Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of Martin Sandbu’s Free Lunch newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every Thursday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

It took longer than I feared, but Ukraine fatigue is now clearly here. We see it in western yearning to give Russian President Vladimir Putin some of what he wants if Moscow will just stop the fighting (with little thought to Kyiv’s warning that it may just mean worse attacks in future). We see it, too, in how one finance ministry after another — first that of Germany, now France — is tempted to dial back its taxpayers’ support for Ukrainians’ defence of a liberal democracy inside the western fold.

Ukraine’s western friends have long qualified their support for the country with the twin insistence that they don’t want to be dragged into Russia’s war on it and that Russia can’t be defeated. This involves two profound mistakes. One is failing to see that the west is already deeply embroiled in the war, even if not on the battlefield. As officials in many western countries have pointed out (including the UK and most recently Ireland), Russia is waging hybrid and informational warfare on western territory. The other is that the belief in Russian invincibility is a self-fulfilling prophecy, as both political and military experts have pointed out.

This amounts to an unwillingness to confront Russia’s aggression in earnest. That has long been evident in the west’s too-slow contribution of weapons and the authorisation to use them to their full potential. But it is also the case — if less noticed — in the west’s halfhearted commitment to the non-military measures it does take, above all the tools of economic coercion.

Reserves immobilisation, travel bans, asset freezes, export controls and other trade sanctions are all part of the economic arsenal that has been deployed to increase the costs to Russia. Among the most important are the sanctions on Russia’s seaborne oil trade. But it’s all much less forceful than the west is capable of. Today I examine recent news and analysis of the west’s actions to hamper Russian oil shipping. It illustrates a more general point: the west has much more non-military power at its disposal to push back Russia’s aggression than it chooses to use.

At the end of 2022, the western coalition of countries supporting Ukraine hit Russia’s oil trade with sanctions. While the EU had contemplated an outright ban for their residents to ship or service oil exports from Russia, under US pressure an exemption was made for servicing oil shipments sold below a price cap of $60 a barrel. That seemed to have the desired (by Washington) effect of reducing Moscow’s export earnings while keeping Russian oil flowing so as not to upset the global market. But it also encouraged Russian authorities to organise a fleet of oil tankers to avoid any contact with western service providers — a “shadow fleet” to circumvent the oil price cap.

The Kyiv School of Economics has long monitored the shadow fleet, and this week published a report setting out how big it has become and the danger it poses to coastal states, quite apart from how it helps finance Russia’s illegal war.

Here’s how the FT’s news story summarises the report:

In June 2024, 70 per cent of Russia’s seaborne oil was transported by the shadow fleet, which Russia is estimated to have spent $10bn assembling, according to the KSE. This included 89 per cent of Russia’s total crude oil shipments, most of which traded above the $60 per barrel price cap since mid-2023, and 38 per cent of Russia’s oil product exports.

