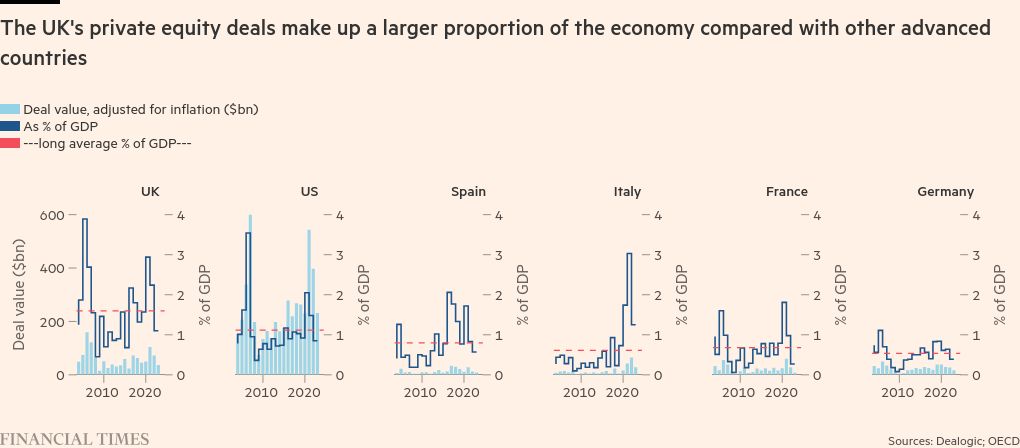

Nowhere in the world have private equity firms found a more welcoming playground than in the UK: the volumes of buyouts have over the past two decades weighed more in the overall economy than in any other advanced market, including the US, where the industry was born, data shows.

Private equity firms have snapped up high street names from grocers Asda and Morrisons to sandwich chain Pret A Manger, and invested in sectors ranging from insurance to nursing homes and infrastructure.

Now their record, and relatively lower taxation, are once again coming under heightened scrutiny ahead of next week’s elections. The Labour party, which is leading in the polls, wants to increase taxes on performance fees that fund managers receive from asset sales, prompting worries these dealmakers may be tempted to relocate elsewhere.

How fast did the private equity industry grow?

