Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

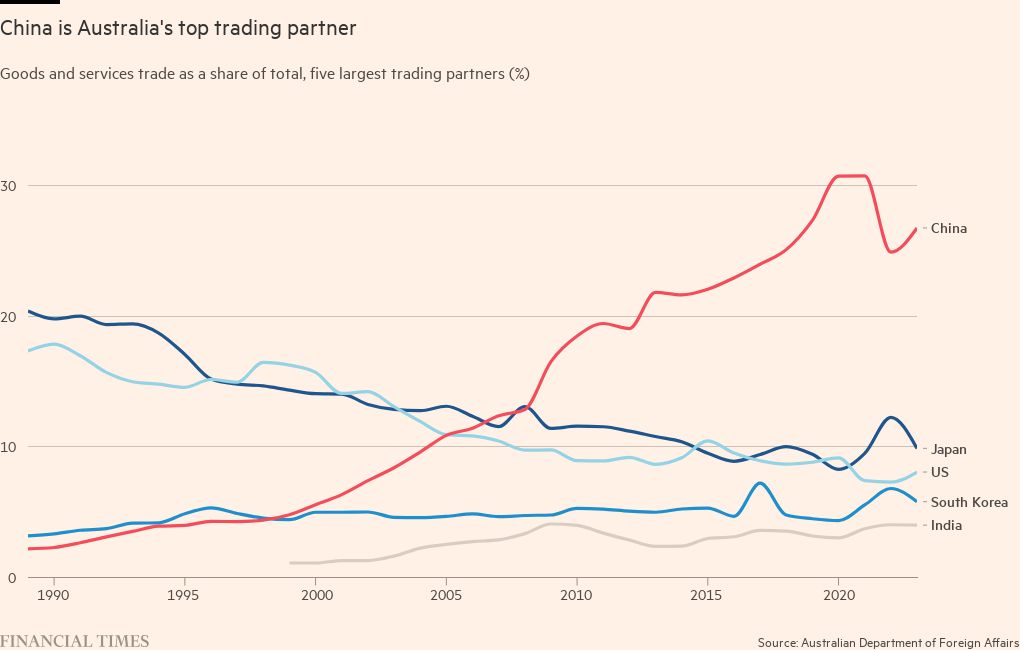

Australia’s trade with China has jumped in the past year to record levels, as relations between the two countries recovered from a damaging dispute sparked by the Covid-19 pandemic despite wider security tensions in the region.

Total trade with China reached A$219bn (US$145bn) in 2023, the highest-ever level and up from A$168bn in 2019, the last year before the outbreak of the pandemic and imposition of Chinese tariffs and sanctions, according to official data from the Australian government.

The importance of the trade ties was on clear display this weekend, as Chinese premier Li Qiang made a four-day visit that included Australia’s mining and winemaking regions, underscoring the importance of the country’s commodities to the Chinese economy even as Canberra has embraced closer security ties with Washington.

The trip — the first by a senior Chinese leader since former premier Li Keqiang’s visit in 2017 — followed high-level meetings including visits by Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and foreign minister Penny Wong, as Beijing and Canberra have sought to mend frayed ties in a lucrative trade relationship.

