Ed Mansel Lewis, one of England’s leading vineyard agents, is learning French.

The head of viticulture for Knight Frank has experienced a surge in inquiries from international wine producers, including Champagne houses, and thinks knowing the lingua franca might be good for business. “I see my French tutor twice a week. We’ve been doing vineyard acquisition role-plays,” he laughs.

The rapidly warming climate has made England’s southern counties fertile territory for winemaking — and hunting ground for overseas producers looking to de-risk as extreme weather and disease batter their vineyards further south.

This week, winemaker Chapel Down signalled it was considering a sale to fund its new vineyards and winery, news that boosted the company’s share price by 10 per cent. A potential acquisition of England’s biggest producer, which is currently trading at a market capitalisation of £125mn on London’s Alternative Investment Market, is the latest sign that England’s wine industry is transitioning from its humble roots to a maturing sector.

“There’s an emerging market of consolidation opportunities,” says Lewis, who has identified land in England for major producers including Chapel Down, Taittinger and Nyetimber. “It was once about buying bare land and developing it. Now it’s about M&A.”

Once the butt of jokes, the perception of English wine has been altered by the emergence of award-winning sparkling wines such as Gusbourne, Nyetimber and Hambledon, which have prompted comparisons to Champagne — and the interest of Champagne houses.

Taittinger was the first to set foot on English soil with the purchase of a Kent fruit farm in 2015, while Vranken-Pommery Monopole partnered with Hampshire winery Hattingley and is now building its own winery in Winchester. Rumours have swirled for years that LVMH’s Moët & Chandon has considered a similar move.

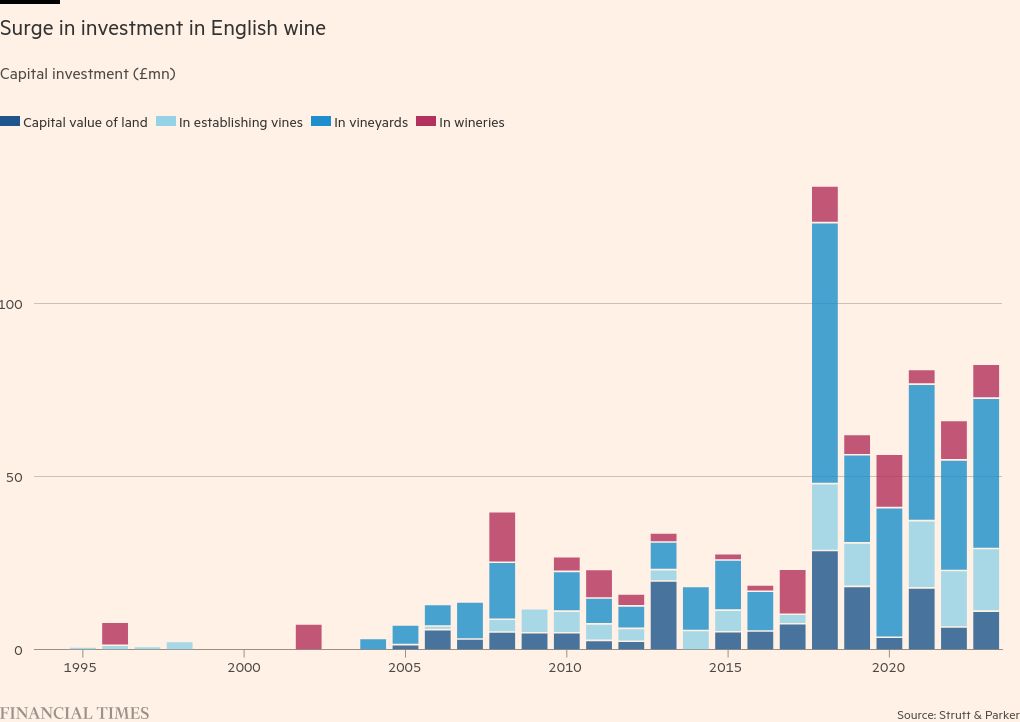

Meanwhile, Spanish cava giant Henkell Freixenet in 2022 acquired Bolney Wine Estate, and California-based still wine group Jackson Family Wines (JFW) last year bought 65 hectares of land in Essex’s Crouch Valley to plant Chardonnay and Pinot Noir for new still and sparkling wines. Investment in English wine has surged from £20mn in 2017 to £80mn in 2023, according to property consultancy Strutt & Parker.