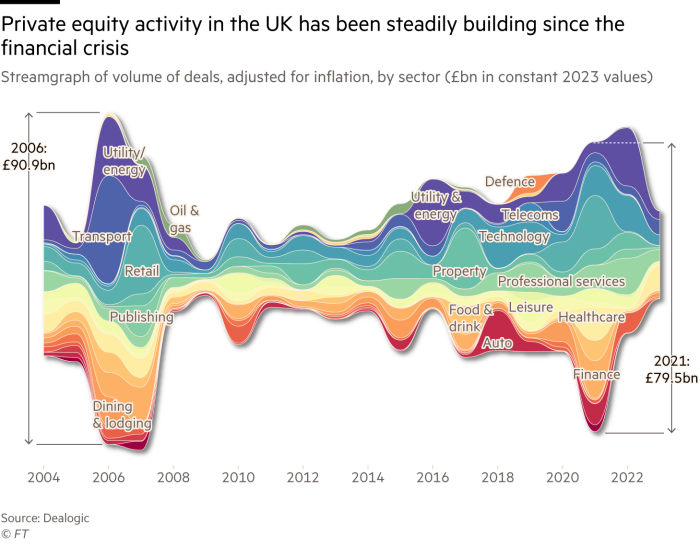

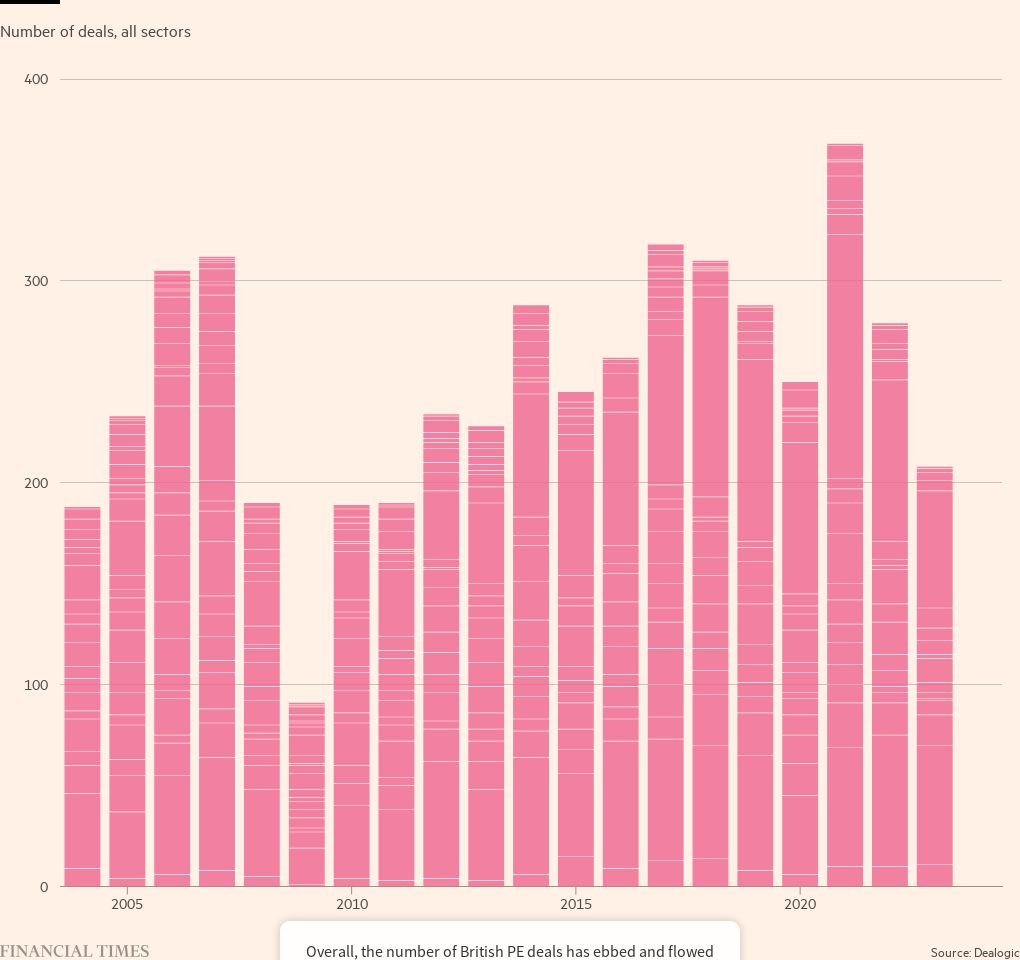

UK-based private equity groups followed in the footsteps of US buyout pioneers, including KKR, in the 1990s, raising funds from pension and sovereign wealth funds to target UK and European companies. Aggregate value of private equity transactions peaked at £91bn in 2006.

The global financial crisis around 2007 and 2008 cooled activity, with private equity investors shifting their focus away from sectors such as transportation to technology and professional services.

But over the past two decades, deals have made up a greater share of the economy than in the US or other European markets, according to data from Dealogic, with London becoming a European hub. Over time, thousands of investors and associated service providers also chose the City of London as their base.

What are the largest private equity firms in the UK?

