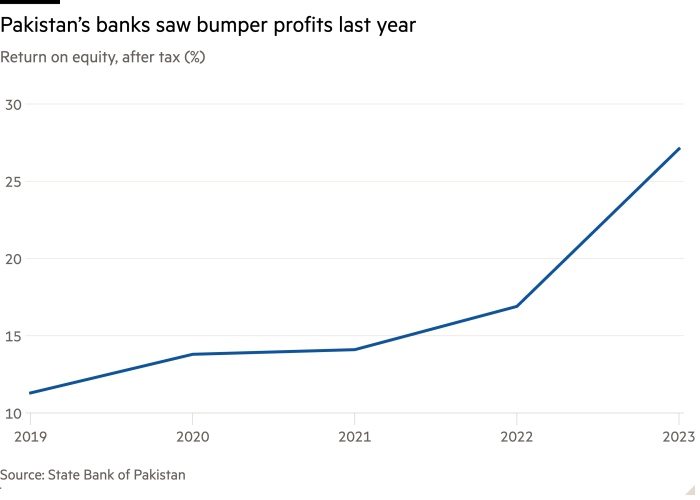

Pakistan’s banks have enjoyed bumper profits and some of the highest returns in Asia in recent months, as two years of sky-high interest rates have driven a boom in earnings from the government debt that dominates their balance sheets.

Seven of the 15 banks with the highest second-quarter total returns in the Asia-Pacific region are in Pakistan, including Standard Chartered Pakistan and Bank Alfalah, according to S&P Global. After-tax profit in the entire banking sector almost doubled to Rs642.2bn ($2.3bn) in 2023, according to the State Bank of Pakistan. During the same year, the economy of the world’s fifth most populous country contracted amid one of Asia’s worst recent economic crises.

The past two years, during which the SBP jacked up interest rates to about 20 per cent to curb inflation that reached as high as 38 per cent in June 2023, had been “party time for the banks”, said Mohammed Sohail, chief executive of Topline Securities, a brokerage.

“Bankers and their shareholders were the happiest people in Pakistan in this most recent economic crisis and rate cycle,” he said.

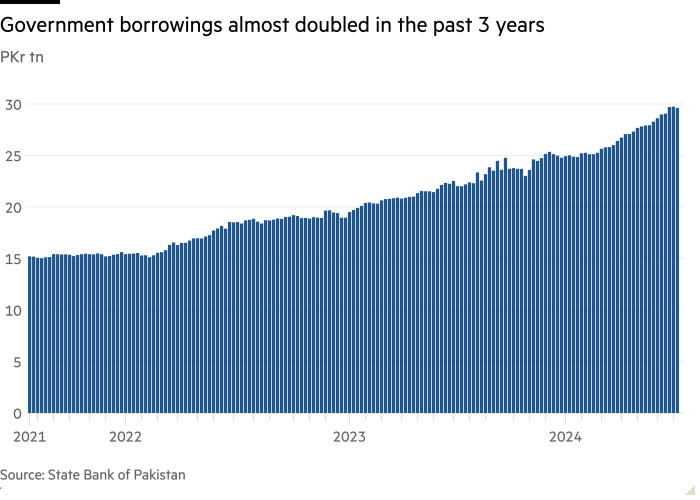

Pakistan faces an ever-expanding debt burden, with a total debt-to-GDP ratio above 74 per cent. Its domestic debt, which is largely held by the commercial banks that line I I Chundrigar Road, Karachi’s Wall Street, has ballooned to more than Rs43tn as of March 2024, almost half of GDP and up from Rs11tn a decade ago.

Government borrowings for budgetary support reached Rs29tn at the end of June, almost double the Rs15tn borrowed three years earlier. The Karachi-based central bank has pumped money into lenders to guarantee enough liquidity to finance the government’s widening debt burden.

Amid Pakistan’s regular booms and busts, government paper has remained a liquid and risk-free path to net interest income for the banks, especially during the most recent downturn. Banks’ sovereign exposure has risen to more than 54 per cent of total assets, roughly triple the average for emerging-market economies, according to data compiled by Fitch Ratings.