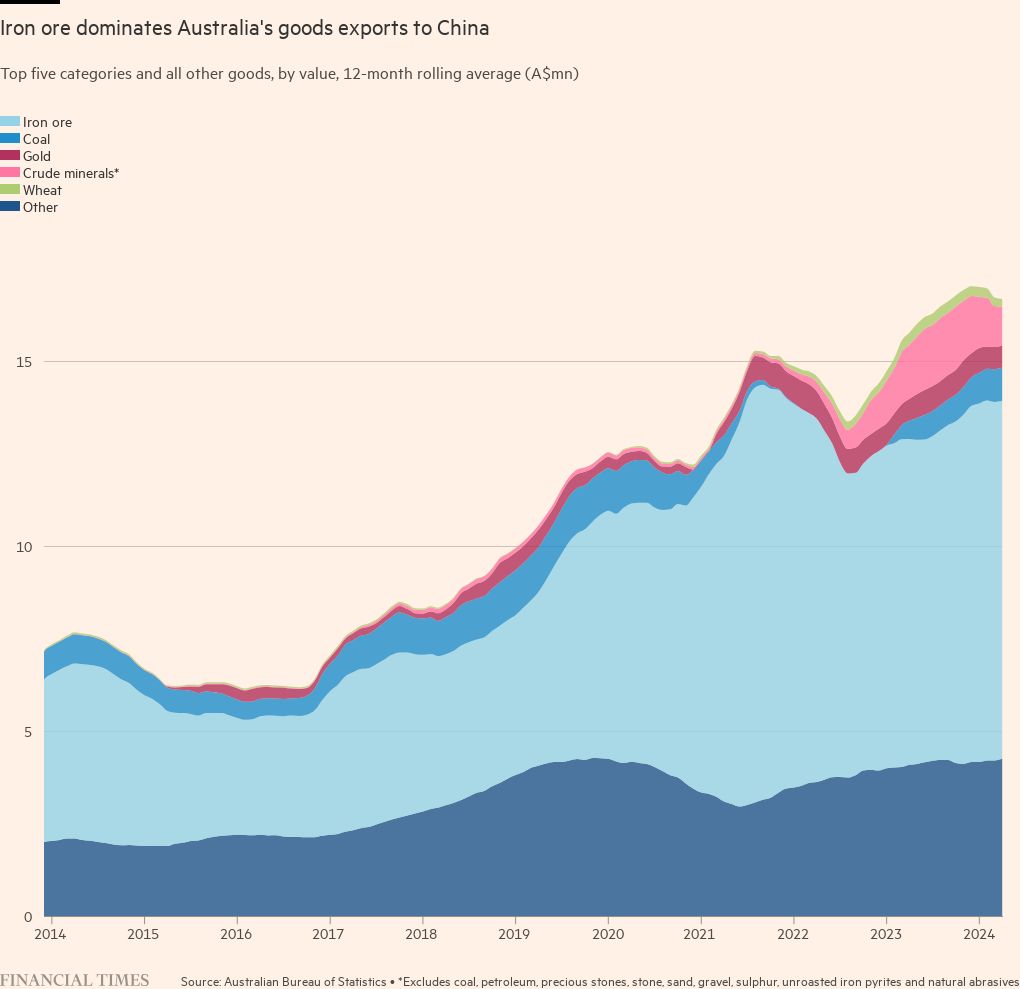

The recovery in trade value has been driven in particular by rising prices of iron ore — Australia’s most important export — and a rebound in services after travel and tourism dropped off during the pandemic and relations soured.

“The economic relationship is very strong and growing in spite of all the noise,” said Hans Hendrischke, professor of Chinese business and management at the University of Sydney.

Diplomatic relations had been their most fraught point in decades after Beijing in 2020 enacted punitive tariffs, sanctions and informal bans on about A$20bn of Australian goods including coal, barley and wine, and detained Australian citizens.

China introduced the tariffs in response to then-prime minister Scott Morrison’s call for a public inquiry into the origins of Covid-19, and after Australia became the first country in the world to ban Chinese vendors including Huawei from its 5G telecoms network.

Albanese’s election in 2022 proved to be a catalyst for a thaw in tensions, but Australia had managed to weather the sanctions thanks to a surge in global commodity prices during the pandemic and diversification into other markets.

Meanwhile, Australian iron ore and lithium, a critical ingredient in electric vehicle batteries and core to Beijing’s new technology drive, continued to flow to China, preserving Australia’s economic resilience.

Lobsters are the only residual export still subject to the 2020 trade restrictions. However, Don Farrell, Australia’s trade minister, said last week that he was “very confident” that barriers to the crustacean would soon be lifted.

Farrell added that A$86mn of wine was shipped to China in April, the month after tariffs were lifted, and that he was optimistic trade would make a “full recovery”. Australia exported A$1.2bn of wine a year to China before the tariffs were imposed.

Li’s visit followed a three-day trip to New Zealand, during which he announced visa-free travel and solicited support for China’s admission to the CPTPP trade pact.

The Chinese premier’s Australia leg included stopovers in Adelaide — where the resumption of trade will be welcomed by winemakers hit by a supply glut — and Perth, the mining and minerals hub, where Li and Albanese will hold a business roundtable with BHP, Rio Tinto, Fortescue and Chinese miners that operate in Australia.

Li will also visit Fortescue’s green energy research facility in a Perth suburb and a lithium hydroxide refinery — the largest outside China — run by China’s Tianqi and Australia’s IGO, which has struggled to increase output. Its headquarters is built in the style of a Chinese water garden, with giant stone lions and Chinese friezes.

Hendrischke said that the trip to the lithium facility was a “signal of pressure” to Australian authorities over its critical mineral ambitions. Australia this month ordered China-linked funds to cut their investments in a rare-earths miner, citing “national interest”.

