At shortly after 10am on Friday, with torrential rain lashing the doors and a potential $50bn takeover bid in the air, three people are queueing at the original Toyosu branch of 7-Eleven in Tokyo.

One of them is buying a croissant and coffee; one is buying a Yakult, a salmon roe rice ball and a limited edition bag of grape-flavoured fruit gums; one is buying a bag of cat treats. A batch of fried chicken emerges from the back of the store, carried by a woman wearing a jacket in the world-famous corporate livery of green, red and orange.

“I probably spend more money in 7-Eleven than in any other shop, they are just always there, they are part of life and the food has kept getting better,” says the coffee-and-croissant purchaser. “I heard they might be sold, but I don’t think that can happen, can it?”

It can, and to a foreign entity at that. The Canadian convenience store giant Alimentation Couche-Tard, best known for its Circle K brand, has approached 7-Eleven’s parent company Seven & i Holdings with an unsolicited — but so far friendly — buyout bid.

There is not yet a formal proposal for Seven & i’s shareholders to consider, but already many bankers, investors, lawyers and government officials are talking of it as the most important and transformative M&A deal Japan has ever seen.

Bankers talk excitedly of a “day zero” that, irrespective of the eventual outcome, could put a number of global household names in play for takeover. This is, in many respects, a battle for Japan and for its willingness to become a vibrant market for corporate control.

“I think the Couche-Tard bid accelerates and exposes everything,” says the manager of one of the world’s biggest event-driven investment funds and now a shareholder in Seven & i.

“The game is on now, and there is a good chance that Japan becomes the M&A deal centre of the world for the next 10 years.”

The history of Couche-Tard’s interest mirrors that of western investors in Japan more widely. It has courted the company on and off for two decades, but been deterred by a combination of factors. These include Japanese companies’ instinctive resistance to being acquired, the historic absence of governance pressure on them to put shareholder interests first and the ready availability of poison pills and other defence mechanisms.

Its target had been softened by two different activist investors — a relatively new phenomenon in Japan — who mounted noisy campaigns urging management to rationalise the group to improve returns.

The approach itself has been facilitated by shareholder-friendly M&A guidelines introduced last year by the Ministry of Economics, Trade and Industry (Meti), which all but oblige Japanese companies to consider bona fide takeover approaches rather than simply ignoring them.

But even in this new environment, there is now an open question over whether the government is ready to countenance a non-Japanese owner of Seven & i, while companies, in the absence of examples to the contrary, are able to convince a domestic audience that foreigners could never run such an intrinsically Japanese company better.

Convenience stores or konbini are the pinnacle of what Japan does best. They sell fresh bento, reasonably priced Cabernet Sauvignon, gelato, shirts, funeral offerings, cosmetics, metal dinosaur kits and concert tickets. Customers can pay their tax bills there, or do their banking.

They have strived to become indispensable, and won. Behind the scenes, the operation is powered by automation, robots, finely tuned supply chains and efficient distribution logistics.

“I think foreigners should be able to buy Japanese companies,” says the customer buying cat treats. “But I do not believe a foreigner could run this particular company.”

The 7-Eleven convenience store began life in Dallas, Texas, in 1927, even though the name itself wasn’t adopted for another two decades.

Executives at its parent company, Southland Corporation, were known as the “7-7-7” crowd because of their ability to work from 7am to 7pm, seven days a week.

Ito-Yokado, the forerunner company to Seven & i, struck a licensing agreement with Southland to develop the concept in Japan in 1973. After the US parent filed for bankruptcy, it seized the chance to take control of the whole group in 1991 — a time when angst in corporate America about Japanese technological, managerial and financial prowess was close to its peak.

Since then konbini have evolved into Japan’s most powerful conduit of consumption, temptation and retail innovation. After years of consolidation, the country now has three significant competitors: 7-Eleven, Family Mart and Lawson, who together control more than 50,000 stores in their home market.

Almost half of those are run by Seven & i, and pull in 22mn customers a day. The group also has convenience operations overseas, notably in the US, where in 2020 it agreed to spend $21bn in cash buying Speedway, the petrol station chain owned by oil refiner Marathon Petroleum.

