Exxon leads industry fight against UN plans to limit plastic

Exxon is leading a fightback by the petrochemicals industry against plans to cap the production of plastics ahead of UN talks on the first legally binding treaty aimed at cutting pollution.

Karen McKee, the head of product solutions for ExxonMobil, one of the world’s largest producers of plastic, told the Financial Times: “The issue is pollution. The issue is not plastic.”

“A limit on plastic production will not serve us in terms of pollution and the environment.”

McKee said alternatives to plastic packaging could have a higher emissions footprint. Exxon produced 11.2mn metric tonnes of polyethylene last year and operates a chemical recycling plant for plastic in Baytown, Texas.

The statement from McKee, who is also the chair of the International Council of Chemical Associations, which represents the largest petrochemical companies, drew an angry response from environmental campaigners and other business groups.

“The [oil and gas] sector are looking at plastic as being the next opportunity for the industry . . . That’s really problematic for the rest of us,” said John Duncan, co-lead for the Business Coalition for a Global Plastics Treaty, a group of more than 300 companies including Walmart, PepsiCo, and L’Oréal which support a reduction in plastic production.

“If we are living up to the projected increases that these companies are investing in, the future is even more catastrophic.”

More than 4,000 country delegates and observers will gather in Ottawa, Canada on April 23 in the penultimate round of UN negotiations to broker a deal likened to the 2015 Paris climate agreement for plastics. Disagreements over how the 400mn tonnes of annual plastic waste should be managed have stalled negotiations.

The plastics industry and large oil-producing countries including Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Iran have pushed for a global treaty that focuses on recycling over production cuts.

Last week, an Oxford Economics report sponsored by the ICCA said a cap on plastics production would push up prices and burden low-income households in addition to potentially increasing emissions.

Plastics are relatively light and require less energy to manufacture and transport than some alternative applications, according to the report.

“Recycling is not the only solution, it’s not a gold ticket to environmental improvement, but we think we can improve what we know is working and then move on from there,” said Betsy Bowers, spokesperson for the Global EPS Sustainability Alliance, representing the expanded polystyrene industry.

She added that a curb on production was not a “good choice” given the lack of alternatives.

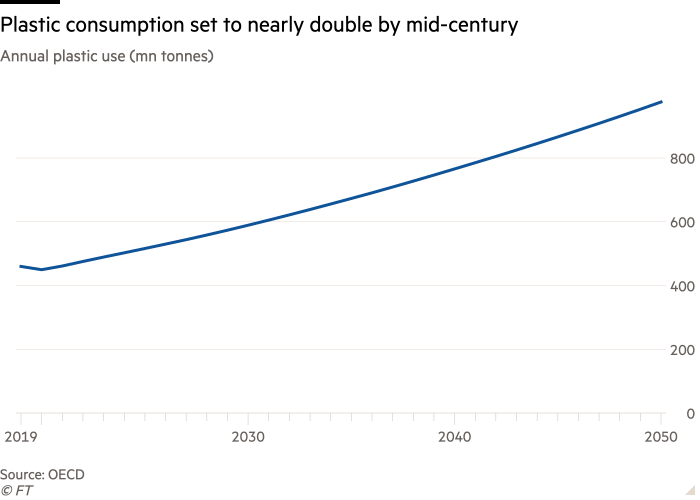

Global demand for plastics, which makes up 50 per cent of petrochemical demand, is expected to nearly double by mid-century, according to S&P Global Commodity Insights. The International Energy Agency expects petrochemicals to be the “single largest contributor” to oil demand growth in the next five years, as the rapid deployment of renewables and the move to more fuel efficient and electric vehicles curbs oil demand in other sectors.

“It’s one of the industries where we’re seeing oil and gas companies focus because they know demand for plastics is only expected to grow in the long term,” said Kirti Vasta, a research analyst at BloombergNEF.

Plastic production made up 5 per cent of global emissions in 2019 and is expected to double by mid-century, posing a threat to global efforts to keep warming to 1.5C, according to a new report from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. The report’s authors acknowledge that some alternative materials to plastic risk increasing emissions, but argue that eliminating non-essential use of plastics can lead to a reduction in emissions.

Meanwhile, countries including members of the EU and a handful of oil producers like the United Arab Emirates, along with environmentalists, argue that without binding cuts to plastics production, recycling is an insufficient and uneconomical solution. Roughly 10 per cent of all plastic is recycled, according to the OECD, which estimates investment in recycling must reach $1tn by 2040, up from under $20bn today.

“There’s a growing and increasingly overwhelming recognition that recycling alone is never going to address the plastic crisis,” said Carroll Muffett, chief executive of the Center for International Environmental Law, which found a 36 per cent increase in attendance from fossil fuel and industry lobbyists in the last round of negotiations in November.

Inger Andersen, head of the UN Environmental Programme, which is leading the talks, said capping the production of plastics may “legislate ourselves into a corner”, and pushed for provisions to address single-use, shortlived plastics.

“Whether the treaty includes plastic production cuts is not just a policy debate. It’s a matter of survival,” said Jorge Emmanuel, an adjunct professor at Silliman University, citing recent natural disasters including heatwaves, flooding and typhoons in the Philippines.

Additional reporting from Madeleine Speed in London