“Whether Australia wants to or not, it will have to co-operate with China on these minerals,” he said. “The US will push against that, but they don’t have the technology.”

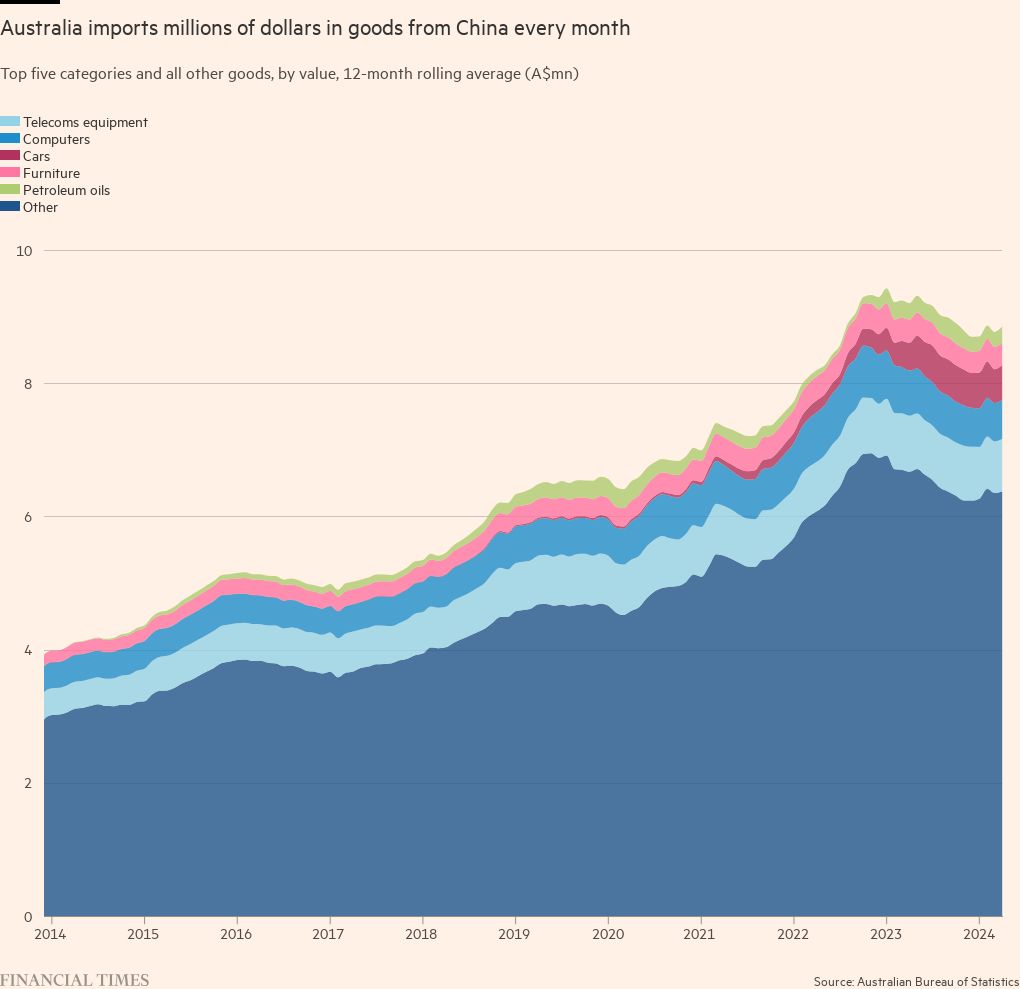

Some observers questioned Canberra’s strategy of not just restoring but expanding trade with Beijing at a time when security rifts in the Indo-Pacific region are deepening, and as Australia seeks to carve out a supply chain of critical mineral processing to compete with China.

In November, Australia said a Chinese frigate’s use of sonar injured an Australian naval diver, while last month, Albanese objected after a Chinese fighter jet fired flares in the path of an Australian naval helicopter over international waters.

Australia has also pushed ahead with the Aukus security alliance with the US and UK and dramatically increased defence spending in response to China’s increasingly aggressive behaviour in the region.

One former government adviser said that Canberra’s approach was suffering from “cakeism”.

“We want a full-throated military deterrent to China but desperately still want access to that market for our iron ore and wine,” the adviser said.

“Stabilisation of the relationship was needed, but what does stabilisation mean with China? This is going to get harder over time.”