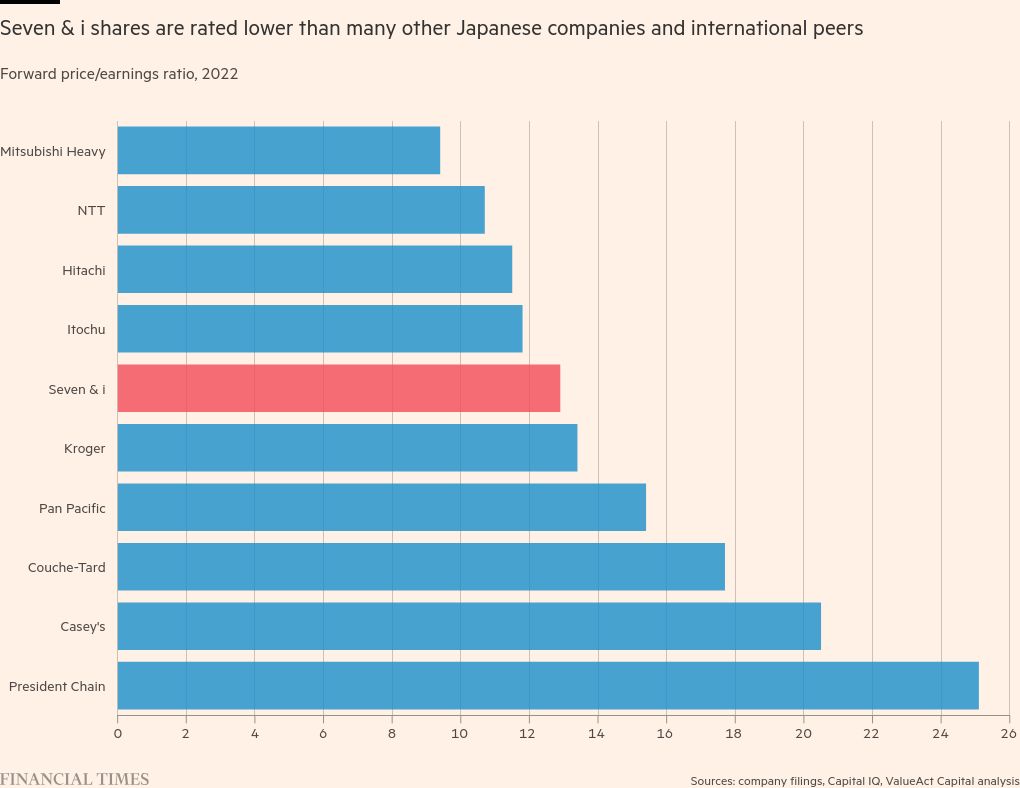

But as with many other Japanese corporations, domestic dominance and operational savoir-faire have not translated into shareholder returns. In many ways, say investors who have held the stock for years, Seven & i represents both the best of Japan and the worst.

Behind the core convenience store business sits a hinterland of supermarkets, restaurants and other often unrelated operations that have generated mixed returns and long looked ripe for sale.

An activist campaign by Dan Loeb’s Third Point hedge fund helped oust chair and chief executive Toshifumi Suzuki — once known as “the king of konbini” — in 2016, with Ryuichi Isaka taking over as chief executive.

Over the past few years Isaka has overhauled the company’s board, installing a progressive international chair, and sold off some non-core assets while promising to accelerate international expansion.

But these efforts have not been sufficient, say some investors. Alicia Ogawa, a board member at the Nippon Active Value Fund and an expert in Japanese governance reform, points out that many of the new non-executive board directors are not really independent, having come from suppliers or companies with deep ties to Seven & i.

Even allowing for the spike since Couche-Tard’s offer was made public, the company’s share price has lagged behind Japan’s benchmark Topix so far this year and over five years.

