Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Automobiles myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Auto loan default rates are among the most useless of economic indicators. But because a car is easier to imagine than a current account or a unit of labour, we keep getting excited about them anyway.

In 2017, Steve “Big Short” Eisman caused a lot of noise by saying he saw parallels between rising subprime autos delinquencies and the global financial crisis. Then came a pandemic, and a rash of “canary in the coal mine” type coverage as slumping US second-hand autos prices followed a sales boom born of surplus savings and existential boredom.

The theme looped back into view this week on a warning from Ally Financial, one of the big-four US auto lenders. Ally shares dropped 17 per cent on Tuesday after its CFO Russell Hutchinson told a Barclays conference that borrowers are “struggling with high inflation and cost of living, and now more recently, a weakening employment picture”. Delinquencies in July and August were “up about 20 basis points versus our expectations”, he said.

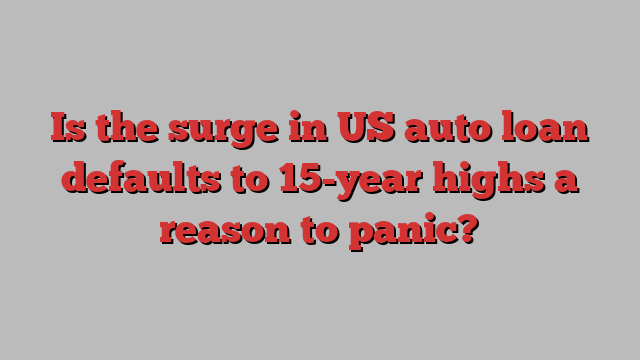

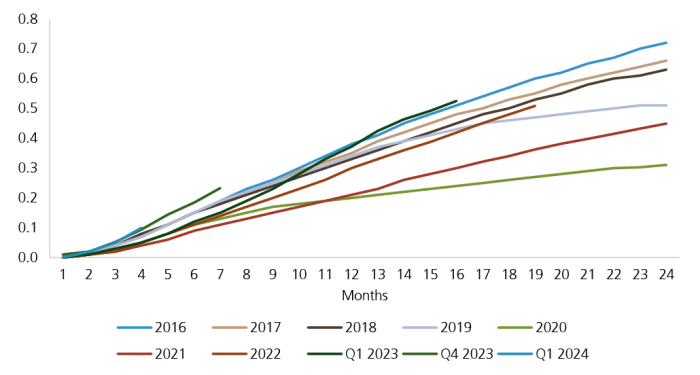

To be sure, US auto loan default rates are high right now. Graph from UBS:

Per the above data, the 60-day delinquency rate for subprime auto loans in July was the highest on record excluding 2009, up 0.1 percentage points to 5.98 per cent. But subprime only accounts for about 16 per cent of car loans.

A potentially bigger deal is that prime delinquencies have also moved into non-GFC record territory, up 0.1 percentage points to 0.62 per cent. That’s just 9 bips below the June 2009 peak.

Worried? UBS strategist Matthew Mish and team are not.

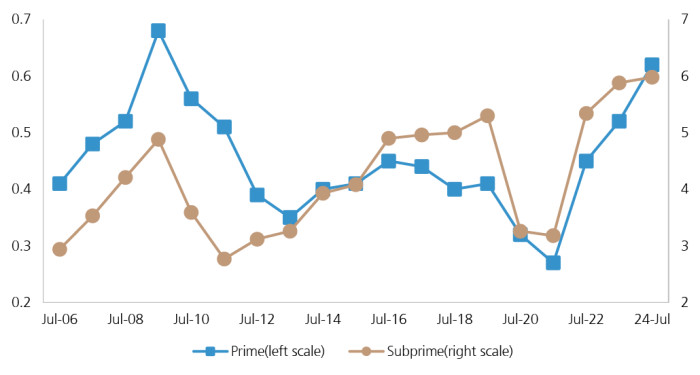

They point out that the rise in delinquencies doesn’t carry through to net loss rates. Households with good credit are choosing to resume payments before their car is towed. That wasn’t the case during the GFC:

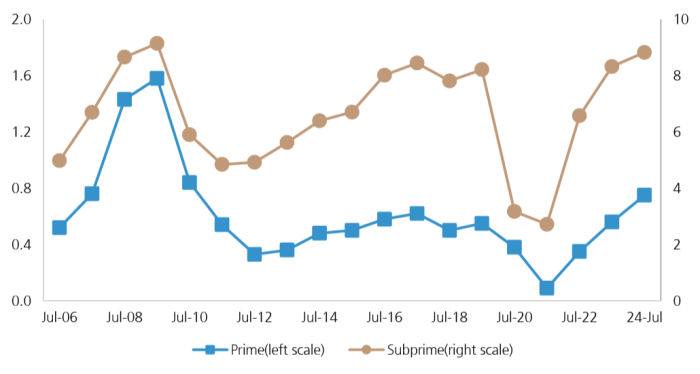

Second, investors are relaxed. Spreads on auto asset-backed securities (which track losses, not delinquencies) have widened a tad recently but remain approximately half the long-run average of 1.12 per cent.

