Most people boarding a plane do not realise that the aircraft almost certainly does not belong to the airline whose logo is painted on the fuselage — and I should know: I own a small fraction of an Airbus A380 that is leased to Emirates.

In fact, the world’s largest owner of civil aircraft is Dublin-based AerCap, which employs accountants rather than pilots. What is more, the owner of the aeroplane usually does not own the engines. The airline will have a contract for engine services — say for 10 years — with an engine manufacturer, such as Rolls-Royce, which agrees to provide power and maintain or replace the engines during that time. However, Rolls-Royce does not own the engines, either. Ownership is normally passed on to a subsidiary, in this case jointly controlled by GATX, a company whose principal activity is leasing rail carts.

What about Amazon warehouses? They can be found all over the world; the name and logo on the side reminding you that Amazon is a corporation whose revenues and market capitalisation put it among the largest businesses in the world. But, most of these “fulfilment centres” are rented — the largest provider is the San Francisco-based Real Estate Investment Trust (Reit), Prologis. And whose are the goods inside? If you look at Amazon’s balance sheet, you will see that in the main you, or your credit card provider, have paid for your purchases before Amazon has paid the supplier. Most retailers employ similar practices.

The Industrial Revolution happened when wealthy individuals provided the capital to build textile mills and ironworks and controlled the businesses that operated from them. They attracted workers from the fields to provide unskilled or low skilled labour within these plants. There was a strong and clear tripartite link from personal wealth to ownership of the physical means of production to control of business and domination of labour. Robert Peel, father of the future prime minister of that name, was a wealthy farmer who built textile mills. Francis Cabot and John Lowell used their profits from privateering to establish plants in New England. For Karl Marx, that connection from wealth to the finance of plants to the exercise of authority represented the capitalist mode of production.

And that tripartite linkage continued to describe business into the 20th century. Henry Ford used the profits from the success of his Model T to build the world’s largest industrial plant at the River Rouge — you could have dropped Hyde Park and Central Park on to the site and still had room to spare. Ford insisted on control over every aspect of production. An area of Brazil is still known as Fordlandia after Henry’s attempt to source the rubber for the tyres on Ford cars from his own plantations. When I once commented that the English motor manufacturer William Morris insisted that Morris Motors fabricated everything in its cars except the owner’s manual, a historian friend advised me to check. Morris had indeed established the Nuffield Press to print instructions on how to use his cars.

Yet as finance and business became more complex, the link from wealth to ownership of the means of production to managerial authority eroded. Railways were funded by gathering the savings of individuals who might be part of the bourgeoisie but hardly qualified as capitalists — the Brontë sisters speculated in railway stocks from the parsonage at Haworth. And the growing complexity of production and its organisation created an ever-increasing role for professional career managers.

In the interwar years, companies such as General Motors and Imperial Chemical Industries came to dominate their economies, their ambition and self-confidence reflected in their titles. The 1950s and 1960s were the heyday of this managerial capitalism. The leaders of these companies exerted quiet political influence but maintained a low public profile. Gregory Peck played The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit, the epitome of the colourless corporate executive.

But 21st-century business looks very different. The man in the grey flannel suit has given way to the heroic CEO — the appointment of Brian Niccol (pictured in this paper with white jacket and no tie) has just added $20bn to the market value of Starbucks, a figure that makes his $113mn pay deal look relatively modest. Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg, founders of Amazon and Facebook respectively, are household names, and unimaginably rich. The connection now runs from control of business to personal wealth, not the other way round. And ownership of the means of production — the assembly lines of Ford and General Motors, the petrochemical plants of ICI — is no longer of central, or even very much, importance.

Twenty-first-century companies such as airlines and Amazon buy capital as a service from a specialist supplier as they buy electricity and water and security from a specialist supplier, and AerCap and Prologis exert no more influence over the conduct of their customers than do the suppliers of these other services. Pilots do not know who owns the plane they fly, Amazon employees do not know who owns the warehouse where they work, and they don’t know because it doesn’t matter to them.

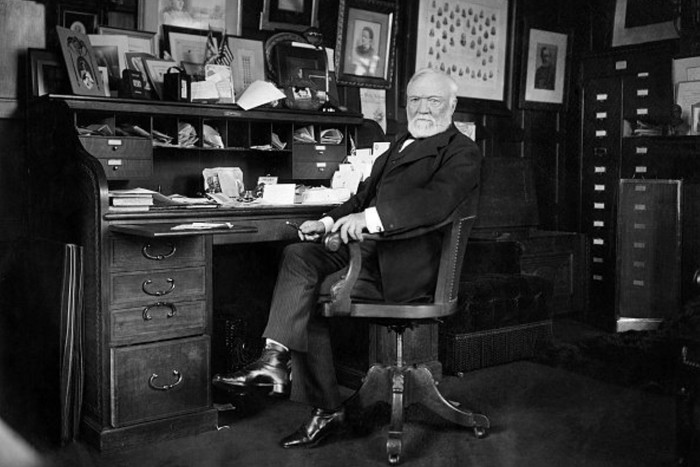

400The number of times greater that Jeff Bezos’ $200bn wealth is than Andrew Carnegie’s. Over the same period, US national income has risen only by a factor of 50

Both products and the means of production have dematerialised. For example, most of the smartphone’s functions were already available, but with one in your hand you no longer need a landline, camera, atlas, calculator, record player, plane or theatre ticket, or even a wallet. And Apple’s Cupertino campus is barely a tenth of the size of Henry Ford’s Dearborn complex — and most of the site’s surface is grass.

