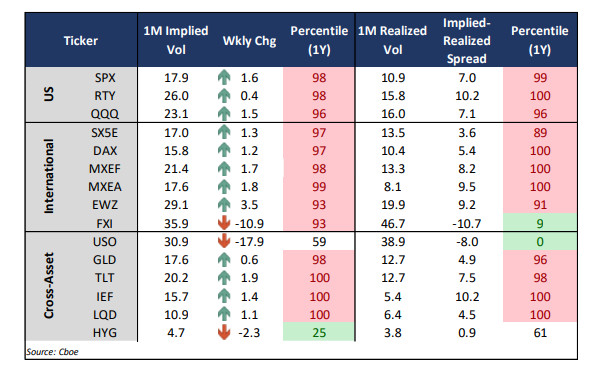

According to Deutsche Bank, the VIX premium relative to 30-day realised S&P 500 volatility currently ranks in the 91st percentile since 2010:

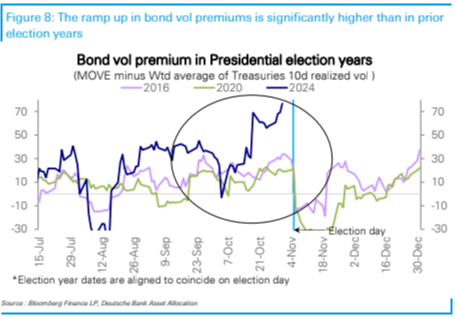

The spread between realised and implied volatility for US government debt is more extreme. The premium of ICE’s Move index to 10-day realised Treasury volatility ranks in the 99th percentile since 2010.

If the stock market is treating the election “like a typical [jobs] report,” one US portfolio manager told us, “there’s a perception that it’s become almost a once-in-a-generation event” for fixed income.

This checks out: if growth and inflation were to resurge in a red-sweep scenario, as some analysts predict they might, there would be far more uncertainty in terms of Fed guidance. Which means more volatility in rates.

[High-res version]

Similar if less extreme spreads are visible in the gold market and for currencies including the Mexican peso and the euro, as MainFT’s Will Schmitt and Nicholas Megaw covered last week.

Some of this gap between realised and implied vol betrays an understandable rush for hedges around the election.

Traders expect implied volatility to collapse (and equities to rally) once we know with certainty who won the election. “We’ve seen pretty rampant Vix put activity [recently]”, says Maxwell Grinacoff, US equity derivatives strategist at UBS, who’s been loading-up on December Vix puts himself.

But the withdrawal of volatility supply matters just as much, argues Dean Curnutt, chief executive of Macro Risk Advisors. As he told FTAV:

Because the election is so uncertain, no one is there to underwrite the dysfunction of the US political system. You really have to nudge someone to sell options that expire on November 6. This removal of supply has put upward pressure on the clearing price.

. . . . No one wants to be short the option, because you can’t analyse it. And there’s no point being a hero on something you can’t understand.

Basically, the price of insuring against sharp market movements is climbing more because of a reluctance to sell the insurance than it is for rising outright demand. And because the insurance is now so expensive, even if you’re right, the cost of the trade might outstrip any gain you make.

When a market-maker sells an option, it’s betting that the premium it pockets will be greater than the cost of hedging the trade. When you buy an option, you’re betting that the gain you make will exceed the premiums you’re forking out.

But when volatility goes from sleepy to violent extremely quickly, banks need to hedge just as fast, and that can become egregiously expensive or even impossible. That means the prices they quote around obviously risky events — if they quote at all — might be stupidly bad.

It’s like a bunch of insurers have decided to stop selling house insurance in an earthquake-prone neighbourhood, and the remaining players have jacked up prices — it might just be cheaper to pay for any rebuild yourself.

So far we’ve focused on implied volatility. But when it comes to the cost of the hedging strategies employed by option sellers, realised volatility is just as important, as Curnutt once again explains:

The cost of the hedging strategy [going long or short shares in the underlying asset] is very much about how much the stock moves.

Suppose I sold an option for $5 and the stock never moved. I would never have to re-hedge the position and I could bank all of the $5.

If instead, the stock moves wildly, I am going to lose a lot of money chasing the hedge and will likely lose money on the trade, even netted for the $5 I got paid to sell the option.

Realised volatility is the “earnings engine” for buyers’ long options strategies, Curnutt says, in that when it’s high it creates profits on hedging strategies that allow investors to pay more for options.

But when realised volatility is really low, as it is today (in stocks this is partly a product of low intra-index correlation, which isn’t unusual during earnings season when individual stocks/sectors zig idiosyncratically while others zag), investors have less to spend on their options of choice. All of which tends to lead to a pretty consistent relationship between realised vol and the VIX/MOVE.

Except, of course, for right now.