Stephen has been a client of private bank Hoare for his entire life and intends to remain one.

Sure, the UK’s oldest privately owned lender did not offer him the best mortgage. It was slow to launch its banking app and behind others in rolling out a digital card for Apple wallet. But when the 60-year-old investor, who declined to give his real name, needed help to write his will, he knew he could count on the elite lender.

“The one thing they do better than others is the sense that you can completely and utterly trust them,” he says. “The minute there’s a problem, someone you know will be on it and continue to be on it until it’s solved.”

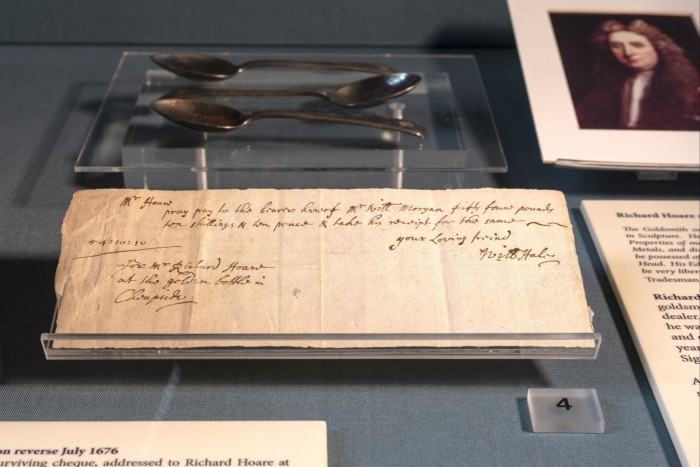

C. Hoare & Co was founded in the late 17th century to cater to blue-blooded clients, and has numbered John Dryden, Jane Austen and Lord Byron among its account holders. Its oak-panelled offices on Fleet Street are reminiscent of the golden age of privately owned merchant banks, which flourished across the City of London to fund overseas trade. In its 352 years of existence, it has been owned by 12 generations of the Hoare family.

Over time, many private banks have turned away from their roots in commercial banking to focus on personal banking and wealth management. Many, including NatWest-owned Coutts, were swallowed by bigger banks and lost their private ownership structure. Now they are trying to find their place in a digital world where customer needs and wealth are changing shape.

Stricter regulation has curtailed their often infamous reputation for discretion and tax optimisation. Meanwhile, the rise of wealth managers such as St James’s Place and investment brokers such as Hargreaves Lansdown (along with cheaper digital upstarts), has eaten into their share of the high net worth market.

Some three centuries after the oldest institutions were founded, account holders and would-be customers face a pressing question: are private banks still worth it?

Private banks are by definition discriminatory. They typically require customers to have at least £100,000 in annual income and often have minimum savings and investment thresholds that can go up to, in the case of Barclays Private Bank, £5mn.

Fees depend on clients’ individual finances, but typically range between 1 and 2 per cent of their assets. They tend to be lower in percentage terms for wealthier clients and can be scrapped for the wealthiest of them.

Unlike retail banks, private lenders offer a full suite of tailored banking services, including specialised loans, high-value mortgages and structured loans to help clients invest in less traditional assets including commercial real estate and hotels.

Camilla Stowell, Coutts’ head of client coverage, says the bank provides a broad range of wealth management services, including banking, lending and investments, and financial planning. “The ability to provide flexible and complex credit can also be important for clients looking to utilise their asset base to invest in business opportunities or purchase luxury items like art or classic cars.”

Private banks’ main selling point is their focus on client relationships, with some even offering concierge services. HSBC says its concierge service can book the best tables at a Michelin-starred restaurant for its clients on 24-hour notice and set tickets aside for upcoming events including concerts and sports tournaments.

524,464Number of accounts managed by private banks — down 1 per cent in the past year

When FT Money asked readers for their own experiences with private banks many, like Stephen, cited the better service. They tend to pair clients with dedicated bankers who can hold their hands through financial decision making. They pick up the phone, can arrange meetings at the drop of a hat, take out their clients for lunch and visit them in their homes.