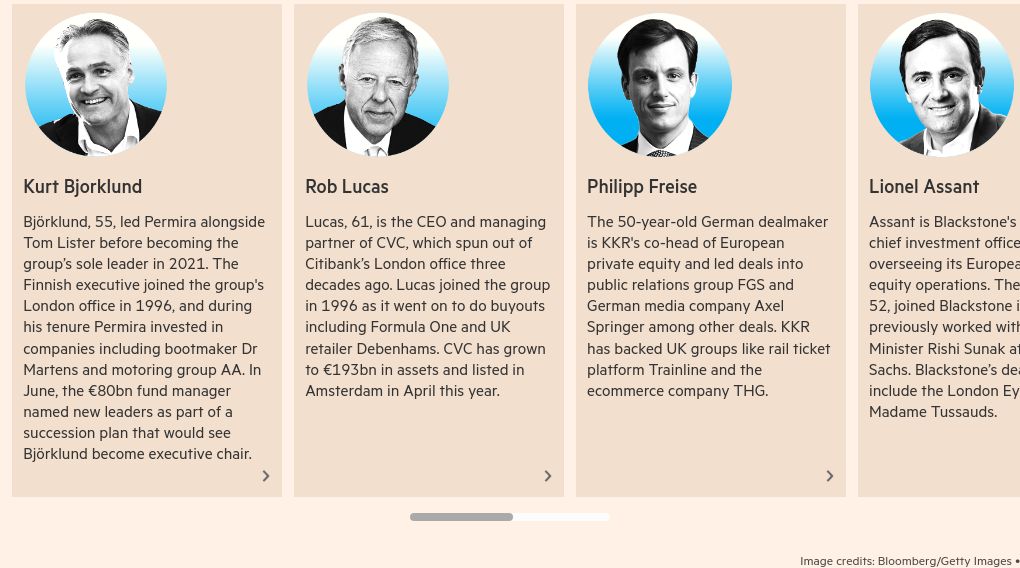

Top buyout groups such as CVC, Permira, Cinven and Apax are based or have their largest office in London, while US groups such as KKR, Blackstone, Apollo and Clayton, Dubilier & Rice have established their main European outposts in the British capital. These tend to fund the largest deals with some of their biggest investors, including sovereign wealth funds, such as GIC, and pension funds, such as the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board.

Blackstone, the world’s largest alternatives investor by assets under management, has been the most active, including through its real estate arm. The group’s senior European private equity executive Lionel Assant and its recently knighted founder Stephen Schwarzman have a close relationship with Prime Minister Rishi Sunak.

Which sectors have buyout groups targeted?

While the earlier years of the industry were shaped by massive buyouts in sectors such as consumer and retail, dealmakers have shifted their focus lately towards real estate and healthcare.

Technology, particularly software with its reliable recurring sales, has also become favoured by investors for its resilience and growth.

However, the large transactions in other sectors have shaped the industry’s public perception. The woes facing Thames Water, the UK’s largest water utility that was previously owned by Macquarie, and previous crises at private equity-owned care homes, have been among the episodes that darkened PE’s reputation. In 2007, private equity bosses were hauled in front of parliamentary committees where they admitted to mistakes in their handling of deals.

Here are the top private equity deals in the UK over the past 20 years:

Who are the men in charge?

The leadership of the UK’s top private equity firms are a male-dominated and international group. While the industry is relatively small in terms of the number of people it employs — law firm Macfarlanes estimated that only 2,550 people received carried interest — it is a valuable source of fees for law firms, banks and consulting firms. The number of workers affected by private equity stretches into the millions once staffers at portfolio companies are included.

“There have been real benefits to having such a large presence for the industry here,” argues Michael Moore, head of the industry’s lobby group, British Private Equity and Venture Capital Association.

