Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

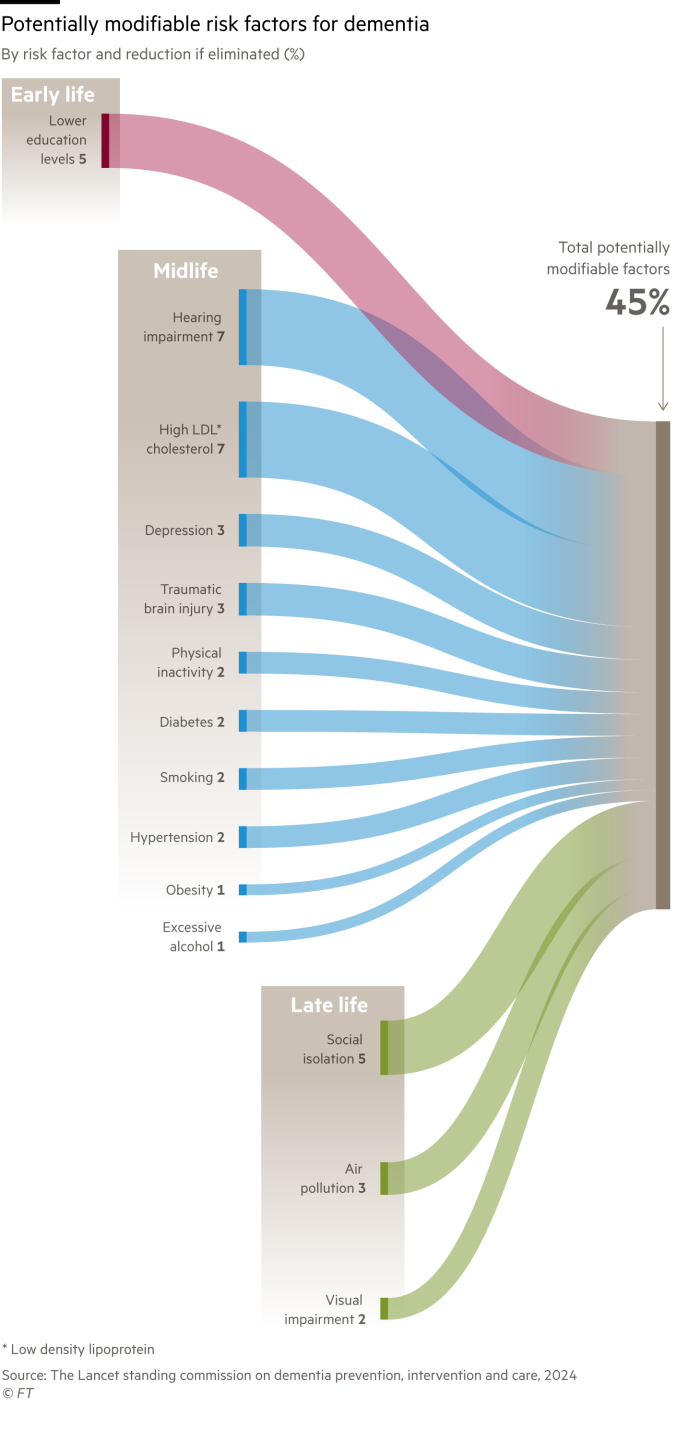

Scientists have for the first time linked high cholesterol and vision loss to the development of dementia, including them among 14 critical risk factors that if reduced can prevent or delay nearly half of cases.

High cholesterol in the over-40s and hearing impairments were most commonly associated with people developing dementia globally, according to new research by The Lancet Commission on dementia prevention, intervention and care.

Lower education levels in early life and social isolation in later life also played an important role, the report said.

Geir Selbæk, a member of the commission and research director at the Norwegian National Centre for Ageing and Health, said the research had for the first time demonstrated a causal link between addressing the “modifiable” risk factors and reducing the likelihood of developing dementia by up to 45 per cent.

“Stopping smoking actually decreases risk, treating vision loss decreases the risk. So that is a major thing,” he added.

The commission called for individuals to take action on the several risks linked to lifestyle choices and for governments to create measures to reduce risk factors at a population level, as cases of dementia reach record highs globally.

Susan Kohlhaas, executive director of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK, said many of the risk factors were “things individuals can do something about, such as smoking”.

But other issues, such as air pollution and early childhood education, were “bigger than individuals and communities”, she added. “Tackling them will need structural changes to society to give everyone the best chance of a healthy life, free from the impact of dementia.”

The risk-reduction impact would be across populations, rather than guaranteeing that any individual will avoid dementia, according to the report.

But Selbæk said another striking lesson to emerge from the research was that “there’s a lot that you can do to decrease your dementia risk . . . in terms of physical activity, probably mental activity and so on . . . even when you are 80-plus”.

The number of people living with dementia globally is expected to almost triple by 2050, with health and social costs related to the condition estimated to be more than $1tn a year.

But some high-income countries, including the US and UK, are seeing reductions in the proportion of older people with dementia, the report found, attributing the fall in part to “building cognitive and physical resilience over the life course and less vascular damage”.

However, the commission warned that a specific focus on low- and middle-income countries was needed, as they were likely to be less well placed to address the risk factors for their populations.

Selbæk said drugs that can ameliorate some symptoms of dementia and cataract treatment to counteract vision loss were “not easily affordable [or] accessible in low and middle-income countries”.

Report co-author Cleusa Ferri, a professor and epidemiologist based in Brazil, also warned of the “much higher burden of dementia risk factors in low- and middle-income countries”, given the expected rise in dementia over the next few decades related to the population ageing rapidly and rates of high blood pressure, diabetes and obesity increasing.

“We need urgent policy-based preventive approaches that will have huge potential benefits far in excess of the costs,” she added.

An array of steps should be taken to reduce risk factors, the report said. This included preventing and treating hearing loss, vision loss and depression; promoting being cognitively active throughout life; reducing vascular risk factors such as obesity; improving air quality; and providing community environments that will increase social interaction.

A separate piece of analysis published in the The Lancet Healthy Longevity journal suggested that, using England as an example, savings of more than £4bn and over 70,000 extra “quality-adjusted life-years” could be generated over roughly 20 years if some of these steps were taken.

Illustration by Ian Bott