Alex Barkley, a banking strategist and managing partner at Lancero Capital, a venture capital and private equity investor, says one of the key things they sell is the ephemeral feeling of belonging to an elite club. “You feel like a rock star. You feel like you’ve made it,” he says.

Andrew Salmon, chief executive at Arbuthnot Latham, a private bank founded in 1833, is keen to stress that his doors are open to clients beyond the ultra-rich.

The bank, which has a specialised division for media personalities and executives — and became a creditor to bankrupt tennis player Boris Becker — typically requires clients to have £500,000 in investible assets, deposits or borrowing needs.

“Private banking [evokes] mega yachts and sparkling seas and I’m sure it exists for the people who are in that category,” he says. “But it’s required by people who have much more modest wealth than that.”

A stellar relationship with your banker can only get you so far. Some clients told us that having a close personal relationship with their bank does not necessarily translate into accessing bespoke financing.

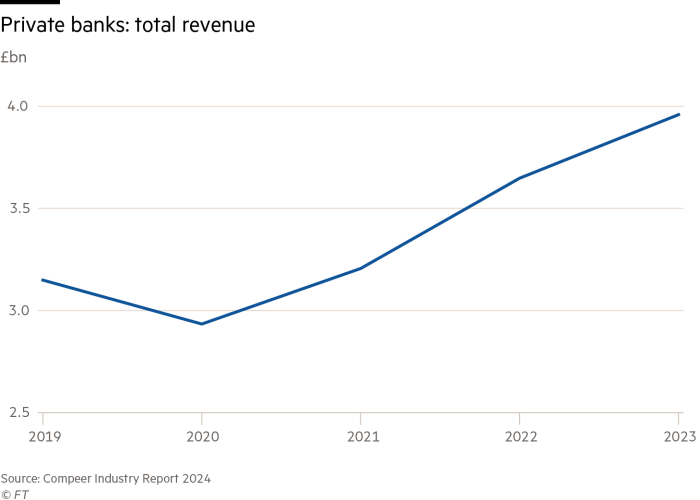

Private banks face record costs linked to the burden of regulations and the cost of modernising their legacy IT systems. A report by data company Compeer found that 24 of the UK’s private banks had a total cost base of £2.8bn last year, compared with £1.8bn for both full service wealth managers and investment managers.

Chartered financial planner Michael Lawrence says that many financial adviser platforms offer a “far cheaper and comprehensive” technology-driven service. By contrast, old technology and bank regulation had created a risk for private lenders that meant they had lost their discretionary focus for most clients.

“Private banks still offer useful services, but the level of wealth one needs to have to benefit from the higher cost has gone up considerably in the last decade,” he says.

Private banks had a combined £407bn of assets in the UK at the end of 2023 and managed about 524,000 accounts, roughly half the 1mn accounts managed by full service wealth managers. And while wealth managers increased their account numbers by 2 per cent in the past year, the number of private banks’ customer accounts fell by 1 per cent over the same period.

C Hoare & Co offloaded its wealth management arm to a subsidiary of asset manager Schroders in 2017, saying a bigger owner would help it meet technology and regulatory demands.

“Anyone coming to a private bank with £5mn of assets is either uninformed, has an ego that needs to be associated with a private bank name, or is poorly advised because they cannot actually do very much for you,” Lawrence says.

“Over the years the compliance regulations and their cost of operations mean that most people are invested via a single unit trust, or a model portfolio service, meaning [for most] there is next to no discretionary element.”

Private banks contacted by the FT declined to comment.

Charles McDowell, a luxury property agent who is also a client of Coutts, says his bank’s back office and underwriting processes are “a shambles” that no amount of delightful customer service can solve. McDowell says the bank was not able to give him the overdraft he wanted and could afford, blaming the mandatory and onerous stress-testing process.

“I have a charming bank manager who looks after me, genuinely cares about me as a customer and what have you, but I’m afraid the mechanics of the bank are wholly outdated,” he says.

Another Coutts customer said the service quality had degraded over time, with perks including access to airport lounges and luggage emergency cover becoming fee-paying. The closure of a local branch affected his ability to meet advisers, while he was turned away for a bridging loan which he could afford that the bank said NatWest could not provide.

