Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Iris has a mystery to solve. Her brother has gone missing and there’s nobody better to crack the case than her: a brusque, gimlet-eyed reporter straight out of a hard-boiled detective novel. She is the star of Phoenix Springs, a new game with a strikingly original visual style that looks as if it has been screen-printed straight on to your TV.

Iris tracks her brother to a university campus where he once worked, and from there the trail gets complicated. You must examine a specific detail of a picture on the wall, inspect some meticulously alphabetised bookshelves, then click on an innocuous projector — twice — in order to progress. In short, stunning graphics, sharp writing and frustratingly oblique puzzles — all the hallmarks of a point-and-click adventure game.

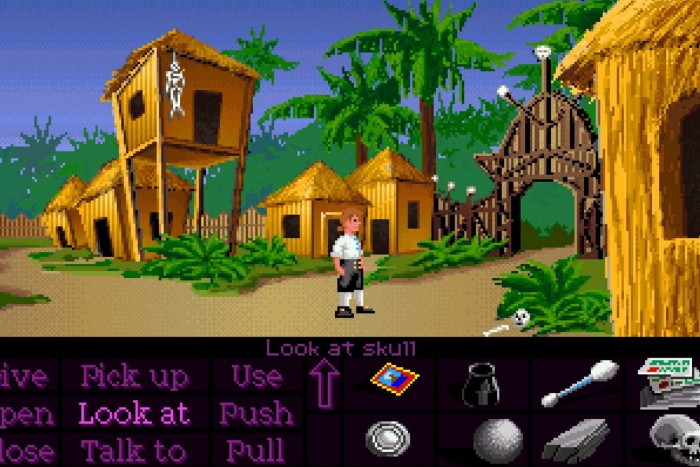

Such conventions might seem anachronistic to today’s players, but for a decade from the late 1980s, adventure titles were among the hottest in gaming, boasting storylines of unprecedented sophistication. Though they lacked combat, bosses or levelling up, they entertained with sharp writing, often in an absurdist comic mode, and puzzles that ranged in difficulty from breezy to console-smashingly obtuse.

Two companies defined the golden age of adventure games: Sierra, founded by husband and wife duo Ken and Roberta Williams, and LucasArts, a spin-off of George Lucas’s film studio. Sierra laid the genre’s groundwork with 1984’s King’s Quest, but it was LucasArts’ 1987 Maniac Mansion that showed its imaginative potential. Over the next decade, games such as the beloved Monkey Island series started incorporating music and detailed environments that made their worlds even more immersive and accessible. Their stories were mostly told with light-hearted wit, although in the 1990s more mature titles emerged, such as the dystopian Beneath a Steel Sky and the mysterious island adventure Myst, which sold 6mn copies.

By the mid-1990s, gaming technology was evolving. Early first-person shooters and action games were being released with rudimentary 3D graphics, and adventure games, with their pixel art, gentle pacing and lack of multiplayer, started to feel dated. Sierra was bought out and its original studios shuttered. Though LucasArts released a glorious swan song in one of its final games, Grim Fandango, a voyage into Mexican folklore, the writing was on the wall for adventure games. By 2005, even Monkey Island creator Ron Gilbert found it impossible to pitch new adventure games to publishers, saying: “You’d get a better reaction by announcing that you have the plague.”

Yet almost two decades later, the genre has made an unexpected return. This is partly due to the nostalgia of older fans, who dedicated millions of dollars into crowdfunding campaigns for new adventure games created by the old guard. Gilbert made a return with Thimbleweed Park and a Return to Monkey Island that lived up to the original’s charm.

But a younger generation of developers has also recognised the format’s potential for narrative ambition. In The Sexy Brutale you explore a mansion stuck in a murderous time loop, while Pentiment is a 16th-century monastic mystery. Particularly impressive are Norco and Kentucky Route Zero, both games that boast writing of literary calibre and smartly blend sci-fi and magical realism to deliver razor-sharp social commentary.

In the case of Phoenix Springs, developer Calligram Studio has made judicious choices about where to innovate on the point-and-click formula and where to stick to tradition. Just like the classics of the early 1990s, here is a game that lets you go at your own pace and trusts your intelligence to find the answers to its riddles. It also assumes that players will enjoy poring carefully over its environments for clues — which is indeed a pleasure, given this is one of the most visually arresting games in recent memory.

Some aspects deviate from the familiar LucasArts mould, however. For one thing, there are no items in this game; instead you collect ideas, mental clues gleaned from observation and conversation that you combine to further your quest. It also deviates from the genre’s typical verbosity for a terse economy of language reminiscent of film noir.

As the game progresses and you reach the titular desert oasis, the story’s grip on reality starts to loosen, and you begin to question whether your protagonist is who she claims to be, or if any of it is real at all.

Beyond its mechanical changes to the formula, the most provocative move Phoenix Springs makes is to remain allusive in its answers, leaving its questions around bioethics and social collapse lingering in your mind long after the game is over. In small gestures, it shows how this beloved genre has been able to evolve. But in the conventions it upholds, it also proves that these old bones are still good, even after all this time.