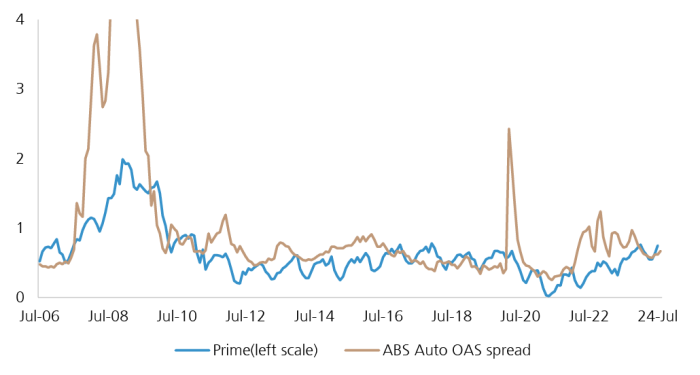

Third, defaults on recently written prime loans are only slightly worse than on the older vintages. Not enough data is available for July and August, so we can’t backtest what Ally has reported, but the earlier trends have been fairly benign:

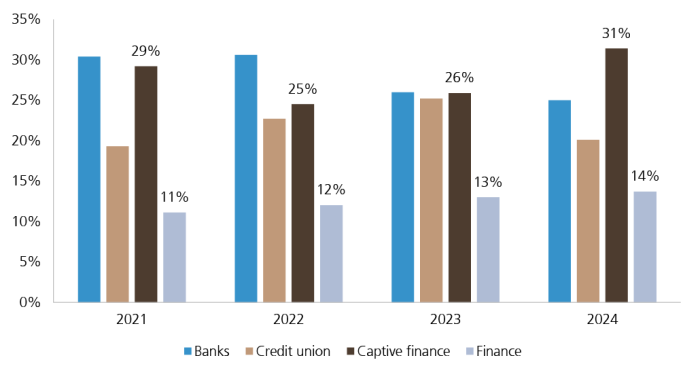

Fourth, auto debt is not like other debt. Captive finance (meaning the automaker writes the loan via a subsidiary) has grown rapidly to take about a third of the market. US banks and credit unions have been pulling back.

Auto loans account for just 4 per cent of total US bank loans. The market is too small and odd to cause GFC-style systemic problems.

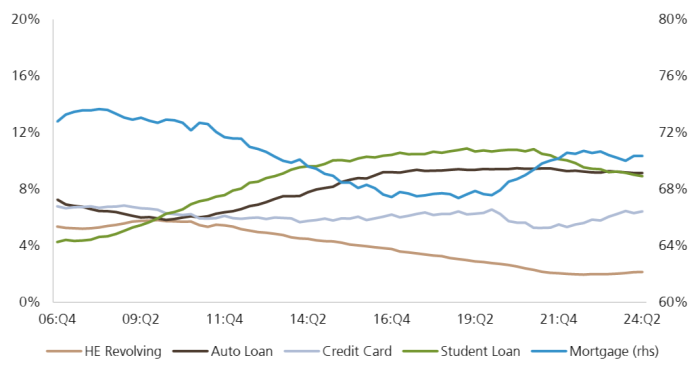

A car is a big expense for US consumers, however. At 9 per cent of household debt the auto loan on average the biggest non-mortgage credit cost, having recently edged ahead of student loans:

Maybe these worsening trends are not yet priced into specialist consumer lenders, particularly at the prime end of the market. Automakers, too, will have to keep fighting the temptation to hit quarterly numbers by relaxing lending standards. (We note apropos nothing that Tesla this week launched financing for US buyers of $0 down and 2.49 per cent APR.)

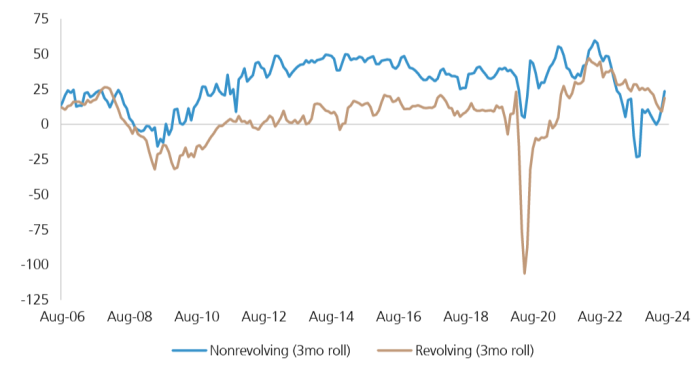

Importantly though, there’s not much evidence yet that broader US consumer credit growth is being impaired:

As usual, then, it’s probably nothing much to worry about. As you were.