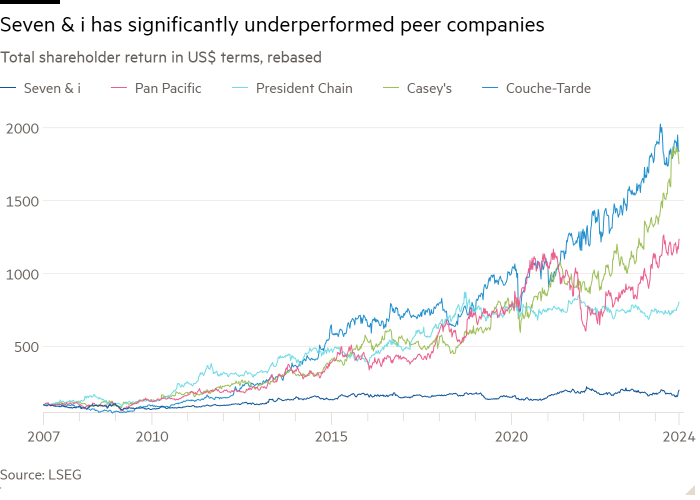

Benjamin Herrick, an investor in Seven & i with Artisan Partners, points out that since Isaka’s appointment, the company “has deployed $25bn in acquisitions, but its market capitalisation has done nothing in yen terms, and even less in dollar terms”.

“The total shareholder returns over that period are minus 1 per cent,” Herrick adds. “Over the same period, the total shareholder return for Couche-Tard is 191 per cent after deploying $12bn of capital.”

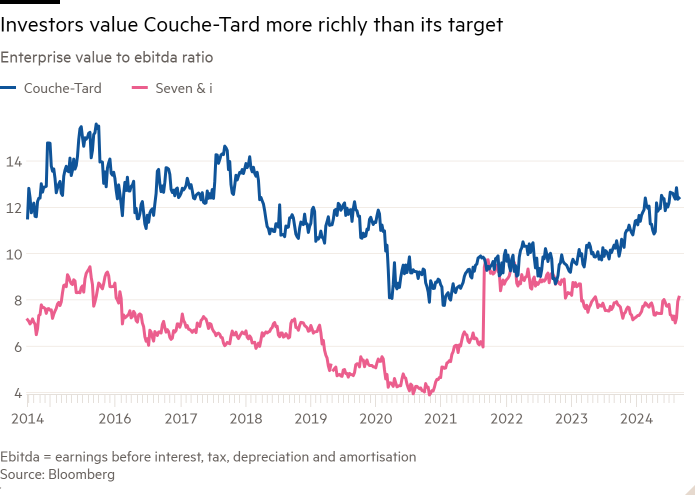

That gulf in performance has opened up a gap in both market capitalisation and valuation between Couche-Tard and Seven & i. That, along with the changing M&A guidelines and the company’s need to appear more receptive to the priorities of shareholders, has opened a rare opportunity for the Canadian group.

“What Couche-Tard is doing is taking advantage of the conglomerate discount that Seven & i has been experiencing for a long time,” says Shunsuke Kuriyama, an analyst with Jefferies in Tokyo.

“Buying the entire company is probably cheaper than just buying the international business, especially with the potential divestiture of other assets.”

It has been almost 10 years since Japan introduced its first corporate governance and stewardship codes.

During that time there have been clear signs of progress — and a degree of disappointment that the reforms have not made as much difference as originally hoped.

But the announcement of Couche-Tard’s deal has electrified Japan’s financial industry. In more than 30 interviews with bankers, lawyers, fund managers and government officials, the majority described the bid as a turning point, a catalyst or a litmus test of Japan’s willingness to embrace a version of shareholder capitalism that it has long avoided.

Herrick, at Artisan Partners, says any rejection of Couche-Tard’s bid would set an important precedent for the rest of the market. “If [Seven & i] walk away, shareholders need to understand what was on offer. We need to know, if Seven & i is saying that the offer isn’t good enough, what exactly wasn’t good enough.”

On Friday, Artisan sent a letter to the board of Seven & i setting a deadline for it to update investors on the takeover bid, warning that management will be “held accountable” if it dismissed the approach out of hand.

Many analysts and investors suspect that managements across Japan, watching this saga unfold, are growing concerned they will find themselves in a similar position before long.