“Over the last 15 years the industry has exploded with this realisation you can make exceptional world class wines on these shores,” says winemaker Charlie Holland, who has been tasked with launching JFW’s English venture and was until earlier this year chief executive of Gusbourne.

The English success has come at the expense of other winemaking regions. Volatile weather and warming temperatures, and the subsequent proliferation of fungal diseases, have devastated vineyards around the world, leading to a 9.6 per cent drop in global wine production in 2023 year on year, according to the International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV).

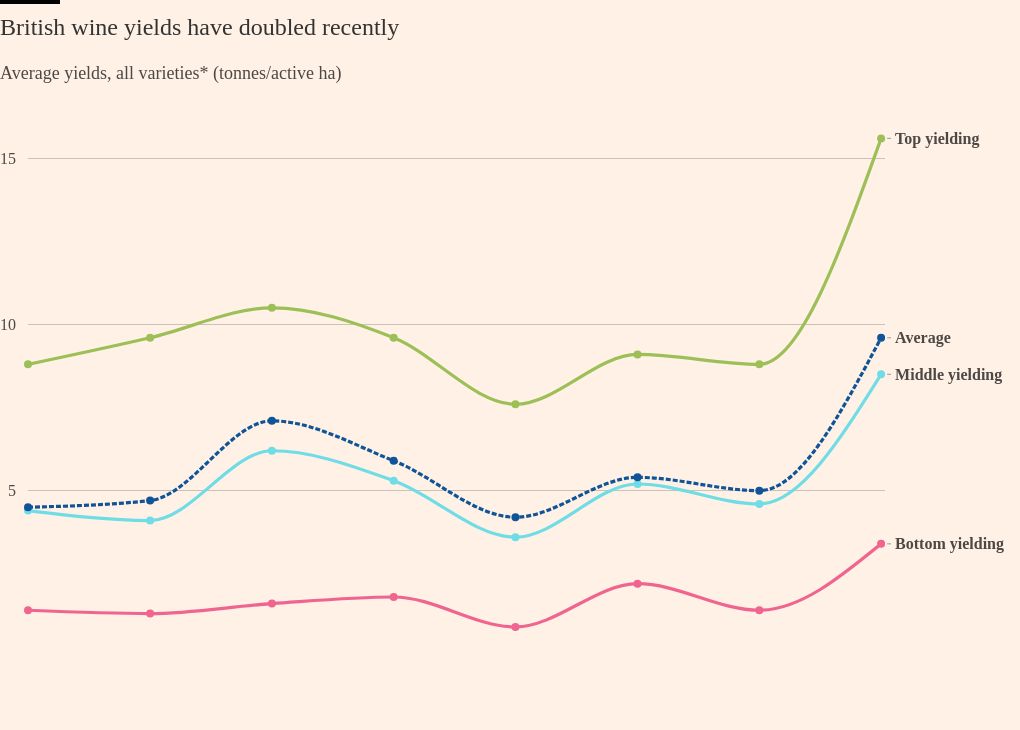

And yet England bucked the trend, last year recording its best year yet at 22mn bottles, compared to 13mn during its last record year, 2018.

“All viticulture is moving north in Europe,” says Patrick McGrath, chief executive of premium wine distributor Hatch Mansfield, and the man who convinced Pierre-Emmanuel Taittinger to plant in England. “Vineyards are being planted in Holland, Sweden — everyone is having to adapt to the challenges.”

“It is not good news for any of us, but English sparkling wine is on the right side of climate change,” McGrath adds. “If we knew we were heading for another ice age, you wouldn’t have seen the same level of investment.”

England was for most of its history a prolific wine-consuming, rather than a winemaking nation.

Since Roman times, Brits have tried to grow vines, but England’s damp and chilly climate made it virtually impossible. Finally, after the second world war, researchers found that Kent’s climate and landscape could sustain the growth of cool grape varieties like Seyval Blanc and Müller-Thurgau.

England’s first commercial vineyard, opened in the 1950s, was Hambledon. But the road to success was long and difficult — at one point the estate shrank down to just 4 acres. In 1999 it was acquired by equity analyst Ian Kellett, who transformed it into the leading sparkling wine producer it is today.

