The UK armed forces “cannot defend the British homelands properly” and are unprepared for “conflict of any scale”, according to the senior defence official who was charged with gauging Britain’s military strength.

Rob Johnson — who recently stood down as director of the Ministry of Defence’s office of net assessment and challenge — said the UK military was operating with a “bare minimum” that only just allowed it to mount peacekeeping and humanitarian relief operations, civilian evacuation from warzones, and some anti-sabotage activities.

“In any larger-scale operation, we would run out of ammunition rapidly . . . Our defences are too thin, and we are not prepared to fight and win an armed conflict of any scale,” Johnson told the Financial Times. “The UK has reached a situation where it cannot defend the British homelands properly.”

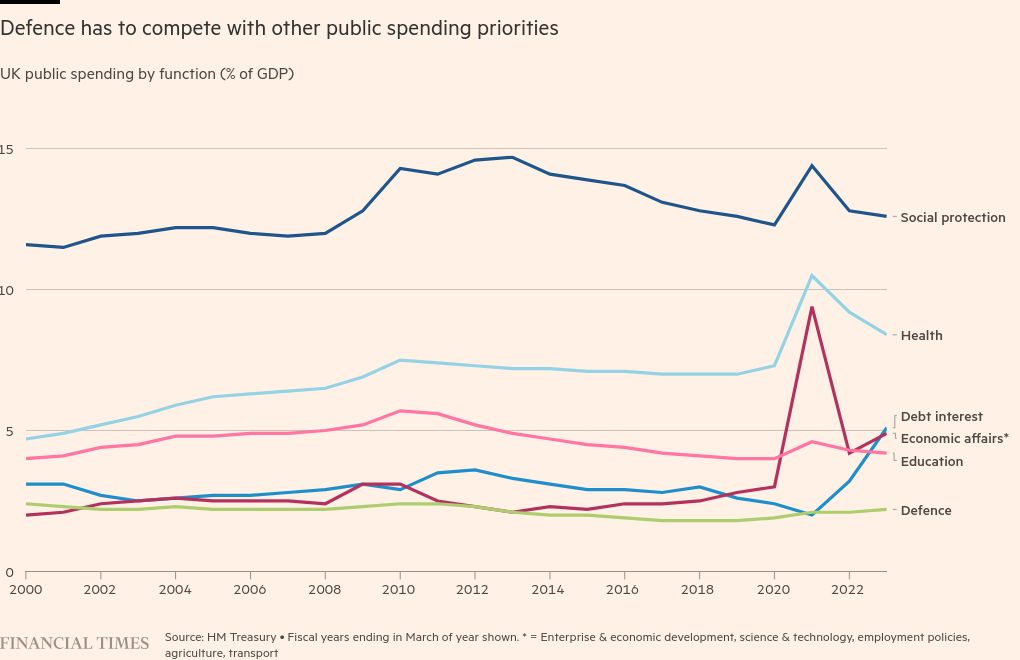

His comments come as both the Conservatives and Labour are under pressure to demonstrate their commitment to defence ahead of the July 4 general election, weighing the demands of rising global threats against straitened public finances.

