There is a lot to be said for being a lazy investor. Once you have decided to adopt a passive strategy, it is easy to set up a direct debit into a global tracker fund (within your tax wrapper of choice, of course), then sit back and wait for your low-fee investments to compound away.

Drip feeding money into the stock market at regular intervals, there’s none of the stress of trying to time the market, or wasting time searching for stock picking ideas that could prove to be ten-baggers. Nor will you waste money on frequent trading fees, or pay handsomely for an active fund manager to pick stocks on your behalf.

The lazy route to investment success has certainly paid off — for now.

Over the past 12 years, retail investors in the UK and Europe who favour passive funds have saved some £80bn in fees compared with similar active fund picks (according to Vanguard, which just happens to be the world’s biggest passive fund house).

However, it’s the relative investment performance of cheaper passives against their more expensive active counterparts that is turning more investors on to the lazy route to riches. In recent years, the growing dominance of the Magnificent Seven tech-focused stocks has powered passive US funds and global trackers to new and giddy heights.

Astonishingly, only 35 per cent of actively managed funds have outperformed the average passive fund in their sector this year and stretching back over the past decade, according to stockbroker AJ Bell’s latest Manager versus Machine report. Or, to put it another way, nearly two-thirds of actively managed funds have been charging investors over the odds for a lacklustre performance.

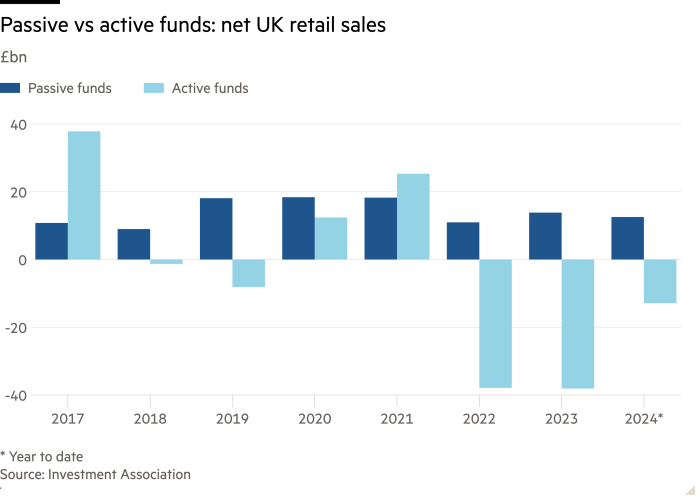

No surprises, then, that investors continue to dump active funds and pump their money into passives [as AJ Bell’s analysis of Investment Association data clearly shows].

UK retail investors have withdrawn a staggering £89bn from active funds since the start of 2022 on a net basis, investing £37bn into trackers (higher interest rates on cash and growing pressure to spend money held in investments help to explain the gap).

“Nevertheless, these are unprecedented outflows,” says Laith Khalaf, head of investment analysis at AJ Bell, adding: “Active managers must be starting to feel like an endangered species.”

Passives have been a win-win for lazy investors in terms of fees and performance, but here are three areas where it pays to take a more energetic look at your portfolio.

Top of the list? Older pension investments you may be sitting on. For the first time, AJ Bell has crunched data on active funds held within workplace and private stakeholder pensions which are managed by big insurance companies (including but not limited to Aviva, Scottish Widows, Phoenix and Legal & General).

Here, the rate of active underperformance was even greater than the wider market: just 24 per cent of active pension fund choices had beaten the average passive fund equivalent over the past ten years, dropping to 9 per cent in the global fund sector. Yes, you read that right — 91 per cent of investors in these products could be better off, if only they checked their pensions paperwork and switched.

Nor are these small funds. Although AJ Bell stopped short of naming and shaming the worst offenders, such funds collectively hold hundreds of billions of pounds worth of retail investments, and their performance will dictate the retirement prospects of millions of British people.

Khalaf says that older, legacy pensions are more likely to contain active funds run by insurance companies, or others run by external managers that it was possible to purchase within their plans. He thinks high charges for older products and widespread “closet tracking” are partly responsible for the lacklustre performance. So do your old pensions contain any?

With legacy company pensions, it’s possible the “default fund” option may contain exposure to some active fund components — especially if your investments were built up prior to 2012 (after this point, Khalaf says auto-enrolment prompted many scheme managers to overhaul their default funds). Within old stakeholder plans, it’s more likely active funds will have been selected by the pension holder at some point — though they may not have been reviewed for decades.

“Finding out precisely what your legacy pensions are invested in is a challenge, but it’s well worth contacting providers and asking them for the name of funds you’re invested in, the investment objectives of that fund, and the charges,” he says.

Second, passive investing still requires some active decisions to be made — namely the indices you choose to track, and the fees on the ones you select. Over the past 10 years, the difference between £10,000 invested in the most expensive FTSE 100 tracker (with an annual fee of 1.06 per cent) versus the cheapest (0.06 per cent) was £1,540.

Finally, passive investors need to be aware of the growing concentration risk they’re exposed to. Thirty per cent of the S&P 500’s total weighting is made up of those “magnificent” seven stocks: Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Nvidia, Alphabet, Meta and Tesla.

Even diversifying into a global tracker will only dilute this risk somewhat — the S&P 500 accounts for about 70 per cent of most global indices. This has paid off for the lazy investor in recent years — but what if future performance is less magnificent? With so much riding on expectations of future growth, any wobble in earnings could prove volatile.

One reason many active fund managers have underperformed is because they have trimmed holdings in the tech giants to ensure they don’t have more than a certain percentage of their assets in a single stock.

AJ Bell calculates that just to match a passive fund’s exposure, an active US equity fund would now need to hold over 7 per cent in Microsoft and 6.6 per cent in both Apple and Nvidia. These are pretty punchy positions for an asset manager to adopt — and even if they dared, they still wouldn’t beat the market.

Away from the Magnificent Seven dominance in US and global indices, there are many other areas of the stock market where active managers are more likely — though not guaranteed — to add value.

Geographically, 52 per cent of active fund managers targeting the Asia Pacific region (ex-Japan) have outperformed their nearest passive benchmark over the past 10 years, AJ Bell’s study found. For global emerging markets funds, it’s 53 per cent.

Other areas where active managers have a higher chance of outperforming include funds targeting smaller companies, income stocks and even corporate bond funds.

So if you did want to diversify and add exposure to specialist areas of the market you think will outperform, you could add some small, satellite fund picks (be they active or passive) around a largely passive core portfolio.

But in doing so, you will be moving away from the classic “set and forget” model of passive investing so beloved of the lazy investor. You will need to manage your portfolio much more actively, regularly reviewing the performance of your investment choices and rebalancing your strategy as needed.

Whatever route you choose, let this research be a reminder that financial inertia surrounding fund choices and fee levels is a strategy that will make the fund managers richer — not you.

Claer Barrett is the FT’s consumer editor; [email protected]; X @Claerb; Instagram @Claerb