Several prominent activist funds — two of which were involved in epic battles with the electronics group Toshiba — have previously said that their power to change Japan would ultimately be eclipsed if more overseas corporations and private equity funds followed Couche-Tard’s lead.

Japanese M&A lawyers say that, since Meti’s revisions to the guidelines last year, they have been inundated with requests from listed Japanese companies for advice on the options available should an unsolicited bid emerge.

Whatever happens with Couche-Tard, its takeover attempt will have profound implications for Seven & i and the rest of Japan, according to veteran fund managers. This is a market, says one, where companies have for decades managed to convince the outside world that they were simply not for sale at any price, and that an unsolicited approach would be doomed to more or less instant failure.

Many of the gems of corporate Japan, some of which have also posted mixed financial returns, or whose shares trade at notable discounts to their US or European rivals, can now reasonably expect to receive serious takeover approaches that they cannot simply dismiss, says one senior Japanese lawyer.

The head of one global fund that has invested in Japan for several decades says he had expected that the first significant tests of the new M&A guidelines would come from Japanese companies looking for domestic consolidation. He adds that this was the outcome probably intended by Meti when it updated the corporate governance regime.

But the Couche-Tard bid leapfrogs that process, bringing a foreign company in as an unsolicited bidder and potentially paving the way for many more.

Some have talked about Calbee, the snack maker, consumer products group Kao, video game developer Square Enix, sportswear brand Asics and brewer Sapporo as examples of Japanese companies that would be prized additions for larger overseas rivals.

Japan’s M&A market, the investor continues, is perfectly set up for aggressive takeover tactics. Companies are not used to running defence campaigns, reflexively seeking a friendly domestic bidder rather than standing their ground. There is no shortage of these “white knights” because so many Japanese industries are highly fragmented.

Nigel Muston, a Japan retail analyst at CLSA Securities, says investor behaviour suggests a widespread belief that a Rubicon has now been crossed.

“Even if most investors feel that [the Couche-Tard] deal is not going to happen, they are staying in Seven & i stock because they believe it can never go back to where it was before the bid was announced,” he says.

7-Eleven’s image of permanence and centrality to Japanese daily life could yet become a key factor in this particular battle, say analysts, and ensure that every twist in the tale will come under intense scrutiny.

Meti in particular will be closely watched for signals that its more progressive faction, which seems happy for Japan to become a centre of global M&A activity even if that means some famous companies falling into foreign hands, is in the ascendancy.

The target may yet find itself protected, say analysts at JPMorgan. In a country where earthquakes, tsunamis and tropical storms are relatively frequent, the government sees the nation’s convenience stores as “lifeline infrastructure” that should not be under the control of non-Japanese owners.

But Ellen Lee, a portfolio manager at Los Angeles-based Causeway Capital Management, which is a top-30 shareholder, says Seven & i’s board “should not seek government protection without merit”.

“Maximising shareholder value should be a key criterion,” she adds. “To disregard it will jeopardise global investors’ confidence in governance at Seven & i and the effectiveness of Japan’s corporate governance reforms.”

The primacy of shareholder value, largely unquestioned in other large developed markets, is still very much up for debate in Japan. Ogawa, at Nippon Active Value Fund, describes it as “the eternal question: for whom is a Japanese company run?”

There appears little doubt about the bidder’s views on the matter. Couche-Tard is “the thing that was always missing”, according to the veteran investor. “Someone to step up and accept the risk of becoming known as a horrible person, an aggressive bidder prepared to take a reputational hit in Japan. But Couche-Tard hasn’t got anything else it will ever want in Japan, so what has it got to lose?”

Travis Lundy, an independent special situations analyst who publishes on the Smartkarma platform, says the Canadian group “is very aggressive and religious about costs, while Seven & i is religious about customer experience, offering multiple kinds of delicious onigiri, freshly made sandwiches, fluffy bread, yoghurts, the lot”.

For many Japanese, that is what the takeover battle could ultimately boil down to. “If Couche-Tard’s goal is to increase margins,” says Ogawa, “it’s hard to figure out how that can happen without a degradation of customer experience.”

Additional reporting by Harriet Agnew in London