“Where there was an opportunity for higher returns, they were capitalised on,” said Rehmat Hasnie, chief executive of the National Bank of Pakistan, one of the largest banks in the country. “It’s basic economics.”

“When you have these difficult times, you know interest rates go up and they will basically compensate for a depreciating currency,” said Mattias Martinsson, chief investment officer of Stockholm-based Tundra Fonder, which has a $200mn frontier markets fund, with Pakistan its second-biggest weighting after Vietnam.

The financial sector has powered a historic stock market boom in Pakistan, even as the economy as a whole remains in the doldrums.

Investments, which are about 56 per cent of total assets across the banking sector, increased by Rs7tn in 2023 — a more than 40 per cent rise from the previous year — with 98 per cent of the expansion coming from purchasing government securities, according to data from the SBP.

In the decade to 2021, the banking sector had a compound annual growth rate of 9 per cent, according to Sana Tawfik, an analyst at Arif Habib Limited, a brokerage. This has surged to 45 per cent in the past two years.

But the risk of a default, and a resulting restructuring of domestic debt, is looming, as Pakistan navigates mounting debts that have sent it to the IMF nearly two dozen times since its first loan in 1958. The crisis-hit country teetered on the brink of default in June 2023 before the Washington-based lender delivered a last-minute emergency bailout. Pakistan secured another three-year, $7bn IMF loan deal this month.

Pakistan’s government is also clawing back a chunk of bank profits through higher taxation, with income tax expenses as a percentage of profit before tax hovering close to 50 per cent last year, according to the SBP report. The banking sector paid Rs618bn in income taxes in 2023, almost double the amount they paid the year before, according to data from the Pakistan Banks’ Association, a Karachi-based industry group.

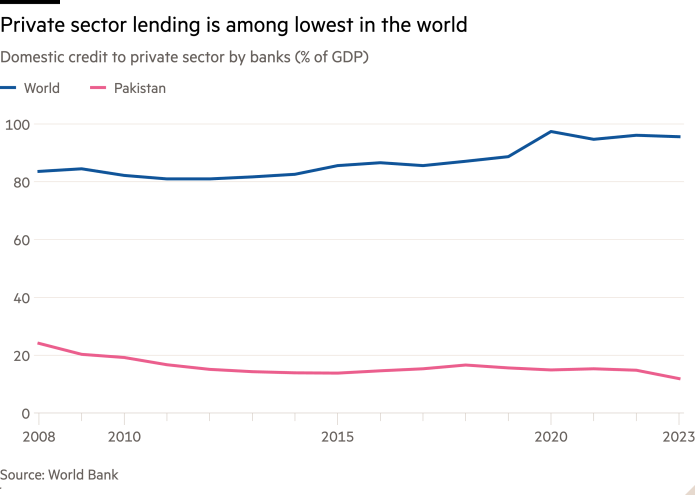

The flipside of high exposure to the government is that banks have comparatively little left to lend to the private sector. At its latest meeting, the central bank’s monetary policy committee expressed concerns about “increasing reliance on banks for deficit financing, which has been squeezing borrowing space for the private sector”.

Pakistan has one of the lowest rates of domestic credit to the private sector as a percentage of GDP. It was just under 12 per cent in 2023, down from 24 per cent in 2008, according to the World Bank.

“Economic conditions [in Pakistan] have seldom encouraged businesses to take loans, and banks are afraid of non-performing loans,” said Tawfik of Arif Habib. “When they can get better returns on risk-free investments, there is little incentive for them to take on the risk of lending” to the private sector.

Bankers claim that the profits from the past two years will give them the cushion needed to bet on Pakistan’s riskier small and medium-sized enterprises. “Higher profits have enabled us to strengthen our capital base and thus have a higher risk absorption capacity going forward for lending to the private sector,” said Hasnie.

Pakistan, with a largely informal and unbanked economy, weak legal protections and seesawing state policies, is likely to remain a tricky place to lend, bankers and analysts say. “We will not see an explosion of private credit supply [when rates come down],” said Hasnie.

Additional reporting by Chris Kay in Mumbai