Despite its award winning output, Hambledon was unable to keep up with the costs of its expansion plans, leaving it vulnerable to a takeover. Last year, wine merchant Berry Bros & Rudd and Symington Family Estates, a port and wine producer based in the Douro Valley, Portugal acquired the business with a £22.3mn takeover bid.

The history of Hambledon shows how new entrants into English wine have evolved over the course of half a century; initially researchers and hobbyists, then wealthy investors and retirees with spare capital, and now strategic trade buyers.

“We see a big business opportunity,” says Rob Symington, director at Symington Family Estates. Sparkling wines are growing at a faster rate globally than still wines, and with only 7 per cent penetration in the domestic market, there was plenty of room for growth, he said.

Symington also spotted an opportunity to buy before English land suitable for growing became less affordable. Land under vine in England is currently valued at around £123,500 per ha, up from £99,000 per ha last year, according to Strutt and Parker. But this pales in comparison to the €1mn average price per hectare in Champagne.

“In five to 10 years time it would cost us a lot more than it did today. It is higher risk but higher return over time,” says Symington. “I’m pretty sure we won’t be the last wine producer from outside the UK to come in.”

The same goes for local big names. Emma Fox, chief executive of Berry Bros and Rudd, says that although their immediate priority is developing Hambledon she would “never say never” to buying more vineyards in England.

Land values are likely to shoot higher as the industry begins to seek Protected Designation of Origin for winemaking counties as they have in the Napa Valley and the Champagne region. Mark Driver, a former hedge fund manager who set up Rathfinny Wine Estate, and other wineries in Sussex successfully applied for the registration of “Sussex” as a PDO. Other counties could soon follow suit.

Yet for all its success and potential, the English wine industry is likely to remain a small sliver of the overall UK economy.

Regardless of the growing investment and land under vine, the industry is still intensely fragmented, made up for the most part of small and medium sized wineries, generating returns that are unlikely to tempt serious investors. Producers that own 100 ha or more are rare, making up just 1 per cent of the industry.

It is notoriously difficult to turn a profit from wine businesses, with high operational costs exacerbated by inflation and high borrowing costs. Owners tend to get involved because of their passion for winemaking, not because wine is the most lucrative business.

As a result, selling can be a “very emotional and painful decision,” says Mansel Lewis. “Not everyone sells because they want to. And it’s not a perfect market where, if supply and demand are equal, there’s a deal. You have to ensure they are the right partners for one another.”

Only a handful of English producers are profitable, with several major producers loss-making in the past few years. Chapel Down’s operating profit rose 81 per cent to £2.4mn in 2023, from £1.3mn in 2022. By contrast Gusbourne made an operating loss of £1.3mn in 2023.

“Its difficult to make a decent return on investment in wine, that’s why there are so many family companies in it,” says Symington. “An investor would look at it and say, ‘The numbers don’t stack up.’”

For now the industry is focused on boosting awareness in the domestic market, which currently makes up 93 per cent of total sales.

One strategy is to push wine tourism, in the hope that consumers will make a habit of buying local wines at the cellar door, where producers can make far higher margins than if they sell through retailers or bars and restaurants.

Many UK consumers balk at the price of English sparkling wine, particularly when faced with a raft of cheaper, mass-produced sparkling options from Europe on supermarket shelves.

English wine sales have flattened out in the past few years, leading to concerns about overproduction. In 2022, the sector sold 8mn bottles, with the top 25 producers accounting for 83 per cent of sales, compared to 9.3mn in 2021 and 7.1mn in 2020.

Supermarkets, however, tell the FT that sales have picked up dramatically in the past year. Aldi says it has seen a 60 per cent surge in sales of its English wine range in the year to June, while M&S says sales were up 35 per cent over the same period, with English sparkling wine currently outselling cava.

“There’s a lot of rapid growth within the industry, which is fine, we aren’t at the overproduction stage yet,” says Charlie Holland. “But there are inevitably growing pains with a young industry, so we need to work collaboratively.”

For many large overseas investors, however, the English wine industry might be best considered a safe haven against prevailing climactic trends.

As well as its site in Crouch Valley, the California winemaker JFW has been buying vineyards in the northern US states of Washington and Oregon, and over the border in Vancouver, as a hedge against possible falling yields at its vineyards closer to the equator.

“[JFW are] a family business, thinking about the future, climate change and a warming planet,” says Holland. “For them to be a generational business and sustainable, that’s what they need to do.”

Additional reporting by Laura Onita