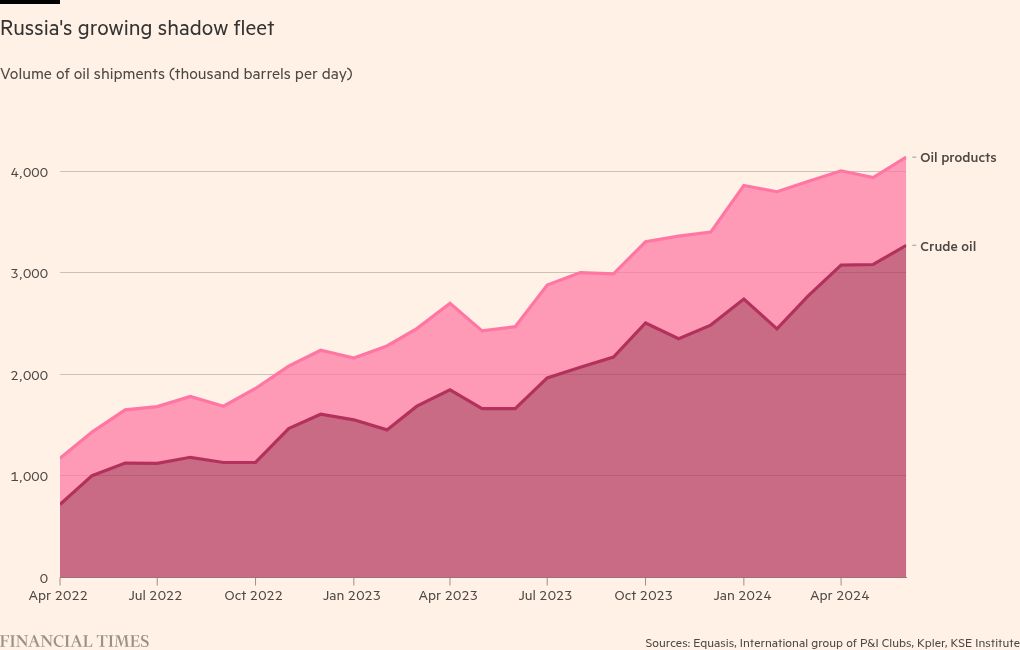

Russia’s shadow fleet now ships more than 4mn barrels of oil and oil products every day:

This is bad news on many levels. One is that it significantly reduces the effectiveness of the oil price cap. Another is that this sanctions circumvention seems to have taken place with the connivance of western helpers. My colleague Tom Wilson has produced a stunning investigation that lays bare how the build-up of the shadow fleet has been assisted by western enablers in law, accounting and finance.

But the most acute negative consequence is that an “environmental disaster is waiting to happen in European waters”, in the words of the KSE report. It calculates that three loaded vessels pass through the Danish straits and the English channel every day, and almost as many through the straits of Gibraltar and the Aegean Sea. Because these vessels are not adequately insured and serviced, they tend to be older and in a much less safe state than normal oil tankers. Already, shadow fleet vessels have been involved in collisions or instances of engine failure.

So can anything be done about this, or must western governments simply stand by and watch as Russia’s actions imperil them directly?

The challenge is the combination of two things: that international maritime law gives significant rights to free navigation, and that many western jurisdictions make no or limited use of “secondary” (extraterritorial) sanctions. This means a shadow fleet that manages to stay altogether disconnected from western jurisdictions is largely free to sail through their waters.

Even so, the experts show that there are a lot of legal, diplomatic and political tools available that Ukraine’s friends are not using to the full if at all. The main point, which was also made loudly to British government MPs at a side event to the Labour party’s conference last month, is that international law allows coastal states to demand more from both vessels and the flag states where they are registered.

Without even resorting to further sanctions, existing financial and environmental regulations could be used to reduce the problem. Craig Kennedy, a Harvard Russia expert who has proposed a “shadow-free zone”, argues that international maritime law allows coastal states to insist on insurance by transparent, reputable and financially solid insurers — which would be unavailable to the shadow fleet (they are supposedly insured in Russia). Noncompliant vessels could then be hit with sanctions individually, which would make it impracticable to use them because the buyers of the oil they carry do not want to risk being cut off from the US dollar system.

Other participants at the Labour conference side event proposed using environmental regulations more extensively, and imposing criminal liability for shipowners and crew who cause unacceptable environmental hazards. In addition, it could be helpful to expose the shadow fleet more effectively. Many shadow vessels go to extensive lengths to hide that they are shipping oil from Russia, as my colleagues have reported. More resources from western authorities into physical monitoring could change the calculus for western service providers and enablers to the front companies that own the ships simply by raising the risk and exposure related to possible sanctions designation. Information and transparency are powerful tools.

So why is not more being done? The simplest answer is a lack of resources and attention. That is understandable — but not forgivable, when a small amount of focus and money could make a big difference. The bigger point is that this half-heartedness applies across the whole range of economic sanctions, as the west dithers in giving Ukraine use of Moscow’s blocked central bank reserves or looks through its fingers while banned goods are blatantly smuggled to Russia.

The damage is not just that Russia’s aggression, as a result, receives resources the west could deny it. It is also that it signals so transparently that the west does not prioritise high enough its willingness to defeat Moscow. And that, more than weapons or money, is what encourages Putin to keep attacking Ukraine.

Other readables

Recommended newsletters for you

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Your essential guide to money, interest rates, inflation and what central banks are thinking. Sign up here

Unhedged — Robert Armstrong dissects the most important market trends and discusses how Wall Street’s best minds respond to them. Sign up here