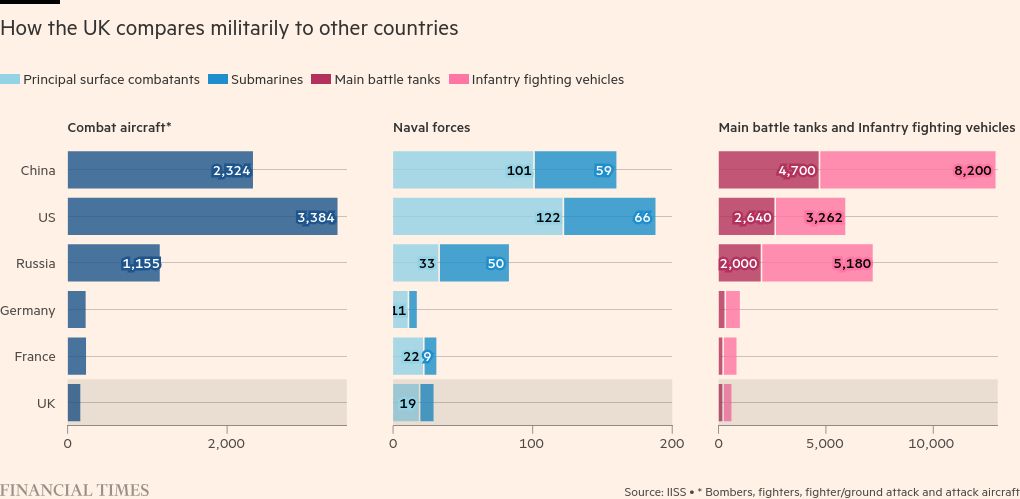

Johnson said British air defences were “insufficient” to stop long-range missile strikes, the Royal Navy lacked enough ships to patrol the north Atlantic to monitor and deter Russian submarine activity, and the Royal Air Force needed almost twice as many fighter jets as it has now.

As for mounting an expeditionary force comparable to those deployed in the Falklands or Iraq wars, British forces “would be under-equipped, leaving troops at risk”, Johnson said.

Johnson, a respected academic who previously headed Oxford university’s Changing Character of War Centre, led the MoD’s assessment office since its creation in 2022 for a full two-year term that ended in May.

His unit — based on a similar office in the US Department of Defense that has been in operation for more than 50 years — was set up as a sounding board for military chiefs to help prevent “groupthink”.

Johnson said he did not want to be alarmist but simply realistic about the scenarios that his department had war-gamed. He said he decided to issue a public warning because he was “deeply worried” about the extra investment the British military needed, particularly to counter the threat from Russia.

“The government is not taking the public into its confidence about the scale of the threat because it knows it’s not ready,” Johnson said. There was no security risk in being honest because “the Russians already know this anyway”, he added.

His bleak prognosis adds to a chorus of recent warnings by current or recently retired senior UK defence officials, who have said that Britain’s military needs to modernise given the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, and the potential for conflict in the Indo-Pacific.

Johnson indicated that the UK military was unable to fulfil the global role the government set out for it in last year’s integrated review of foreign policy, let alone fight a major adversary. “We have to cut our coat to fit our cloth,” he said.

General Sir Patrick Sanders, the outgoing army chief, said in a valedictory message to troops this month that “the urgency and imperative for modernisation is ever more acute”.

Retired Air Marshal Edward Stringer, who was a driving force behind the creation of the assessment office within the MoD, told the FT that Britain had “a shopfront military, one that can excel on displays and exercises”, adding: “But when you go behind the facade, there’s precious little on the shelves and no production line behind it.”

Stringer said that while he agreed with Johnson’s core analysis, the MoD also needed to make sure that “any extra money put in is better spent”.

