Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Much has been written about the deteriorating mental health of young people in recent years; survey after survey finds reported rates of depression, anxiety and other mental and behavioural disorders rising in teens and young adults.

For all the headlines, there have been several thoughtful challenges to this narrative. One is that shifts in the language used to talk about mental health mean subtle changes in survey wording can produce dramatically different trends. Another is that while young people may now be more likely to say they feel sad or worried, this has not generally been matched by an increase in more concrete markers of distress.

But two sources of economic data that have been underutilised in this debate suggest the deterioration is quite real.

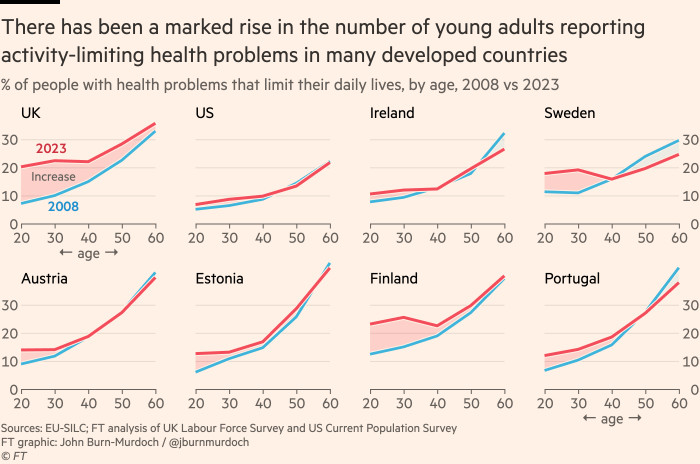

The first is labour force surveys, which have the advantage of having used the same wording in questions about illness for decades, specifying that they refer to conditions that materially limit someone’s ability to work or function day to day. Wide differences in employment rates between those who respond “yes” and “no” to these questions show that they are measuring something real.

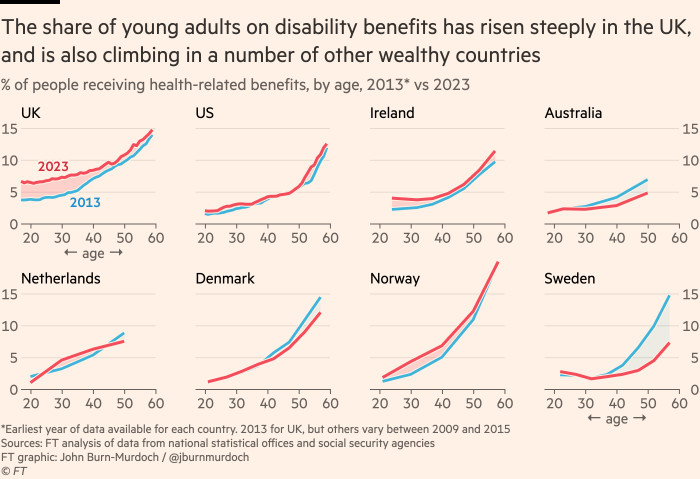

And the second is data on disability and incapacity benefits received by people of different age groups, which capture something much more tangible than self-reported health.

Using harmonised labour force surveys from across the west, I find that the age curve of activity-limiting health conditions has flattened considerably in many countries including the UK, US, Ireland and Sweden. Rates of disability have risen markedly among people in their twenties and thirties, but seen little change among older groups.

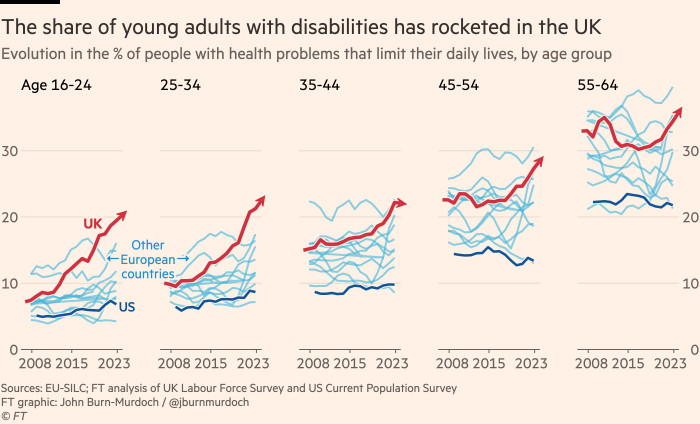

Few countries have seen as sharp an increase in young adult ill health as the UK, where the share of 16- to 24-year-olds reporting a health problem that reduces their ability to carry out day-to-day activities has almost tripled from 7 per cent in 2008 to 20 per cent today.

Importantly, data on health-related benefits shows very similar patterns. Extending two recent pieces of work by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, I find that awards of health-related benefits show strikingly similar patterns, with the receipt of disability benefits among young adults rising in several countries, led by the UK and Ireland. But there is little change — or even a reduction — further up the age distribution.

In several countries that provide detailed data, we can see that the rise in young adult disability benefits is driven by upticks in claims related to mental health. Importantly, IFS research finds that, in the UK at least, rates of claims being accepted have not changed, meaning this is not about increasingly lenient social security systems, but about rises in the number of people feeling the need to seek support.

The benefits data is also significant because it captures a much more severely affected group of people than those simply ticking boxes on surveys. One common pushback when discussing self-reported disability is to point out that the rise in prevalence of mental ill health has been matched by a rise in employment among the ill, suggesting we may be looking more at diagnostic inflation than a real deterioration.

But that argument falls flat when applied to the rise in disability benefits, where employment rates among those receiving health-related welfare payments have barely budged in the past decade despite considerable growth in the size of this group. People do not typically sign on as disabled lightly — nor is it typically a temporary status.

To be clear, some of the country-to-country differences in disability benefit receipts will be shaped by differences in how those systems are designed and operate. But the direction of travel within countries, and its similarity to the data on activity-limiting health conditions, suggests the deterioration of mental health among young adults is very real and is increasingly acting as an economic drag.

Reversing the trend will be much harder than identifying it. The causes that led us here are still being argued, and there is mounting evidence that some efforts to improve mental health may end up worsening it.

But with growing numbers of people who should have bright futures ahead of them turning to the welfare system in desperation, the challenge has never been more urgent.

[email protected], @jburnmurdoch

Data sources and methodology

Rates of activity-limiting disability: figures are from EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) as well as original analysis of the UK Labour Force Survey and the US Current Population Survey. People with activity-limiting disabilities are those who say their health conditions or illnesses reduce their ability to carry out day-to-day activities to some or a severe degree (Europe & UK) and in the US those who report a health problem or a disability that prevents them from working or which limits the kind or amount of work they are able to do.

Health-related benefits: building on two pieces of prior work from the IFS, data were gathered directly from national statistics offices and social security agencies where age breakdowns were available. Where figures were not available in percentage terms, population estimates were used to convert counts into rates. Country-specific details are given below.

• UK: disability or incapacity benefits, via DWP Stat-Xplore benefit combination tables

• US: social security disability insurance or supplementary security income, via CPS ASEC at IPUMS

• Ireland: disability allowance or invalidity pension, via Department of Social Protection

• Australia: disability support pension, via Australian Institute for Health and Welfare

• Canada: Canadian Pension Plan disability benefit, via Canadian open government portal

• Denmark: disability pension, via Statbank Denmark (tables PEN121, PEN123)

• Norway: disability benefit, via Statbank Norway (table 11715)

• Sweden: disability benefit, via Swedish social insurance agency