The future of the Murdoch media dynasty, a powerful empire that has shaped conservative politics across the English-speaking world for decades, is about to be hashed out in an unlikely venue: a nondescript probate court in Reno, Nevada.

Surrounded by parking lots and across the road from a business named “Bail Bonds Unlimited”, it is this courthouse in downtown Reno where Rupert Murdoch and his eldest son Lachlan are set to face off against three of his other children: James, Elisabeth and Prudence.

Murdoch, 93, wants to change the trust he set up in 1999 which grants each of the four equal voting power over the family businesses after he dies. His younger children from his third marriage, Grace and Chloe, have no such voting rights.

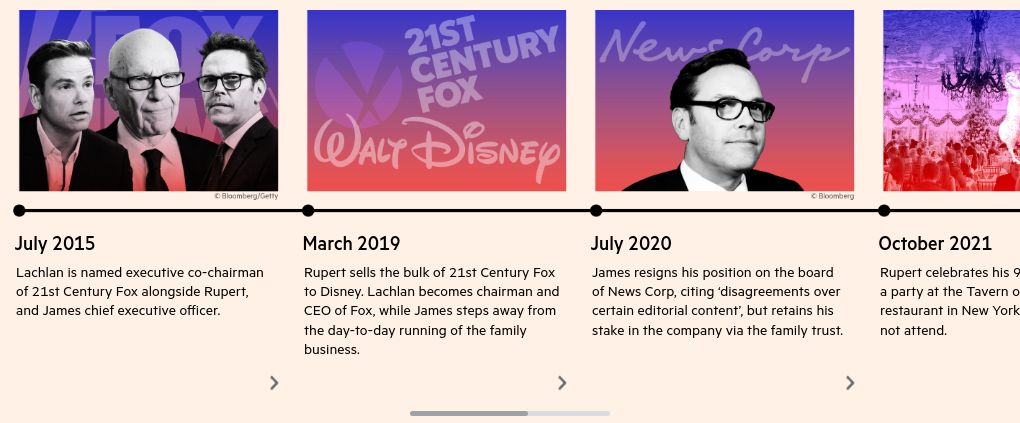

It is the latest move by the media titan to cement the long-term future of his news outlets, which include Fox News, The New York Post, The Wall Street Journal in the US and The Sun and The Times in the UK. Last September he consolidated control of his publicly traded companies — Fox and News Corp — under Lachlan, and announced his own semi-retirement.

But Murdoch also moved last year to overhaul the family trust to give Lachlan — whose political views are close to those of his father — full control of voting power and decision-making upon his death, according to several people familiar with the matter. The trust has large stakes in both Fox and News Corp.

Recipe for succession

The move blindsided Prudence, Elisabeth and James, say people familiar with the situation, and left them infuriated. One person close to the siblings described it as “entirely out of the blue”.

James Murdoch, who is estranged from his father in part over their divergent political views, has long been trying to rally his two older sisters to join him in changing the direction of the family’s news outlets once Rupert Murdoch dies.

It was never clear whether Elisabeth or Prudence had much appetite for such an effort, say several people familiar with the matter. But that changed when their father surprised them with the trust proposal.

“Was James trying to rally them to be a bloc? Yes. That’s what set Rupert and Lachlan off,” says another person who has worked with the Murdochs. “What Rupert and Lachlan have done, it did unite them. And so now it’s a real thing, as opposed to just James wanting it to be a real thing.”

Now the two sides of the family are set to face off in a Nevada court over changes to the irrevocable trust, an arrangement that is designed to be harder for the grantor to alter or revoke.

The competing arguments have already been made in voluminous secret filings, and court hearings are set to begin on September 16. The job of deciding whether Murdoch’s proposed changes to the trust are in good faith and for the benefit of all his children falls to the county probate commissioner.

At stake is not just the family fortune but also the future direction of the global news entities that have had a profound influence on politics in the US, the UK and Australia for the past 40 years. Fox News, in particular, has served as a lodestar of the American right, and played a key role in the political ascent of Donald Trump.

Longtime Murdoch watchers say that this may finally be the “end game” for a dynasty whose drama and divisions have run for several decades and helped inspire the hit HBO series Succession. After this, the rifts that have torn the family apart may themselves be irrevocable.

Rupert’s wedding in June — his fifth — was attended by Lachlan. But James, Elisabeth and Prudence were absent. “Lachlan and James I can’t imagine will have a relationship at all after this,” says a former lieutenant of Rupert. “In terms of the family, this might be it.”