Apple is the epitome of the “hollow corporation”; it is less a manufacturer than a co-ordinator of activities mostly undertaken by others. The largest supplier of iPhone components is Samsung, Apple’s principal rival; assembly is the responsibility of the Chinese-based Foxconn; chips once came from Intel but, now designed by Apple, are manufactured by Taiwanese TSMC.

The coffee shop where Brian Niccol fervently hopes you will buy your Frappuccino may be rented by Starbucks from a Reit or operated by a franchisee; the franchise model offers branding and expertise to independent businesses and is now common in fast food, hotels and even global accountancy. On Google and on social media platforms like Facebook and TikTok, the consumers are also the producers. Airbnb and Uber are pure intermediaries. Henry Ford’s integrated assembly process from rubber to road is now only a memory from a distant era.

Yet at the same time as tangible capital has become incidental to business rather than central to its operation, the financial sector has grown in size and even more in remuneration. So who are the capitalists now?

The rentiers of early capitalism — the characters of Jane Austen novels, for example — have largely disappeared. Not altogether; Françoise Bettencourt Meyers, the L’Oréal heiress and archetypical capitalist for French economist Thomas Piketty, plays piano in her ample residence, and Alice Walton is a generous patron of the arts. But almost all the richest people in the world today are business founders, such as Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk. In Europe, France’s penchant for luxury goods makes Bernard Arnault, who built LVMH, the country’s richest man; Germany’s different tastes bestow the accolade on Dieter Schwarz, founder of discount retailer Lidl.

In an obvious sense, these men are successors to the “robber barons” of the Gilded Age, such as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller. Yet there is an important difference. Carnegie and Rockefeller owned steelworks and pipelines, directly or through their corporate vehicles, and took profits from these activities to finance their extravagant consumption and build private investments.

The wealth attributed to Bezos and Musk, however, is based on stock whose value is entirely dependent on a belief that Amazon and Tesla will make and distribute large profits at some future date. That hope has been sold to investors in the Magnificent Seven (Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, Tesla, Meta, Apple and Nvidia) and their smaller rivals — and may or may not be realised. Modern capital markets in effect allow that “a business should be able to declare profits at the moment of the creative act that would earn these profits”. The aspiration might be more commendable if the words were not those of Jeff Skilling, once more at home after serving 12 years in federal prison for his criminal activities while at Enron.

After Bezos, Amazon’s largest stockholders are BlackRock, State Street, and Vanguard. These asset managers are also the largest stockholders in Tesla, after Musk. They are also the largest stockholders in Prologis. And they are likely to be among the largest stockholders in most other companies you might think of. (The equity of AerCap is provided by a slightly different group of asset managers.)

BlackRock and its competitors are not beneficial owners, of course; they run index funds that invest in everything and also offer active management through pooled funds and on behalf of large institutional investors, such as endowments and pension funds. Some of these institutions are large direct investors in equities; organisations such as Norges Bank Investment Management, which manages the more than trillion-dollar sovereign wealth fund of Norway, and Calpers, which funds the pensions of California’s public employees.

But most providers of capital as a service, such as AerCap and Prologis, raise the bulk of their finance through loans from other financial institutions. The stock market has long ceased to be an important source of finance for business: its role is not to provide capital but to allow business founders to cash in — and out.

Whether the long chain of intermediation runs through shares or deposits, pension funds or mutual funds, at its end we find individuals. NBIM invests for the people of Norway; Calpers on behalf of the teachers, firefighters and police of the Golden State. Bank customers and insurance policyholders finance the loans to AerCap and Prologis. Few of these actual and prospective beneficiaries know how, or that, they have themselves funded the aeroplanes they fly in, or the Amazon warehouse that dispatches their goods.

Control of business, rather than control of territory, is today the source of extreme wealth. When Carnegie Steel became US Steel in 1901, Andrew Carnegie was worth about $500mn; but Tsar Nicholas II would have despised him as a pauper. Bezos’ $200bn today is 400 times greater than Carnegie’s but over the intervening century US national income has risen only by a factor of 50. But there are very few Bezoses or Carnegies. Wealth is today more widely distributed than before. This is not the same as saying wealth is more equally distributed. Many more people now have some wealth.

Several factors have contributed to this dispersion of wealth. One is the housing market: by the 1960s owner-occupation became the norm in most developed countries. And then low interest rates and planning restrictions resulted in house prices rising relative to most other economic variables.

The invention of retirement has had many economic as well as social consequences. At the beginning of the 20th century, life expectancy at birth in England was about 45. Most people died before reaching what would either now or then have been considered retirement age. And if they survived to the end of their working life, they rarely lived long thereafter. Today, someone aged 65 can expect to live for another 20 years and will have accumulated rights to state and private pensions to support their retirement.

And rising incomes have allowed people who would once lived from hand to mouth to accumulate some savings. Not long ago, most workers were paid on a weekly cycle and budgeted on the same cycle; today a smartphone gives instant and almost universal access to financial innovations from mutual funds to mobile banking which have transformed retail finance.

To see a modern capitalist, perhaps you should look in a mirror in the home you own. Or take a selfie.

Based on The Corporation in the 21st Century: Why (almost) everything we are told about business is wrong by John Kay (Profile, £25)