Power-hungry artificial intelligence is consuming increasingly vast amounts of energy from the creaking US grid and threatening national efforts to tackle climate change, according to the latest expert forecasts.

Unprecedented energy demand, fuelled in part by expanding data centres for AI, combined with the slower-than-expected pace of renewable development and longer operating timelines for polluting coal plants, have prompted analysts to recast their models for cuts in greenhouse gas emissions.

The theme dominated discussions at Climate Week NYC, held on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly last week, where technology companies were more in focus than the fossil fuel companies behind pollution historically.

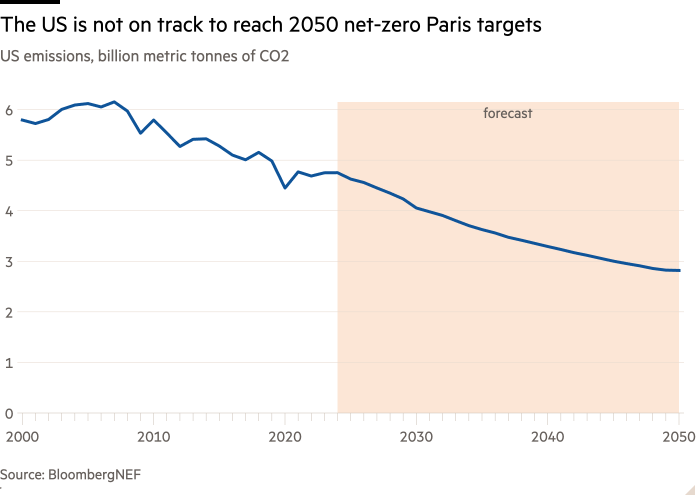

The latest report from BloombergNEF this week warned of the slower US progress on decarbonisation, predicting emissions would be reduced by as little as 34 per cent by 2030 from their 2005 levels.

The latest assessment puts the US trajectory even further from its national target to cut its emissions by 50-52 per cent by 2030 from 2005 levels, and to achieve net zero emissions by 2050, under its pledge to the Paris agreement.

“That’s not good by a long shot,” said Tara Narayanan, lead power analyst at BloombergNEF, calling the rise of AI power demand a “big disruption” to supply.

“It’s very much like that moment when you’re deep in the movie, and three different plot lines have been developed. You don’t know if it’s going to get resolved,” Narayanan said.

The lack of grid infrastructure is proving a big constraint to progress on the green energy transition not just in the US but around the world.

China is set for an unparalleled $800bn in spending the next six years to overcome strains on the energy system as it makes a rapid shift from coal power to renewable sources.

In the US, power demand remained virtually flat for two decades. Now forecasters such as consultancy group ICF expect it to rise 9 per cent by 2028 and nearly 20 per cent by 2033, citing data centre growth, the onshoring of manufacturing and electrification.

The Electric Power Research Institute predicted this year that data centres could double their share of US electricity consumption by the end of the decade.

But Jennifer Granholm, the US energy secretary, said she believed the country could still meet its net zero targets and handle the explosion in power demand, thanks to the near-$370bn green subsidies rolled out in the Inflation Reduction Act by Joe Biden’s administration.

“We have to be aggressive, but the momentum has begun, and it is not slowing down,” Granholm told the Financial Times.

Renewable project developers say the generation of green energy to meet the historic levels of demand is hampered by the fact that it can take up to half a decade to bring new supply online due to permitting and grid rollout delays.

“The need of the hour is to balance this,” said Sandhya Ganapathy, chief executive of EDP Renewables North America. “Unfortunately we may not have the [renewable] projects at the pace that is required.”

The proliferation of AI data centres has led to a race among Big Tech companies to find sources of low-emission round-the-clock power.

Last week, Constellation Energy and Microsoft signed a 20-year deal to reopen the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Pennsylvania, the site of the country’s most serious nuclear accident.

Expectations for higher electricity demand have also led to US operators delaying coal-fired plant retirements. S&P Global Commodity Insights has revised its expectations for coal plant shutdowns by the end of the decade by 40 per cent, even as renewable energy ramps up.

“The way things are going right now, it is very hard to imagine the US electricity system being carbon-free by 2035,” said Akshat Kasliwal, a power expert at PA Consulting. “We’re farther off from that target relative to where we were, call it three, four years ago.”

Pedro Pizarro, chief executive of Edison International, a public utility, said the surge in demand meant that gas power stations would also be required to remain in the energy mix for longer to ensure reliability of supply. Gas is mainly made of the potent warming methane molecule, which retains more heat than carbon dioxide but is shorter-lived in the atmosphere.

“We are not a gas company . . . We do not have a dog in the hunt of trying to keep gas around,” Pizarro said. “We, the industry, need to make sure that we have a system that’s reliable, resilient, given more weather extremes, as affordable as possible.”

The US has no shortage of renewables capacity, however. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory estimates that nearly 1.5 terawatts of generation capacity is waiting to be connected to the grid, enough to more than double the size of the country’s electricity system.

But projects built last year faced five years before they could get grid connection, and a shortage of transmission lines makes it difficult to transport green energy from distant generation sites to centres of demand.

Research firm Rhodium Group found that if data centre demand nearly tripled by 2035, and developers struggle to install new wind and solar, power sector emissions could be more than 56 per cent higher than forecast in its moderate emissions outlook.

However, the steep projections could also become much more muted as data centres become more efficient, tech group executives argue, and the wider adoption of AI reduces energy consumption by improving daily operations.

“Although it consumes energy to train the models, the models that are created will do the work much more energy efficiently,” said Jensen Huang, chief executive of Nvidia, the fastest-growing AI chipmaker, at the Bipartisan Policy Center on Friday. “The energy efficiency and the productivity gains that we’ll get from [AI] . . . is going to be incredible.”

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here