Coutts said: “We do not comment on individuals’ circumstances, including confirming whether or not they are a client.”

Private bankers’ hands are tied by the same regulations and processes that govern other retail banks. This includes stringent anti-money laundering and compliance checks that can be time-consuming; and stress-testing for mortgage availability. Like other retail banks, they have to enforce Consumer Duty principles and will be required to reimburse fraudulent payments of up to £415,000 from October.

Some of these rules hit private banks hardest because they deal with clients whose wealth is spread across multiple tax jurisdictions and in more complex investment products.

Peter Tyler, director of personal banking at trade body UK Finance, says private banks in the UK face an increased focus on anti-money laundering controls that made private banking more challenging and costly than retail banking in the mass market.

Tom, a former investment banker, was “debanked” from his private bank once he was no longer a tax resident in the UK. Having to move 17 accounts was “quite a huge pain in the ass,” says Tom, who declined to give his real name.

“It’s a bit like Brexit in that it’s a ton of work, there’s no benefit, you don’t have a choice about whether you do it. And at the end of it, the best result is slightly worse than where you were before.”

After transferring money out of his account in chunks of £50,000 due to daily limits, he realised he could get better rates on foreign exchange with fintech Wise. But those transactions were flagged as suspected fraud, leading to him having calls with the bank that each cost money in addition to costs linked to the tax implications of moving the money elsewhere.

“You can have worse divorces than this. They were with me all the way through university, through my career as a banker, my development, career changes.”

Another existential challenge for private banks is appealing to a new generation of wealth creators who do not share the same characteristics as their historic aristocratic client base. The lenders who can appear traditional and stuffy are courting dynamic clients such as tech entrepreneurs, athletes and musicians.

“Do tech founders and entrepreneurs find a 200-year-old bank sexy and exciting? Probably not,” says Barkley.

They also come with baggage. Many of those banks flourished due to their role in facilitating international trade through the British empire, which has also come under more scrutiny in recent years and can repel certain clients.

Arbuthnot Latham founders, Alfred Latham and James Alves Arbuthnot, were both linked to the slave trade, and the bank would go on to be a funder of Britain’s colonial exploits. In 2020, the bank told The Guardian newspaper: “Arbuthnot Latham stands against racism and discrimination in all forms, and is committed to diversity across the bank.”

Stowell at Coutts says the 330-year-old bank, which counts the UK royal family among its clients, was looking to “make sure that [it doesn’t] live in the past” and focused on being digital, including replicating some of fintechs’ “fabulous ideas”.

Managing it in practice appears to be a balancing act the bank is still trying to navigate. In an email to staff in June seen by the FT, Stowell told off bankers for “turning up to these visible meetings in T-shirts etc” and “losing the impact of the experience that we want to deliver”.

The bank reminded client-facing staff to blur their Zoom background and “dress for discretion not distraction”.

Banks have in recent years tried to embrace more modern values. Coutts has been a certified “B-corp” since 2019, meaning it meets a set of standards linked to “social and environmental performance, public transparency and accountability to balance profit and purpose.”

The bank also boasts inclusion credentials that include “providing feedback to leaders on how their teams are feeling” and “creating a great place to work that celebrates diversity”.

Such a rebrand is not easy to pull off. Coutts was rocked by a scandal last year after politician Nigel Farage claimed he had been “debanked” by the lender for his political views.

Although an independent review found his “debanking” was primarily linked to commercial factors, the politician proved that the bank’s reputational committee had accused him of being a “disingenuous grifter” whose values clashed with those of Coutts as an inclusive organisation.

The bank was then told to improve its communications to clients by the law firm that conducted an independent review into the affair.

McDowell, who has been a customer for most of his life, says the bank should “stop doing all that B-corp stuff and all that nonsense of responsibility, accountability and trying to be a moralistic organisation” and “concentrate on just offering people a proper banking service”.

“I couldn’t give a damn what they think about social morality and the worst of it,” says McDowell. “All I want is for them to be a bank”