The high-stakes battle is taking place in total secrecy, which is by design. Nevada has long been deemed favourable to those with large fortunes seeking to keep trust proceedings secret, as it has some of the strictest confidentiality laws in the US.

The statute was made even more favourable to the privacy-obsessed in an update passed last year, around the time the Murdoch suit was filed. Nevada trustees are not even required to “provide an account [of the financial condition of the trust] to a person who has been eliminated as a beneficiary”, never mind the broader public.

Unlike in other jurisdictions, Nevada also tends to seal court proceedings in probate matters by default. Activists and a coalition of media companies have been pressing for more public access to the proceedings, thus far without success.

There have been discussions about a settlement, say people familiar with the matter, with speculation among investors that Rupert could hand one of his less-coveted chess pieces, such as HarperCollins, to the other siblings in his quest to preserve a conservative slant for Fox News under Lachlan. “Rupert’s always been prepared to pay the price for something he wants,” notes the former lieutenant.

But these talks have not advanced, and family members on both sides are set to appear in Nevada next week, these people say.

A person close to one of the three siblings says that they believe their father’s motives are clear. “He wants to safeguard the future rightwing direction of his empire,” the person says.

Murdoch could argue in court that disputes between his children would bring instability to the businesses, or that changing their political direction could damage their popularity, which could hit the businesses financially, making it a matter of shareholders’ interest. “Do I want to see the boat get rocked? No,” says one News Corp shareholder.

If James and his sisters win, another News Corp shareholder speculates that their father might end up selling assets to avoid handing control to them. “The guy is 93 years old and doesn’t speak to his son . . . so why would [he] just gift him this sprawling media empire?” the shareholder says.

That might suit some investors. While shares in Fox and News Corp have gained some 24 per cent and 30 per cent, respectively, over the past year, News Corp shareholders have long agitated for changes to “unlock value”, such as selling off parts of the business.

On Monday, activist investor Starboard submitted a proposal to end the dual-class structure that gives the Murdoch family control of News Corp, arguing that disagreement among the children “could be paralysing” and “represents a risk to shareholders”.

“There are no reasonable arguments to extend supervoting rights and de facto control to the inheritors of a founder,” Starboard said in a shareholder letter. The Murdoch trust owns about 14 per cent of News Corp’s equity but controls 41 per cent of the voting power at the group.

The legal battle has spurred talk among analysts and rival executives about whether a break up of the business might still be a way to resolve the family feud, with parts being divided among the siblings and even to other investors.

Any move to hive off assets to the opposing siblings would be complicated, according to rival media executives, given the need for shareholder approval. One adds that if Murdoch were successful in changing the family trust, then he would in effect be forcing these changes also on the wider shareholder base, which could prove contentious. “He is tying everyone to this outcome,” they say.

Mathias Döpfner’s Axel Springer would be interested in newspaper titles such as The Wall Street Journal should it come up for sale, according to people close to the situation.

In response to a request for comment from the FT, a spokesperson for the newspaper provided a rare statement directly from Rupert Murdoch: “Dow Jones and The Wall Street Journal are absolutely not for sale. There is simply no truth whatsoever to this unfounded rumour.”

“Rupert has always struggled with letting go of anything,” says one person who has had close dealings with the family. “This is an elderly gentleman’s attempt to guard the rightwing agenda with the help of an acquiescent son.”

If Murdoch’s media empire is at risk of being permanently broken up, so too is his family.

People close to the siblings say that Elisabeth, in particular, is very upset at her father’s actions. She had previously sought to be a bridge between the different camps, often spending time with her father when at their family homes in the UK and talking fondly of him in public.

“She feels like she’s been the loyal daughter, even though obviously [she] disagreed on a lot of things, but she stayed very personally loyal to her father, through his 90th birthday party and all that kind of stuff. And then, for that, she gets this. This was sprung on her,” says the former lieutenant.

There is hurt in particular that Murdoch’s move to alter the trust has breached the good-faith agreement with Anna Murdoch Mann, the mother of Elisabeth, Lachlan and James, who insisted on the arrangement when she divorced Rupert.

“This was not what the family had agreed. Anna could have taken half his money but said that she instead wanted the trust set up to protect the four children. It’s established in perpetuity,” says one person close to the warring siblings. “There is a lot of anger. It is not a happy family.”

Additional reporting by Christopher Grimes