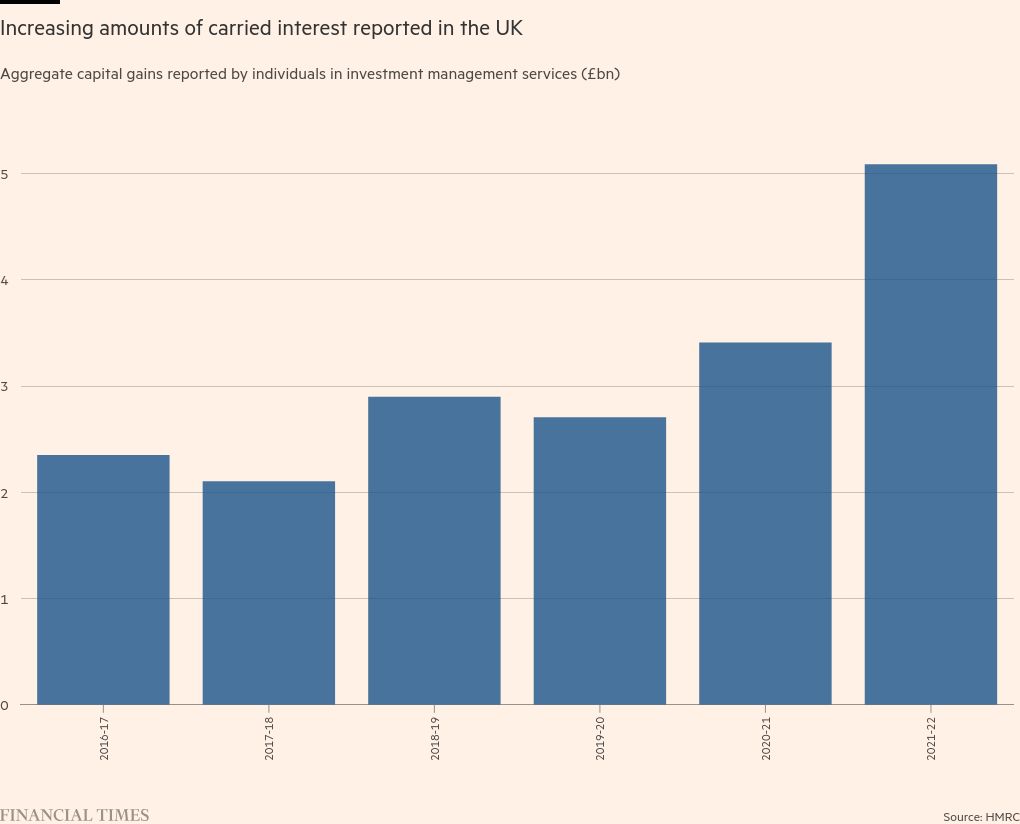

How much ‘carry’ have private equity firms received?

Carried interest, which is typically 20 per cent of the gains that buyout groups generate from deals, has boomed, fuelled by a long period of cheap debt financing. During the pandemic years of 2021 to 2022, spurred by low interest rates, massive state help and a flurry of transactions, UK buyout executives saw their incentive fees surge past £5bn.

Labour’s plan to raise taxes on these fees and go further than a planned Tory crackdown on the favourable “non-dom” tax regime for expatriates has unsettled the industry. Labour expects to raise a modest £565mn a year by closing the carry “loophole”.

The BVCA has warned the Labour pledge to tax carried interest as ordinary income — at the marginal rate of 45 per cent — from lower-taxed capital gains, risked pushing dealmakers abroad.

Not all industry participants share this alarmist assessment. Ludovic Phalippou, a professor at Oxford’s Saïd School of Business, who has documented the rapid rise of private equity billionaires, says that while a few executives might leave to reduce their tax burden, funds would continue to be invested in the UK.

There are also signs shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves would soften the blow. She suggested earlier this month that buyout executives who invest in their funds would continue to enjoy favourable tax treatment — aligning the UK with France or Italy.

The industry welcomed the comment as “encouraging”. But the debate comes on top of fresh challenges to the private equity business model, which must continue to justify its hefty fees by delivering market-beating returns.

This is getting more difficult with higher interest rates, because it limits the ability to fund buyouts with debt. A slowdown in deals and listings, due to political uncertainty in Europe, has also made it harder to return capital to investors.

While the past two decades have been lucrative for these firms, “going forward, it’s not clear at all that they can replicate that”, Phalippou says.

Data visualisation and analysis by Patrick Mathurin and Alan Smith