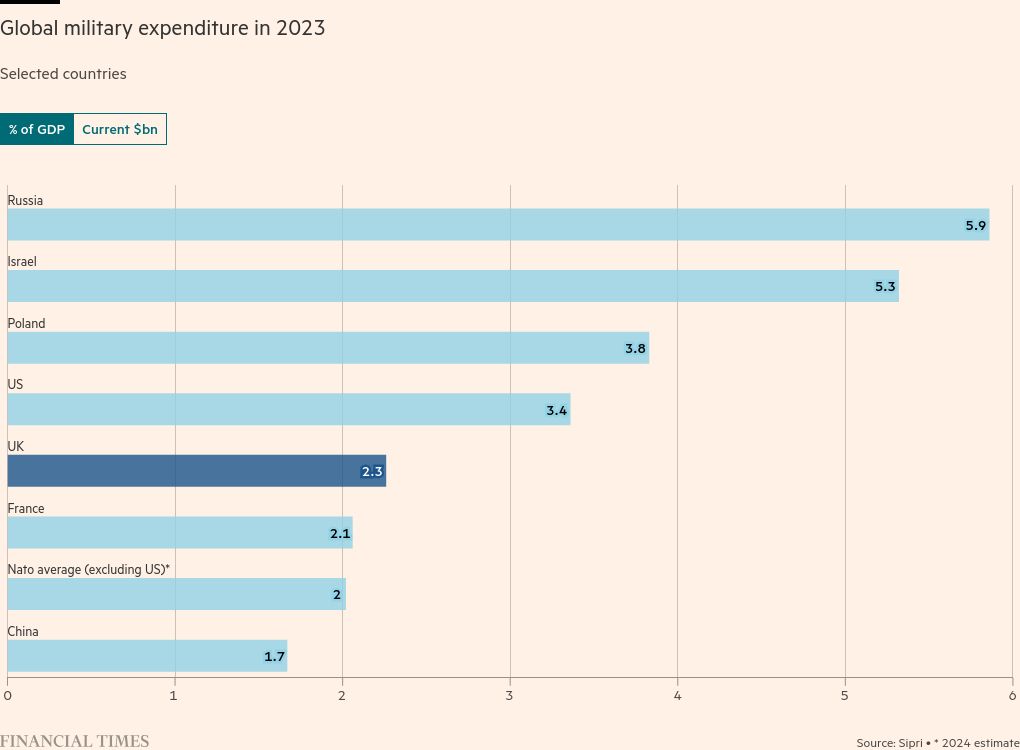

Johnson said the next government should aim to boost defence spending to 3 per cent of gross domestic product at “a minimum”. That level, equivalent to almost £80bn a year, would put UK spending on a par with the US, Poland and the Baltic states. The spending would allow the UK to modernise its nuclear deterrent and have a military “armed and equipped for the conflicts of the 21st century”, he said.

Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has pledged to boost spending to 2.5 per cent of GDP, or £66bn a year, by 2030 from around 2.3 per cent, or £54bn, now. Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer has said if his party wins the election he would also lift spending to 2.5 per cent, though he has not set a target date.

Johnson said the RAF should be prioritised and equipped with 265 combat aircraft, compared with the 137 Typhoon and the less than three dozen F-35 fighter jets it has now.

Next in line, the Royal Navy needed 25 modern warships, he said — compared with its current two aircraft carriers, six destroyers and 11 frigates. The army should, meanwhile, be expanded to 125,000 highly connected troops, from its current 72,500-strong force, and equipped with “masses of long-range artillery and long-range fires” including drones.

The scenarios his unit had assessed ranged from “almost certain” peacekeeping operations, through to “highly unlikely” nuclear war, according to Johnson. They also included sabotage, cyber attacks and other so-called grey-zone operations that Russia was already carrying out against the UK, which Johnson described as taking place “a hairline below the threshold of war”.

He said it was “highly likely” there could be a future attack on a Scottish fishing trawler, or that Russia might damage a North Sea oil rig. “Would the government consider that an act of war?” he asked. “In most cases where critical infrastructure has been attacked, the answer is yes.”

Less likely but possible could be a Russian attack on a Nato ally, such as Estonia or Poland, or a strike on a Royal Navy vessel, he added.

“The UK needs to lay out clearly what it is going to do if this happens — because being clear about the response is in itself a deterrent,” Johnson said. “Either we pretend none of this is going to happen, or we prepare.”

Military chiefs have struggled with how to reassure the public while simultaneously readying for a more perilous world.

Admiral Sir Tony Radakin, chief of the defence staff, the professional head of the UK’s armed forces, tried to find that balance in a recent speech in which he stressed that “Britain is safe” but added “that doesn’t mean that we couldn’t face attacks”.

But General Sir Richard Barrons, a former armed forces chief, said the UK military had reached the bottom of a trajectory which began with the end of the cold war. “Right now, our armed forces are not up to the job. We need to accelerate their modernisation and transformation,” he said.

The MoD said Britain’s military “stands ready to defend the UK, including with Nato allies”.

“We have fast-jets on 24-hour readiness, a deployable army on land, and a nuclear deterrent at sea,” a spokesperson added. “We train regularly to ensure we are prepared for any event, such as large-scale operations, and we continue to meet all operational commitments.”