Lex Greensill had an uncanny ability to draw esteemed people and institutions into his orbit, before tarnishing their reputations through association with his dubious financing schemes.

SoftBank, Credit Suisse (RIP) and Lord David Cameron all got sucked in and spat out by the respectability vortex surrounding the Australian financier (though none of them, to be fair to Greensill, are strangers to an own goal elsewhere).

But Greensill — who has been dabbling in coconut-related VC investment since his eponymous financing firm Greensill Capital imploded three years ago — is still a man who seems to care deeply about his own public image.

That, presumably, is why the disgraced financier incurred over £63,000 in legal costs trying to prevent the Financial Times from obtaining a document outlining why the UK’s Insolvency Service is seeking to disqualify him from acting as a company director.

Thankfully, the FT prevailed at the High Court in London, winning access to a key portion of the document that summarised the basis of the Insolvency Service’s action. The judge at the same time restricted release of the rest of the 300-page filing (essentially an extended witness statement) and over 8,000 pages of attached evidence.

We thought FT Alphaville readers may be interested in reading the extract from the document we received earlier this week in full. It consists of 20 pages of a sworn statement from a member of the Insolvency Service, which was originally made in March with some slight corrections made later. You can read the document below, or download it here:

Asked for comment after the court agreed to release this extract from the IS’s filing, Greensill’s spokesperson said on Tuesday:

Mr Greensill rejects these allegations, which are wholly without merit and will be robustly addressed in due course.

They also noted that Greensill has sued the UK’s Department for Business and Trade for alleged misuse of private information “during the investigation that led to this action”. The business department sponsors the Insolvency Service and is the formal claimant in the disqualification proceedings.

The fact the FT even had to go to court to fight for this was arguably a little strange.

The extract of the document contains the grounds of the government department’s action seeking Greensill’s disqualification, in essence a written statement of the core allegations from a claimant in an English court case.

In other types of proceedings, the grounds of a filed court claim are typically easily obtainable after service has been acknowledged (usually for the princely sum of £11). The document was also listed as being available for order on HM Courts and Tribunals’ public e-filing service (for our US readers: this is like a pricier and less comprehensive version of the Pacer system).

However, when the FT tried to order the document in March, paying £33, we were blocked from receiving it — instead receiving only a bare bones “claim form” containing little detail. It did, however, state that “the grounds upon which the claimant seeks a disqualification order” were laid out in the so-called Affirmation (a sworn statement) that we had been blocked from obtaining.

After the FT applied to the high court for the document in April, it emerged that some lawyers not involved in the disqualification proceedings had ordered the document through the e-filing service and (in contrast to the FT) received the document in full without issue. This was said to have been an error, but it was an extremely frustrating discrepancy.

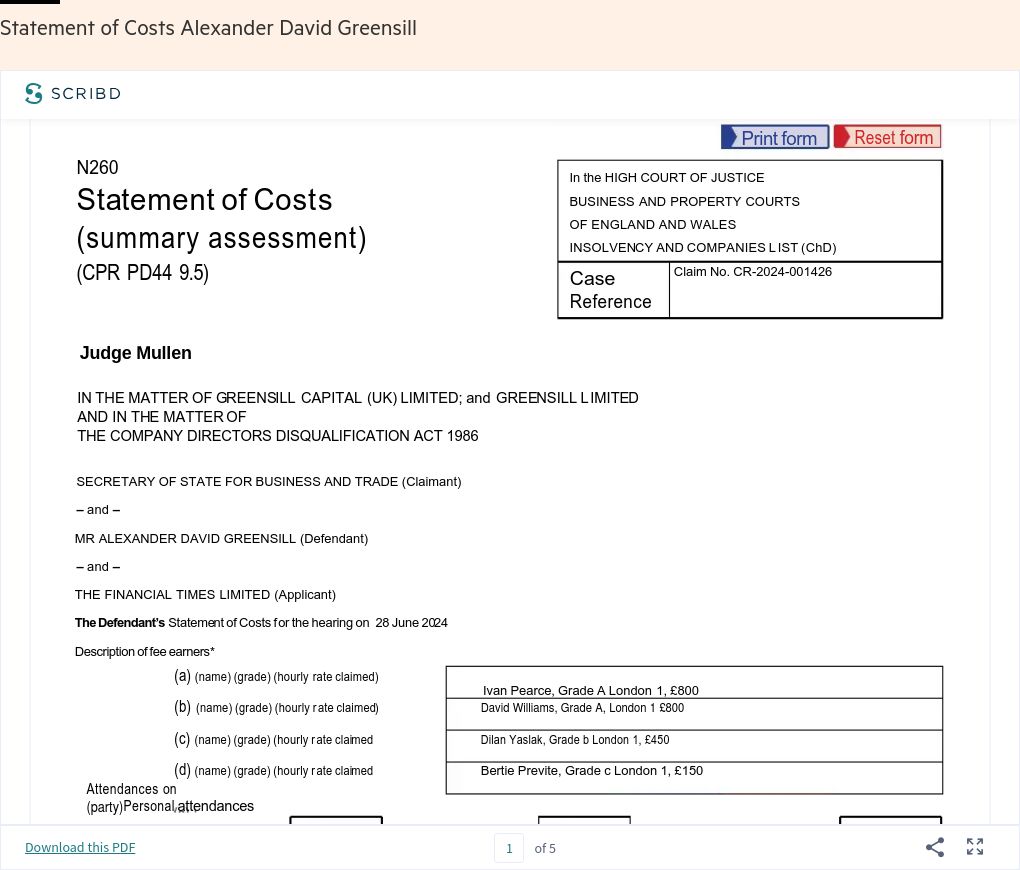

Greensill’s counsel argued that the FT’s application would allow the reporting of one side’s case prematurely before a response had been filed or evidence considered for trial. The financier also took the arguably aggressive position of trying to stick us with his legal costs. All £63,182.70 of them.

Judge Mark Mullen ordered in June that the FT would receive the key part of the document it sought, and another hearing was held on Tuesday on the issue of costs.

At the hearing, Greensill’s barrister Gavin Millar KC argued that the FT should be liable for the bill because it had made a “very wide application” that had not been successful (in effect, because the FT did not obtain hundreds of pages of sworn testimony and the thousands of pages of exhibits, nor get a restrictive Consent Order lifted).

He contended the FT had unsuccessfully applied for early access to the equivalent of a witness statement and its exhibits which, under standard court rules, would not normally be publicly accessible until trial.

However, Judge Mark Mullen said the outcome of the open justice application had been an “effective score draw”.

He added that if Greensill had “engaged in a more constructive way with the Financial Times”, rather than adopting a “wholesale objection” to the document’s release, it was “very likely” the FT’s application would not have required a hearing. As such, he rejected Greensill’s attempts to get the FT to cover his substantial legal bill.

We should add that the FT still bore its own costs for instructing solicitors and barristers. Fighting for open justice ain’t cheap.

So, to give readers a sense of how it’s possible to rack up an over-£60,000 legal bill trying to prevent reporters getting access to serious allegations of misconduct, we also thought it would be useful to publish Lex, or rather, Mr Alexander David Greensill’s statement of costs (download link here):

Millar is one of the UK’s most prominent barristers for media-related cases. Eagle-eyed readers will have spotted that his wise counsel and efforts at judge persuasion appear to have cost Greensill over £21,000.

With all that expensive advice at his disposal, we wonder whether Greensill was also given a steer about the power and perils of the Streisand effect.

If Lex Greensill has any issues settling the bill, FTAV knows of an exciting fintech firm that once promised it was “making finance fairer” through the magic of invoice factoring.

Unfortunately, however, it went bust three years ago.